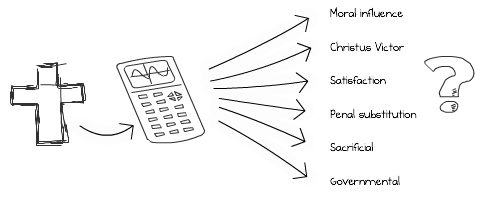

At the simplest level what we mean by “atonement” is that Jesus died for my sins in order to reconcile me to a holy God. But when the church attempts to explain how Jesus’ death on the cross does this, we quickly find ourselves entangled in a number of competing theories: the moral influence theory (popular with liberals), the Christus Victor theory (currently popular with emerging types), Anselm’s satisfaction theory (popular with Anselm), the notorious penal substitution theory (popular with the neo-Reformed), the sacrificial theory (popular with the writers of the New Testament, but see below), the governmental theory of Hugo Grotius, and no doubt many others.

What this whole approach rather suggests is that in our minds metaphysics works in much the same way as physics does: we assume that the hidden workings of an event or process require a single theoretical explanation.

Leon Morris’ comments on the sacrificial theory are revealing in this respect:

it is an explanation that does not explain. The moral view or penal substitution may be right or wrong, but at least they are intelligible. But how does sacrifice save? The answer is not obvious.

But this obsessive need we have to provide a rational explanation for the atonement—whether right or wrong!—is more of a hindrance than a help when it comes to understanding what’s actually going on in the New Testament. What we have in these writings is not a body of disorderly empirical data regarding Jesus’ death that must be organized and rationalized into a coherent explanatory theory or model. There is no “must” about it—except for the imperative of Western culture to give a scientific or quasi-scientific account of everything. What we have in the New Testament are mostly undeveloped arguments—in different contexts, for different reasons—about the significance of the historical event of Jesus’ death for Israel and its relationship to the nations.

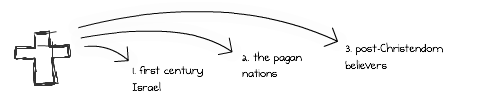

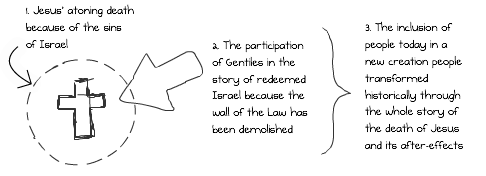

I will argue here that the most important distinction to be made as we consider these various arguments is between (1) the significance of Jesus’ death for Israel and (2) its significance for the pagan nations within the eschatological narrative presupposed by the New Testament. This leaves open the possibility (3) that our own relation to the death of Jesus may need to be framed in different terms again.

The redemption of Israel

We begin with what is probably the clearest statement that the Jesus of the Gospels makes about the significance of his death. “Ransom” terminology in the Old Testament derives primarily from a legal setting. A “ransom” (lutron) is paid for the recovery or preservation of property or life (eg. Ex. 21:30 LXX). But the verb (lutroō) is widely used in a metaphorical sense for the redemption of Israel from the consequences of divine judgment (eg. Is. 51:11; 52:3; 62:12; 63:4, 9 LXX). When Jesus says that “the Son of Man came not to serve but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mk. 10:45), he means that his suffering will be the means by which Israel will be redeemed from its current “exile” or state of oppression. It is idle and pointless to ask what exactly is paid and to whom.

The penal substitutionary view of atonement is often dismissed as a moral absurdity, if not horror; but it makes very good sense in the Jewish part of the unfolding story of the transformation of the people of God. Jesus suffered in his own body the destruction at the hands of the Romans that was to be Israel’s punishment. The New Testament makes surprisingly little overt use of Isaiah 53, but the thought is certainly there that Jesus is in some sense the servant who is wounded, crushed, and punished because of the transgressions of Israel. I have made this case also with respect to 2 Corinthians 5:14 and 5:21: in his death Jesus was made a “sin offering” for all.

Paul’s statement in Romans 3:24-25 that all are justified “through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation (hilastērion) by his blood” is in the first place an argument about the redemption of Israel. The Law charges Israel—it “speaks to those who are under the Law”—with sin so that “the whole world may be held accountable to God”. Israel, therefore, will not be justified at this time of eschatological crisis by works of the Law (3:19-20). But God has shown that he is righteous nevertheless by providing an alternative “redemption” (apolutrōsis) for Israel through faith in Jesus’ death as an event that atones for Israel’s sins. We have the same metaphor in 4 Maccabees 17:22,used with reference to the deaths of the martyrs: “And through the blood of those pious people and the propitiatory (hilastēriou) of their death, divine Providence preserved Israel, though before it had been afflicted” (NETS). All who believe in this act of redemption for all Israel will be justified on the day of God’s wrath against the oikoumenē.

The argument that Jesus “redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us” (Gal. 3:13) is also an argument about the redemption of Israel. We hear Paul speaking for the whole of humanity here, but that is an error of perspective and theological conditioning. Paul speaks on behalf of that part of Israel that is being saved by its faith in the story of Jesus, to which some Gentiles have also been attached. It is Israel, not humanity, that lives under the curse of the Law because it has not done the works of the Law. Christ took that curse upon himself, Paul argues, whenhe was hung on a tree; and one of the consequences of that redemptive act for Israel was that the blessing of Abraham was extended from Israel to the Gentiles.

The inclusion of Gentiles in redeemed Israel

Here, indeed, we have the basic structure of Paul’s soteriology: Jesus’ redemptive death for Israel, interpreted according to Jewish presuppositions, had the effect of opening the door of membership of the saved community to Gentiles.

So in Ephesians 2 Paul argues that Jesus’ death has led to the inclusion of Gentiles in the covenant community. How? Not by ransoming or redeeming them, but by demolishing the “dividing wall of hostility” which up to that point had strictly excluded uncircumcised Gentiles from participation in the “commonwealth of Israel”, by “abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances” (2:15). In effect, Jesus’ death had rendered the Law irrelevant—the resurrection, and the subsequent outpouring of the Spirit, had demonstrated clearly that the coming eschatological crisis had to be faced not on the basis of Law but on the basis of concrete, resolute, obedient trust in the face of intense hostility.

We have a similar situation in Colossians 2:11-15. This predominantly Gentile community has participated in the death and resurrection and “fulness” of Jesus in relation to all powers and authorities through the concrete commitment of baptism. They have been forgiven; the record of debt against them has been cancelled, set aside; but the link with Jesus’ death is established with a simple non-theological metaphor: “nailing it to the cross” (2:14).

There is no appeal here to Jewish narratives of atonement. The cross is the means by which rulers and authorities are disarmed and put to shame. The confirmation of Jesus’ triumph over the rulers and authorities is the resurrection: he was condemned by his powerful opponents, the leaders in Jerusalem and their Roman masters, but they were ultimately shown to be powerless, unable to suppress the revolt of faith against the status quo.

Since the Colossians have been baptized into this narrative (cf. Rom. 6:3-4), it is likely that Paul also has in mind the powerlessness of local rulers and authorities, with earthly or spiritual, to suppress the witness of the community, even through violence. Similarly, in view of Jesus’ insistence that his followers must also serve (Mk. 10:43-44), arguably it is the suffering of the martyr communities which, practically speaking, brings about the ransoming of Israel.

Here we begin to see how the ideas of exemplification and imitation come into play. Christ is the first martyr. He models the radical faithfulness that the churches will have to imitate if they are to survive the coming “tribulation”. He is “the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:2).

Tell me the whole, whole story

So Jesus died for the sins of Israel and this redemption allowed for the participation of Gentiles in the people of God. This is roughly how the data is organized in the New Testament, though the boundaries are blurred a bit in places: for example, in 1 Timothy 2:6 Paul uses the very rare non-biblical word antilutron when he speaks of Jesus giving himself as a “ransom for all”.

But what about us? We are not first century Israel under the wrath of God because of the nation’s persistent rebelliousness; nor are we now in the position of the Gentiles debarred from participation in the “commonwealth of Israel” by the Law. This part of the story has worked itself out.

We still come to God as sinners, trapped in a corrupted order of things from which we are powerless to escape. We may still need to say, quite simply, that Jesus died for our sins so that we may be part of a people reconciled to the God who brought it into existence to be “new creation”. Jesus’ death has opened up to me personally the possibility of being a player in God’s new world. But the continuing dependence of the people of God on the death of Jesus needs to be construed and explained not in abstract theoretical terms but narratively, historically—and of course, biblically.

Jesus was named Jesus because He would save His people from their sins. Matt. 1:21 And also John 2:2 tells us Jesus died for the sins of the whole world.

The main thing for me is that Jesus died for me, personally. He gave Himself for me, because He loved me. He loved me before the foundation of the world, and so He sought me out, as one of His lost sheep, (John 10) and opened my heart and eyes to the truth and rescued me from death, sin, and the balck darkness my soul was bond to. Jesus brought me into His marvelous light as Peter tells us.

I also see the Word teaches that Jesus was my propitiation, and so according to Isa. 53 He was crushed by God for me. I will never be able to understand this truth. But I trust His truth.

Have a great day in the truth. Gal. 6:14

@donsands:

OK, Don, but what I am asking is how this material would read if we didn’t simply scavenge through the Bible picking out all the statements that have to do in some way with atonement and claim that they were all written for me.

Isaiah was written to Israel. Romans was written by a Jew. In any other area of literary interpretation we would not automatically assume that a text written by someone else to someone else is directly addressed to me. If I happened to come across a letter written by you to your son (just suppose) saying that you would buy him a new car for his birthday, you would be shocked if I came knocking on your door asking for my car. You would not think that just because the letter has fallen into my hands, you have become my father and I have become your son.

That’s a bad choice of illustration—I am not trying to say that God is not my Father, only that there is a context to the communication.

Isaiah 53 does not say that Jesus was crushed by God for you. It says he was crushed for Israel’s trespasses. What that statement has to do with you is rather more complicated.

I am suggesting that in reading scripture—and in constructing an understanding of Jesus’ death—we may make better sense of things if we don’t assume that it is always about us.

@Andrew Perriman:

“Isaiah 53 does not say that Jesus was crushed by God for you. It says he was crushed for Israel’s trespasses. What that statement has to do with you is rather more complicated.”

I don’t think it’s complicated at all. I love the simplicty of Christ dying for me. And this is clearly written within the Holy Word of our Lord.

I don’t see any complication here Andrew. There’s the simple and pure truth of God’s love for His elect that should cause us to have tears of great joy.

Luther says: “”Let us learn to give a true definition of Christ; let us define as Paul does: namely, that He was the Son of God, who not for any righteousness of ours, but of His own free mercy and love, offered up Himself as a sacrifice for us sinners, (Jews and Gentiles) that he might sanctify us forever……He died not to justify the righteous, but the unrighteous, and to make them friends and children of God, and inheritors of all heavenly gifts. Therefore, when I feel and confess myself to be a sinner through Adam’s transgression, why should I not say that I am made righteous through the righteousness of Christ, especially when I hear that He loved me, and gave Himself for me?” (From Gal. 2:20)

“For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.”-Paul the Jew talking to Gentiles about all of God’s beloved elect.

“For I have betrothed you to one husband, that I may present you as a chaste virgin to Christ. But I fear, lest somehow, as the serpent deceived Eve by his craftiness, so your minds may be corrupted from the simplicity that is in Christ. For if he who comes preaches another Jesus whom we have not preached, or if you receive a different spirit which you have not received, or a different gospel which you have not accepted—you may well put up with it!”-And Paul to the same gentiles, the bride of Christ.

Andrew,

Great post. I’ve been re-thinking the atonement lately. I must admit, as one who has been thoroughly affected by modernity, I attempt to understand things. The whole thought process of sacrifice doesn’t make all too much sense to me, but it seems that if the notion of sacrifice is rejected, much is lost in the New Testament.

Two things.

One thing that has helped me has been to take away the word “propitiation”; with the definition of “sacrifice to eliminate punishment” or some such, it bears no relation to the Greek word that is actually found in the text. That word, hilasterion, is properly translated as “mercy-seat”: the place where the representative of Israel, the High Priest, would come before the presence of the Lord with the offering of the life (blood) of the community as an expression of faithfulness in covenant and worship. I think this dovetails quite well with Wright’s point, and yours, Andrew: Jesus as the Representative Israelite who offers his life in covenant faithfulness to God, which the official religious leaders of his day had lost sight of at the end of a long line of unfaithful acts, for which judgment was on the way.

Two, in the Eastern church, the notion of “atonement theory” really has no place. The Cross is not explained as punishment, nor as any other of the examples listed. The idea of judgment is certainly there, and may be a conceptual link between the interpretation of those in the first century and those of later centuries; but it is not the Father judging the son in place of sinful humanity. The judgment idea, when mentioned at all, is more along the lines of Wright’s thought on sin being judged in the human body of Jesus; the judgment idea is not otherwise very prominent in the East. The Cross is more explicitly seen as three things: the identification of Christ with humanity to the point of death (that which is not assumed is not healed; the culmination of the Incarnation, if you will); Jesus’ entrance into death in order to abolish it; the public display of the enormity of God’s forgiveness of all of humanity in the face of being put to death by his creation. So the prominence of Christus Victor in the east is mostly about the Resurrection. The cross is certainly a part of it; you can’t have one without the other. But the Cross is not seen as victory, but rather as the Love and Humility of God. The victory in the scene is vastly more about the Victory of Christ’s Resurrection over Death.

Again, I can see how the first of the three horizons, the extremely Jewish one, morphed into the second, tracing it through the extrabiblical (non-Gnostic) writings of the Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr and others who were, through time and culture, removed from the intensity of the C1 Jewish experience. Not that I’ve read them exhaustively, but I see threads. Then in the fourth century, much quicker morphing into the beginnings of the third horizon, since the persecutions had ceased and Christianity had become legal. I think it was actually a time of a lot of disorientation, with a lot of leaders having been killed in the last persecutions, and the community all of a sudden losing its identity as a persecuted (though large) minority. Makes me even more in awe of the Cappadocians and the others who were dealing with the situation then.

Dana

@Dana Ames:

Dana, I really appreciate your Eastern perspective on this whole debate. I would love to hear some (progressive?) Orthodox theologians engage with the narrative-historical approach.

I have a question about this statement though:

…where the representative of Israel, the High Priest, would come before the presence of the Lord with the offering of the life (blood) of the community as an expression of faithfulness in covenant and worship.

Is this correct? This is what we have in Leviticus 16:15-16, 30-33:

Then he shall kill the goat of the sin offering that is for the people and bring its blood inside the veil and do with its blood as he did with the blood of the bull, sprinkling it over the mercy seat and in front of the mercy seat. Thus he shall make atonement for the Holy Place, because of the uncleannesses of the people of Israel and because of their transgressions, all their sins. And so he shall do for the tent of meeting, which dwells with them in the midst of their uncleannesses.

For on this day shall atonement be made for you to cleanse you. You shall be clean before the LORD from all your sins…. And the priest who is anointed and consecrated as priest in his father’s place shall make atonement, wearing the holy linen garments. He shall make atonement for the holy sanctuary, and he shall make atonement for the tent of meeting and for the altar, and he shall make atonement for the priests and for all the people of the assembly.

What this is saying, surely, is that Israel needs to be routinely cleansed of its sins through the rituals involving the killing of animals. There is nothing directly here about appeasing the wrath of God, but the larger covenant picture meant that even the routine of the Day of Atonement could not be guaranteed to safeguard the people against the destructive wrath of God. Anyway, there seems to be more involved here than the expression of faithfulness on the part of the community.

@Andrew Perriman:

“Progressive” Orthodox theologians: Well, “progressive” is not a term that is generally looked on favorably in Orthodoxy - too close to the idea of “innovation”, departure from what was handed down from the Apostles through the whole body of the Church ;) There may be some who are interacting with narrative-historical theology, but I’m not aware of them; most of the contemporary theology is being done in Greece, and translation is very slow. In the US, J. Behr and J. Breck are recognized; they teach at one of the Orthodox seminaries here. Some aspects of narrative can be found in them, but that’s not their concentration. My friend John Burnett, also Orthodox, who appreicates Wright very much and “gets” the narrative-historical thing, has a nice archive of English documents on his blog:

http://jbburnett.com/theology/theol-00.html

John also introduced me to the work of John Sailhamer, who has mostly taught at Baptist schools in the US, and is very much into how the structure of the Pentateuch helps us interpret it. In Sailhamer’s schema, the whole sacrificial system and what the priests have to do in it comes about after the golden calf episode, a rebellion led by the priests. The Lev 16 passage is specific part of what the priests have to do in general in Ex 35 - Lev 16. The bulk of the law code involving the whole people comes after the sacrificing to goat-gods, Lev 17.1-9, which was a rebellion of the whole people, not just the priests. The wider and deeper the turning of the people from simple fellowship with God, the more complex the laws became - God had to drive home the point, so to speak. But in the beginning of the wilderness wanderings, Ex 20 - 23, the law code was very simple, with no reference to sacrifices at all after 20.26. In 20.22-26 anyone could make a very simple altar for sacrifices, and there was no differentiation of sacrifices as to different types for different purposes. It’s almost like God was saying, “Ok, you want to worship me, here’s how you do it.” How it was done was like it was done everywhere else in ANE, but without idols, and that was what set Israel apart. The humungous sacrificial system came about because Israel, the People of God, was already beginning to turn away; God’s “new beginning” of humanity with Abraham, even under Moses, was going the same way as the “original beginning” with Adam.

But sprinkled throughout the OT, as time went on and things developed, were reminders from God that he really didn’t want animal sacrifices; he wanted people’s hearts, specifically expressed in worship of God and love for and just treatment of others. And looking back through the lenses of the NT, that is reiterated. As to the Day of Atonement, well, God didn’t seem to require that an animal was killed only; there was also the scapegoat, and the people’s sins were sent away on that without it being killed.

Also, I tend to look closely at the language. I know there is danger in interpreting on the basis of roots of words only, without an understanding of how prefixes, suffixes, case and syntax come into play; at the same time, there are colors and tendencies that can be seen when all the instances of the words are in view. In Hebrew, “atonement” is kaphar/kiporah, which is simply the idea of “covering”. This may be understood to be “covering” so that God’s wrath doesn’t fall on the people. But the word used in the LXX is instructive. (As you know, the LXX rather than the Masoretic text is what is used by the Orthodox.) It is ex - ilas - is/komei/ma/mos. Notice the same root as ilas-terion. The only place I can find in the LXX where it is used before Ex 30 is Gen 32.21, where Jacob is making plans for how he can, yes, avoid “the wrath of Esau”, but the sense throughout is more of restoration, of “Will Esau ‘have mercy on me’, ‘take me in’ again?” And the colors of the root, ilas, are that of “lift, bear up, carry away”, or “mercy”, or even “prefer” (which brings it close to an understanding of “cover”).

I don’t believe that God doesn’t judge. But at the same, it seems that God’s primary intention is union with humans in love and worship. Even the sacrificial system is more concerned with making people clean, in order for that union to be enabled even in the midst of rebellion.

For a good basic primer on orthodox theology, easy to navigate, also by a Seminary professor:

http://www.oca.org/OCorthfaith.asp?SID=2

Dana

The presentation is slightly soured by the dismissive heading, and comments within the post about viewpoints with which Andrew disagrees. I don’t see why there needs to be one single rational explanation of the cross, as Andrew asserts of those who have attempted to explain it in history. However, he is doing something similar in putting forward his own viewpoint. It will have to stand alongside all the others for closer scrutiny.

As a framework, Andrew’s conceptual approach provides a system within which the cross can be portrayed. Is it true to say that the redemptive and penal functions of the cross applied exlcusively to Israel, while non-Israel benefits from the consequences through the ‘concrete’ act of baptism? And if non-Israel did benefit in this way, in what sense can those benefits be obtained in any other way than by believing in what Jesus had done for them as well as Israel? This seems to me to be the main flaw in the whole argument, though rather concealed by Andrew’s skilful deployment of the texts.

For instance, in Romans 3:24-25, Andrew asserts that this “is in the first place an argument about the redemption of Israel.” Granted, but in context, it is an argument about the absence of distinction between Israel and the Gentiles in respect of sin: “For there is no distinction: for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” - verses 22-23, where “all” refers to Jew and Gentile.

As if to anticipate Andrew’s argument, that we are looking at a death of Jesus on the cross for Jews only, Paul asks: “Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, since God is one—who will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through faith.” What is this faith? Again, as if to anticipate Andrew’s position, Paul looks to the central defining figure of Jewish identity, to whom righteousness was credited through faith in “the gospel announced in advance” (Galatians 3:8), Abraham the gentile, and says: “But the words “it was counted to him” were not written for his sake alone, but for ours also. It will be counted to us who believe in him who raised from the dead Jesus our Lord, who was delivered up for our trespasses and raised for our justification.” - Romans 4:23-25.

It is impossible to believe that Paul’s inclusive 1st person plural -“ours”, “us”, “our”, “our”, distinguishes Jew from Gentile, since the whole thrust of his argument here is about the inclusion of the Gentiles in the benefits obtained by the death of Jesus for Israel in her story. Those benefits were obtained by the death of Jesus on the cross - “delivered up for our trespasses”, and his resurrection - “raised for our justification.” Where is the distinction here between a Jesus who died for Israel and a Jesus who died for us?

On the basis of straightforward exegesis of this part of Romans, Andrew’s argument does not hold. But there is a wider picture, which as Andrew has pointed out before, is to do with the hermeneutical framework through which we interpret things. Andrew is pursuing an interesting, though to my mind misguided interpretation of the biblical story which largely limits it to a fulfilment through apoclayptic judgement on Jerusalem and Rome. There is a different framework through which to interpret the biblical story, which to my mind works equally well, in fact better, on the basis of a a narrative reading, in which Israel’s primary role is as the elect servant of the nations, whose destiny was to bring about the fulfilment of the promises to Abraham of blessing to all nations. In this story, Israel is always the arena for God’s actions, constantly on display for the nations to witness, in which Israel is a proxy for the nations in their sins as much as a proxy for their blessing.

There are problems with this interpretation, which Andrew has pointed out, and I don’t need to go into here. In the long run though, I think there are fewer problems with this interpetation than there are with Andrew’s, some of which I have pointed out. And Andrew, I’m speaking of you in the third person not to speak over your head to others, but to direct the thrust of my criticisms away from you personally, and towards the arguments themselves. I am, I hope, still on speaking terms with you.

@peter wilkinson:

Peter,

How does Jesus as Messiah fit into your schema where “Israel is always the arena for God’s actions”; particularly since so much of the NT was written for a gentile audience?

How, exactly, can there could be a “non-biblical” word…in the Bible? (1 Tim 2:6) :)

And why is a third category (post-Christendom believers) necessary in your construction? Couldn’t people today fall in the same two “New Testament” categories of Jew and Gentiles/Greeks? Isn’t that the point of unifying agency of “faith”? Atonement is made by Christ and that atonement is effected, not by works of the Law, but by the faith of Jew and Gentile alike (i.e. God “will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through faith” [Rom 3:30]). Isn’t this the mystery that Paul refers to in Ephesians 3:6? Isn’t salvation by grace through faith the same for both Jew and Gentile alike?

The atonement of Romans 3 is surely not only for the sins Israel but for Jews and Gentiles together. Isn’t that part of the whole argumentation from the very beginning of the letter until that point? This is evident in Rom 1:16-17 that all humanity (Jews and Gentiles) are in view. The sins and unrighteousness of the Gentiles is in view in Rom 1:18-32 and the sins of Israel (or moralists and Jews) in Rom 2:1—3:8. The argument climaxes with all humanity as guilty of sin (Rom 3:9-20). To suggest that only Israel was under the wrath of God misses the point of Ephesians 2, where it is Gentles who are described as “were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind… (Eph 2:3). So, I think it is an error to claim that Rom 3:24-25 (or vv. 21-31 for that matter) only has the redemption of Israel in view.

The “dividing wall of hostility” isn’t the Law but the barrier between Jew and Gentile (perhaps picturing the soreq that separated the Temple courts from the court of the Gentiles). Additionally, the claim that Jesus’ death “rendered the Law irrelevant” does not square with Romans 3:31.

The argumentation of the New Testament writers sufficiently covers all humanity - indeed, what persons would be excluded from either category of Jew or Gentile? There seems to be no reason why it is necessary to create additional views of atonement for post-Christendom believers.

@Aaron:

Aaron, thanks for the thoughtful critique.

How, exactly, can there could be a “non-biblical” word…in the Bible?

Well, yes, what I meant was that it’s not found in the Greek Old Testament, though it does occur in a variant reading of Psalm 48:9 LXX.

And why is a third category (post-Christendom believers) necessary in your construction? Couldn’t people today fall in the same two “New Testament” categories of Jew and Gentiles/Greeks?

What I wanted to highlight here are two thoughts. First, it is not now the Law that keeps people from becoming part of the people of God. There are no formal barriers to membership. Of course, historically Paul’s argument in Ephesians 2 still holds true: we Gentiles may enter the the community only because, as I would put it, Jesus died for the sins of Israel and only by faith; but in practice there are quite different controversies to address.

Secondly, I think that there is a particular prophetic thrust to the inclusion of Gentiles in the commonwealth of Israel in the New Testament, which is that it represented God’s assertion of sovereignty over the pagan world. The outcome of that prophetic thrust was Christendom—the concrete social embodiment of the victory of Christ over the gods of the nations. But since the Christendom paradigm has more or less collapsed, I think it is worth asking what now the prophetic thrust of inclusion in the people of God would be. It seems to me that having moved beyond both the atonement for Israel and the confrontation with classical paganism, we are in a position broadly to bring out the cosmic and new-creational significance of Jesus’ death. This does not make the narrative of atonement and of the initial inclusion of Gentiles any less important, but it does allow us to interpret our own circumstances more precisely. Evangelicalism’s one-size-fits-all model of salvation fails to address the contingencies of history.

The detailed argument about Romans is presented here. I appreciate that it’s not an easy one to follow. It’s set out at greater length in The Future of the People of God.

Briefly, I don’t think that Paul’s argument in Romans 1-3 is simply that Jews and Gentiles are in exactly the same situation. What we have to consider is why he has to make that case. Why does he differentiate at all between Jew and Greek? Why does he take up so much space specifically to argue that God is justified in inflicting wrath on the Jews?

The Greek-Roman world faces wrath—that is, it faces divine judgment, much as the Egyptians, Assyrians and Babylonians before had been subjected to divine judgment. That, in my view, provides the premise for the salvation of Gentiles. They are subject to an impending wrath, as you point out. But if God is to judge the pagan world, he must also judge Israel, because Israel should have embodied the knowledge and truth of the Law in the world (Rom. 2:20).

The reason it failed to do so is that the Jews were just as much enslaved to sin as the rest of humanity. But unlike the rest of humanity, the Jews were a chosen people, they were heirs to the promises made to Abraham, they had a covenant relationship with God, they were the ones who would inherit when God finally judged the nations. So their survival and effectiveness as a people become critical issues. I think that this is where the hilastērion comes in. Jesus atoned for the sins of this chosen people through his death so that something worthwhile would survive the coming wrath of God against the Jew.

I would also stress the point that justification and atonement are not the same thing in Paul’s argument. Both the Jew and the Greek will be justified by faith, but I think the argument goes like this: i) God put Jesus forward as an atonement for the sins of Israel; ii) anyone, whether Jew or Greek, who believes this is indeed the only basis for the future survival and viability of the people of God, will iii) be justified when judgment comes.

So, I think it is an error to claim that Rom 3:24-25 (or vv. 21-31 for that matter) only has the redemption of Israel in view.

No, my point is that the specific argument about the hilastērion relates to Israel. This does not mean that we cannot talk about the “redemption”—a much more general word—of Gentiles in other terms.

The “dividing wall of hostility” isn’t the Law but the barrier between Jew and Gentile (perhaps picturing the soreq that separated the Temple courts from the court of the Gentiles).

Why isn’t the soreq rather a picture of the dividing force of the Law? Paul says that Jesus broke down this wall “by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances” (Eph. 2:15); and the way of righteousness established through Jesus’ death is said to have been “apart from the Law” (Rom. 3:21). Paul may only mean that the Law has been abolished as a condition for the participation of Gentiles in the people of God—that would allow Romans 3:31 to stand as it is, though Paul may at this point mean that they uphold the Law insomuch as it now pronounces judgment on rebellious Israel.

Hey Andrew, been reading your blog for a few months now and really profiting from it. Thanks for your thoughts.

Could you explain more how Israel being judged for sin makes the whole oikoumene accountable to God? I get that Israel is under the Law, not everyone, and I get that God is going to judge the pagan nations, but I am missing the link. Besides, it says Jew and Gentile are under sin because of the following quotations, then proceeds to distinguish them again?

Also, I was more or less convinced about Gal 3:13 saying Israel is under the curse by reading Tom Wright but I still get hung up by all the personal pronouns. “cursed is everyone”, “no one may be justified by the Law”, “the righteous one lives by faith”. And universal sinfulness is a pervasive thought elsewhere in Paul. Thoughts?

–jacob

@jacob z:

Could you explain more how Israel being judged for sin makes the whole oikoumene accountable to God?

Your question gets it somewhat back-to-front, I think. It’s not that the judgment of Israel makes the oikoumenē accountable. Rather, if Israel’s God is to judge the nations, he must first hold his own people accountable. This seems to be the argument of Romans 3:5-6: God is not unrighteous to inflict wrath upon the Jews because he could not otherwise judge the world. What underlies this is the fact that it is the people which embodies the presence and truth and rightness of God in the midst of the nations—they provide a benchmark against which the nations are to be judged.

…I still get hung up by all the personal pronouns. “cursed is everyone”, “no one may be justified by the Law”, “the righteous one lives by faith”.

Doesn’t Galatians 3:10 set the boundaries of the argument: “all who rely on works of the law are under a curse”? It is specifically Israel that relies on works of the Law—and Gentiles who are persuaded that they cannot be proper “Christians” without being circumcised, etc. When Paul says, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law” (3:13), he means Christ redeemed us Jews who now have no fear of condemnation, who no longer fear the coming wrath—and perhaps those Gentiles who have been incorporated into this redeemed remnant through their belief in Jesus. After all, the early Gentile converts must have been aware of the fact that they were associating themselves with an essentially Jewish religious movement.

Does that make sense? Thanks for the questions, by the way.

Hi Andrew, my first read of this post, but I wanted to say how fascinating I found it! I am still trying to get my head around the detail, but already it has given me the clearest insight into how the narrative historical approach, as you see it, really plays out.

I can’t wait for the book to arrive - come on Amazon!! (Should’ve got the kindle!)

“It is not those who hear the law who are righteous in God’s sight, but it is those who obey the law who will be declared righteous.” Rom. 2:13 The law Paul is referencing is a law that has been added by Jesus’ crucifixion.

Respectfully, may I suggest that the execution-sacrifice of Ye’shua was first & foremost the final atonement, ie what his death brought to an end was: sacrificing to put right some act of unrighteousness. Atonment rather than redemption.

@apCaradog:

The question I have here is what do you mean by “first & foremost”? From what point of view? From the perspective of the first proclaimers of Jesus’ death and resurrection? From the perspective of the first writers of the New Testament documents? From the perspective of the New Testament as a whole? From the perspective of later systematizing theologians? On what hermeneutical basis would you prioritize this particular interpretation of Jesus’ death over others?

Recent comments