Actually, I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve attempted to schematize the relationship between history and theology. But I think it is central to the current theological task, so another attempt won’t go amiss. Modern evangelical theology is largely an abstraction. It is a very basic abstraction, very communicable, in many ways very appealing, and it can have a powerful impact on people’s lives. But a price has been paid for this accommodation to the narrow, privatized domain of modern religiosity.

First, it has made it very difficult for us to read scripture well, because the whole chaotic, glorious thing has somehow to be chopped up, pared down, allegorized, and in various ways misinterpreted in order to fit into a very small conceptual box.

Secondly, we have a very weak grasp of what is in fact the central narrative element in the Bible—the concrete historical existence of a people called in Abraham, in reaction against socially constructed blasphemy, to be a corporate, visible and credible witness to the full reality of new creation. In my view, this goes a long way towards explaining why we find it so hard to integrate social and environmental values into our theology and witness.

So what I want to do here is simply to show the difference between a standard evangelical theology of personal salvation (2) and an emerging or new perspective reading of the New Testament (3) as regards their relation to history (1). Whereas modern evangelical theology is largely an escape from history, New Testament theology is very much an engagement with history—that is, with the corporate existence of a people over time.

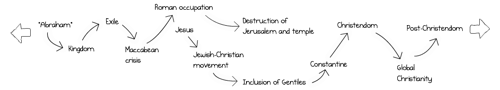

1. As a culture we have reference to a more or less empirical narrative told by journalists, historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, biologists, geologists, and astrophysicists. It starts, in theory, with the big bang, it encompasses what is likely to be the relatively brief span of human history, and it concludes, again in theory, with some sort of unimaginable cosmic curtain call. We are concerned here with a strand in the narrative that begins with the emergence of Israel as a nation, runs through exile and restoration, Roman occupation, the emergence of a breakaway sect that mutates over time into a thoroughly Gentile church, the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, the conversion of the empire to a modified Jewish monotheism, the rise and demise of an expansionist Western Christendom, and the ensuing struggle to redefine Christianity for the post-Christendom era, in which we are all, in our different ways engaged. (Click on the images to enlarge them.)

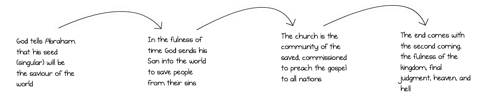

2. Traditional evangelical theology barely makes contact with this historical narrative. Israel exists only as the negative backdrop to the abrupt appearance of grace in Jesus. Acts establishes the paradigm of a church that primarily exists to preach a gospel of personal salvation to the nations. Then nothing much happens of theological significance, with the exception perhaps of the Reformation, until the end of the world, which could happen at any time. At best the corporate narrative of scripture is translated into an allegory of personal salvation: I am a sinner because of Adam (or because of Eve); I cannot save myself by works of religion; Jesus died for my sins; I have new life in him; I must also preach the good news of personal salvation; and I will go to heaven when I die.

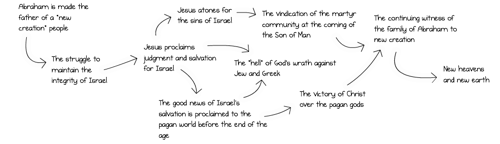

3. The presumption behind an emerging or new perspective account of New Testament theology is that it is at every point an interpretive response to or anticipation of historical events. Genesis 2-3 is as much an account of Israel’s exile as it is of the universal beginnings of sin; Abraham represents the foundational self-understanding of a people chosen to be “new creation”; Israel’s troubled encounter with empire is a key thread in the developing story; Jesus preaches to and dies for Israel; the early prophetic community of his followers interpreted his resurrection as a certain sign of God’s intention to judge both Israel and the nations; the churches share directly in the death and resurrection of Jesus as they face the same hostility for the sake of the future of the people of God; they are vindicated, first by the destruction of Jerusalem, secondly by the eventual conversion of the Greek-Roman empire and the public confession of Jesus as Lord; the family of Abraham in this way inherits the world and embodies new creation on a grander scale.

The corporate narrative is clearly much more complex than the personal narrative. It does not preach well, particularly in a society that has lost all sense of historical existence and is concerned only with the immediate consumption of material and cultural goods. But the corporate narrative has priority biblically, and I think it has to be recovered—not merely by academics but by the church as a whole—if we are to construct a viable long-term future for ourselves following the disintegration of the western Christendom paradigm.

I like your approach Andrew. You have gotten me on board on many places. But I keep wondering how to preach it today? Can we use God's judgment of the Temple and of the Greco-Roman world as similes or metaphors for today? As God judged the Temple or as God judged the Greco-Roman world, so God will judge/can judge the church when she corrupts the Gospel and He will/can judge a nation that resembles the Beast...Does this make sense?

Blessings

@Chris Jones:

Yup, that’s the question. I would resist the temptation simply to use the New Testament narratives as a metaphor for the state of things today. It may be a legitimate argument to make, but we cannot simply assume that there has to be analogy. A narrative theology has to allow for the uniqueness of past events and forces us to reflect anew on our own circumstances. The narrative establishes a trajectory or orientation, but it also places a much greater responsibility on the church now to interpret its situation prophetically.

That said, we can certainly draw conclusions from the New Testament narrative about the seriousness of the church’s vocation. We have to live with the consequences abd implications of Jesus’ death and resurrection even if we have somewhat de-personalized their significance.

There’s also plenty to be preached about the character of the church’s existence as new creation. What is involved in existing effectively as a prophetic embodiment of creation restored? What resources do we have as we work towards that? How do we deal with the tensions and conflicts that happen at the interface between the church and the world? I think that there is considerable scope to develop a new “wisdom” discourse, drawing on Old Testament precedents. How do we disciple not just individuals but communities? There’s more than enough to keep us busy. It just involves a different type of mentality, a different agenda, a different vision for the nature of the church’s existence in the world.

It is awesome to connect with "early adopters" as an intentional change strategy. Those who are not afraid to get on board early on. This way you have more strength/grace to deal with the (inevitable) resistance to creative, theological/hermeneutical change sure to come down the road.

Personally I find much of the emerging church enterprise too close (albeit in a more confusing way) to the traditional understanding of faith, despite its attempt to provide a more appropriate contextualisation of the NT message. There is still a huge gap in the minds of Christians between what faith means "to them" and a more historical-critical approach to the texts from which our understanding of faith should be derived. And the philosophical hermeneutics trends, embraced (implicit or explicitly) by many of the emerging church supporters, are not helping much, in that they are still being used to allegorise the history behind the biblical texts.

This is well articulated, Andrew... though one always needs to judge properly post-Wilkinson-critique, of course.

One of the innate challenges that you don't mention explicitly here, which is true of any 'real' ( rooted in reality and praxis, not only theory) change dynamic (reformation) is that you have keep the existing communities and people going, while the transition takes place. We can glibly dismiss all current praxis, but the status quo never just disappears, no matter how much we might wish it would!

My own somewhat similar missiological understanding has come through a narrative-historical reappraisal that centres on the vitality and significance of the biblical covenants. My personal response has been / is to incorporate this into a discipleship curriculum that I am preparing in dialogue with African leaders and learners. It's about as far from the Western academy as can be, though I've filtered my own perspectives through the discipline of contextual theology, in relationship with Fuller SIS.

@John:

I fully agree with your point about keeping the existing paradigm functioning. I have a couple of thoughts in response, though. The first is that it’s going to keep going whether I want it to or not. The second is that I have had many conversations with people who get the power of the narrative-historical hermeneutic, who find it compelling, even if they don’t agree with me on all the details. They are often struggling with the same questions that I have struggled with. But they are committed at the same time to some form of traditional evangelicalism and the patterns of church life that it sustains. I find that quite encouraging, and it suggests that in a way the church is finding ways to hold in tension the two paradigms as we continue to search for a way forward.

@Andrew Perriman:

Indeed.

I spoke recently with a small group about this reality of holding in tension two realities, philosophies, perspectives. I used two arms stretched wide to demonstrate the bridging role. This places one in a kind of cruciform pose and makes the point that to hold two truths, praxes, theses etc, in tension can demand a form of 'dying' to the easier path of dogmatic, creedal existences.

In ancient settings, such was considered one of the epitomes of wisdom. So I think it may be the right path. And at the same time, it enables people to 'be on board' with exploring fresh perspectives and hermeneutics, without the implicit abandonment that is often the pull associated with cultic developments.

Shalom.

@Andrew Perriman:

One further clarification: I was referring to the need to keep the people and aspects of current operations going through times of transition, so that communities and dependencies don't fall apart.

This is, I think, somewhat different to the 'it's going to keep going one way or another'.

In truth, some things won't continue…at least not for ever. "Change or die." Of course, the Christian way is: die and change!

Recent comments