Robin Parry poses an interesting puzzle about the resurrection of the wicked. I’ve slightly restated it, but it goes roughly as follows:

- At the end of the age there will be a resurrection of both the righteous and the unrighteous for judgment: sheep and goats, wheat and weeds, good-doers and evil-doers, etc. (e.g., Jn. 5:28-29).

- The resurrection of Christians depends on our relationship with Jesus, who is the firstfruits from the dead (1 Cor. 15:20).

- Moreover, our resurrection bodies will be imperishable (1 Cor. 15:42-55).

- So how can the wicked be raised when they are not “in Christ”?

- And will they have the same type of resurrection body as the righteous—as Robin puts it, paraphrasing Augustine: “super-dooper fire-proof, eternal bodies, specially built to endure eternal fire in hell”?

I replied to Robin, but this is an attempt to develop the argument in a bit more detail.

The problem, I think, lies mostly in the assumption that all these passages have the same basic underlying conceptuality, have reference to the same event: the resurrection of all humanity at a final judgment. The shape of the biblical notion of resurrection is more complicated than that. Narrative context and development need to be taken into account.

First, we need to set aside a couple of passages to which Robin alludes but which make no reference to resurrection.

Given the overall apocalyptic frame of Matthew’s Gospel, I think we have to assume that the parable of the weeds (Matt. 13:24-30, 36-43) refers not to a final judgment of all humanity but to an impending historical judgment on Israel. It is a judgment of the living, not of the dead. No resurrection is involved.

In the sheep and goats judgment scene the Son of Man comes to earth to judge the nations (Matt. 25:31-46). Out of the nations some will be judged righteous because they attended to the needs of the disciples as they pursued the mission assigned to them by Jesus, and will have a share in the kingdom. Others will be judged wicked on account of their lack of compassion and will be excluded from the kingdom. No one is raised from the dead.

In other passages, however, an impending judgment is associated with a resurrection of both good people and bad people.

In John 5:28-29 Jesus says that “an hour is coming when all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out, those who have done good to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment”. This looks like an allusion to Daniel 12:1-2, the narrative setting of which is eminently relevant. At a time of great national crisis (“such as never has been since there was a nation till that time”) many dead Jews are raised from the dust of the earth, some to the life of the new age, some to everlasting shame. But they are raised to carry on living on earth. No one is consigned to post mortem eternal fire. The peculiar resurrection of the saints from their tombs at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion appears to be an anticipation of this, whether real or symbolic (Matt. 27:51-53).

Luke has Paul tell Felix that he shares the Jewish belief in “a resurrection of both the just and the unjust” at a “coming judgment” (Acts 23:6; 24:15, 25). This presumably also harks back to Daniel 12:2: it is a resurrection of some Jews, not of all humanity, at a time of national crisis. The Gentile Antiochus will suffer punishment after death, but he is not first resurrected: “But on you he will take vengeance both in this present life and when you are dead” (4 Macc. 12:18). I also suspect that there is a certain ad hominem element to Paul’s apologia here.

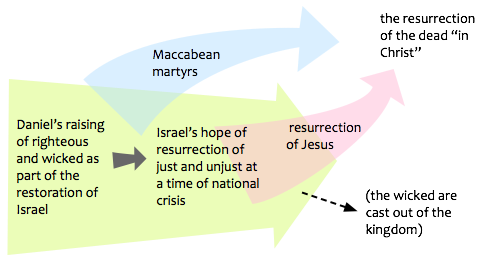

So far, so good…. But it seems to me that the two parts of Daniel’s account of resurrection then follow different trajectories. The Maccabean literature has already introduced the idea of a more personal resurrection of those who are martyred by a Greek tyrant because of their faithfulness to the covenant: “the King of the universe will raise us up to an everlasting renewal of life, because we have died for his laws” (2 Macc. 7:9).

In the New Testament, as we move into engagement with the pagan world, this becomes the prospect that those who suffer on account of Christ—or “with” Christ—will be raised at the parousia, which I argue is the moment when Christ will defeat the pagan oppressor and deliver his followers from their persecutors. So Paul says quite clearly that it is those who suffer with Christ who will be glorified with him (Rom. 8:17; cf. Phil. 3:10-11; Rev. 20:4).

But there is no parallel resurrection of the wicked to accompany this development. Instead, the wicked and faithless—the man without the wedding garment, the foolish virgins, the worthless servant—are shut out of the kingdom.

So for the most part, resurrection is something that happens to God’s people, and there is development in thought through the period, perhaps as the clash with Greek-Roman power becomes more prominent and more ferocious.

We begin with Daniel’s notion of a limited resurrection of Jews, both the just and the unjust, to life on earth following the restoration of Israel, which may be more symbolic than real (equally for Matt. 27:51-53 and John 5:28-29). As we move beyond the ideological framework of judgment against Israel, the resurrection of the wicked drops out of the picture; and we are left only with the resurrection of the Christian martyrs, who will then reign with Christ in heaven.

It is only when we get to the final judgment that all the dead are judged, but even here, in the immediate context, the language of resurrection is missing (Rev. 20:12-13)—though it is implied in 20:5-6. John is unconcerned with the thought that the wicked, whose names are not found in the book of life, have been given imperishable—and therefore indestructible—bodies that will not burn up in the lake of fire. Such a theoretical possibility is outside the conceptual world of this passage. The lake of fire is what it says it is—death, the end.

Recent comments