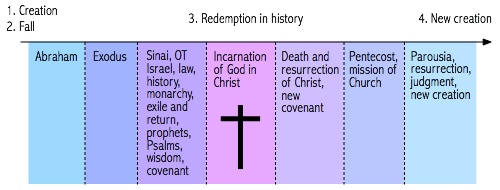

I pointed out last week that in the standard “redemption in history” construal of the biblical narrative—as represented, for example, by Chris Wright’s The Mission of God’s People: A Biblical Theology of the Church’s Mission—all the history is found before Jesus. Nothing of significance happens between Pentecost and new creation. Perhaps this defect is repaired elsewhere in the book, you may wonder. Sadly not. The only chapter that sheds any further light on how Wright understands the narrative after Jesus is chapter 11: “People who proclaim the gospel of Christ”; and what we find here is fully consistent with the diagram.

The background to “gospel” in the New Testament, according to Wright, is the proclamation of good news to Zion that the God of Israel reigns which we find in Isaiah 52:7-10. Three main themes can be drawn from the passage.

1. God reigns (Is. 52:7), which Wright understands to mean that all creation ultimately will be delivered from its bondage to corruption, sin and evil, and that a new order of peace and well-being will be established.

2. God returns (Is. 52:8), which is taken as a polyvalent reference to the rebuilding of the temple after the return from exile, the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, and the final return of Jesus “to claim the whole creation as his temple and to dwell with his redeemed humanity forever” (183).

3. God redeems, which means that he will comfort and liberate first his own people and then the nations.

I think this is broadly correct, but the tendency to reduce the significance of history is already apparent. Basically, as Wright states the matter, the restoration of Jerusalem is treated as the anticipation or foreshadowing of the final renewal of all creation.

This gets Isaiah back-to-front.

The controlling eschatological scenario in the Prophets consists in a restored and glorious city of Jerusalem in the midst of the nations, a beacon of peace and justice, to which the kings of the earth would come to pay tribute, to which the peoples of the earth would come to pay homage to the mighty God of Israel and to learn his ways. The nations are not redeemed: Israel is redeemed, and the nations benefit from this. This is a barely transcendent vision of political-religious transformation.

Isaiah does not make the restoration of Jerusalem a figure for the eventual renewal of heaven and earth. Quite the opposite. The renewal of heaven and earth is a figure for the restoration of Jerusalem.

Notice, too, that the exiles in Babylon hear the gospel only indirectly: they hear from Isaiah that good news is being proclaimed to ruined Jerusalem. It’s the city that matters. It is not the return of the exiles that is good news but the restoration of Jerusalem as the place where YHWH would be king in the midst of the nations. This is not primarily a vision of the redemption of the people, though that is obviously part of the process. It is a vision of the transformation of the political landscape of the ancient near east.

The three themes from Isaiah 52:7-10 then provide the frame for Wright’s discussion of the good news about Jesus as it is presented in the Gospels.

Jesus was and is God reigning

The basic argument here is that Jesus is himself the beginning of God’s reign: “God was reigning in and through Jesus, through his words and his works” (187). So finally, the kingdom of God as the condition of worldwide shalom foreseen by Isaiah has begun in Jesus.

My view is rather that Jesus speaks about the kingdom of God as something that will come or happen or begin in a realistic historical future, within the lifetime of at least some of his followers (cf. Mk. 9:1).

Wright doesn’t provide much support for his argument—to be fair, it’s not that sort of book.

Having read from Isaiah 61:1-2 in the synagogue in Nazareth, Jesus says, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk. 4:21). Wright seems to take this as an announcement of the inauguration of the kingdom of God through Jesus’ presence, there and then. But all Jesus is saying is that he has just been anointed—at his baptism—to proclaim good news to Israel in “fulfilment” of these words in Isaiah. The referent of that good news remains in the future: he announces on that day in Nazareth the future deliverance of the captives and liberation of the oppressed. The blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, and the dead are raised; but the good news that is preached to the poor is that God will transform the political situation of his people in the not too distant future (cf. Matt. 11:4-5).

The other verse that Wright cites is Luke 11:20 (=Matt. 12:28): “But if it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you.” The healings and exorcisms are “evidence that the kingdom of God had indeed come” (187).

The expression “finger of God”, however, looks like an allusion to Exodus 8:16-19. Aaron strikes the ground and “All the dust of the earth became gnats in all the land of Egypt.” The magicians say to Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God.” This is a sign that the Lord is “in the midst of the earth” (cf. Exod. 8:22), but more importantly, it constitutes a warning to Pharaoh that, if he continues to harden his heart, YHWH will intervene dramatically to liberate his people at even greater cost to the Egyptians. In the same way, Jesus’ healings and exorcisms are part of a narrative that will culminate in catastrophic judgment on those who now accuse of him of colluding with Satan and in the elevation of a new covenant people.

Wright imagines the reign of God as an undramatic process of transformation that begins with Jesus and spreads through history, through the lives of those who have entered into it. This is not how Jesus imagined it. Jesus had in mind something far more spectacular. The kingdom that he proclaimed was not a process but the inauguration—on a devastating “day of the Lord”—of a new political-religious arrangement for Israel. Here we have the proper continuation of the Old Testament narrative. Diffusion is not a narrative.

Jesus was and is God returning

According to the Old Testament, Wright says, God would “send a messenger to prepare the way for his return” (Zech. 9:9; Mal. 3:1; 4:5). If John the Baptist was the Elijah-figure who would prepare the way for the coming of the Lord, then surely “the Lord himself was here in the person of Jesus” (188). The entry into Jerusalem on a donkey made it clear that “the king was coming home, bringing God’s righteousness and salvation”. But the New Testament also points to the “further horizon” of the return of Jesus.

The gospel is good news of the God who came, who came back as he first promised, and who will come again, bringing both judgment for those who reject him and salvation for those who heed his call to repent and believe the good news. (189)

Again we see how the standard evangelical narrative model jumps from the last week in Jerusalem to the “further horizon” of Jesus’ second coming. The argument is flawed, I think, at several points.

1. The messenger sent to prepare Israel “before the great and fearful day of the Lord” in Malachi 3-4 is not the same as the messenger who brought good news to Zion in Isaiah 52:7-12. Malachi is a post-exilic prophet. The messenger or “Elijah” is sent to prepare the way of the Lord, who will come to his temple to judge first the priesthood, then the rich and powerful:

But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears? For he is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap. He will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the sons of Levi and refine them like gold and silver, and they will bring offerings in righteousness to the LORD.…

Then I will draw near to you for judgment. I will be a swift witness against the sorcerers, against the adulterers, against those who swear falsely, against those who oppress the hired worker in his wages, the widow and the fatherless, against those who thrust aside the sojourner, and do not fear me, says the LORD of hosts. (Mal. 3:2-3, 5)

2. If Jesus is the one who will enact this judgment against unrighteousness in Israel, it is not because the Gospel narrative equates him with YHWH; it is because the authority to judge and rule over his people will be given to him following his resurrection.

3. The one who returns to Jerusalem riding on a donkey is not YHWH but YHWH’s king, who will be given victory over Israel’s enemies and will reign “from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth” (Zech. 9:10), in quotation of Psalm 72:8. He does not bring God’s righteousness and salvation. He is righteous and has been “saved” (noshaʿ: cf. Ps. 33:16-17; Is. 64:5).

4. There is much that could be said about the “further horizon” of the return of Jesus, but I’ll confine myself here to pointing out that the going and coming that the angels speak of belongs to the continuing apocalyptic narrative of the judgment and restoration of Israel. This is a political narrative, not a cosmic or creational one.

Jesus was and is God redeeming

It’s a huge theological claim, but the biblical evidence presented in support is slight (189-90). The name Jesus means “YHWH is salvation”; he was supposed to have been “the one who was going to redeem Israel” (Lk. 24:21); and Paul says that in Christ “we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins” (Col. 1:24). This falls far short of a demonstration of the assertion that “Jesus was and is God redeeming”. The expectation that Jesus would “redeem” or “liberate” is of the same kind as the disciples’ question in Acts 1:6: “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). The assumption is that he has been chosen or appointed to act on behalf of YHWH in these matters. More to the point here, there is no thought in the Synoptic Gospels that Jesus would redeem the world or creation. He is given the name Jesus because “he will save his people from their sins” (Matt. 1:21).

The gospel according to Paul according to Wright

When we get to Wright’s discussion of Paul’s gospel, overtly political language comes into play:

Through the death and resurrection of Jesus, according to the Scriptures, God has borne our sin and defeated its consequences—enmity and death. And in Christ’s exaltation to God’s right hand (the place of government), the reign of God is now active in the world, so that we now live under the kingship of Christ, not of Caesar. (191)

He also highlights the fact that at the end of Acts Luke has Paul in Rome proclaiming the kingdom of God and arguing, in effect, that “there is another king, Jesus” (Acts 17:7; 28:23, 30-31).

But our hopes are raised only to be swiftly dashed.

Wright concludes that the good news about Jesus was a “universal message for all the nations”, but he develops the point by reference to Ephesians 2:11-18. The universal message is not that God, at some point in the future, will come to rule over the nations but that Gentiles are being included in the “one family” of God, which is “one new humanity”.

So the last historical event of theological significance in the New Testament is in fact the ratification of the baptism of the Roman centurion Cornelius by the Jerusalem council in Acts 15. From that point onwards, we simply have this one new humanity going about the task of inviting others into the experience of reconciliation with God and the somewhat obscure work of redeeming creation. The gospel is “historical” only insofar as it has to do with the “facts of history about Christ and the reality of a new humanity in Christ” (198).

The urgent and obtrusive Jewish apocalyptic vision of the New Testament is entirely disregarded. We misunderstand Paul if we suppose that the inclusion of Gentiles in the covenant people was an end in itself. It was, rather, a concrete sign of the political transformation to come, when Christ would rule over the nations, when the family of Abraham would inherit the world. However we interpret it, the realisation of that political expectation has to be a prominent feature of a credible narrative theology.

Wright argues, finally, that Paul believed that the gospel was the saving power of God “that was transforming history and redeeming creation” (198). But history is not the cumulative effect of individual lives. History is an account of the lives of peoples, nations, cultures and civilisations. It is war and peace, conquest and exile, the rise and fall of empires, oppression and liberation. The transformation of history that Paul had in mind was not the progressive inclusion of people in a new humanity but something much more like the conversion of the Roman empire, the wholesale reform of the dominant pagan culture—an action on the part of the God of history that would surpass the great events of the Old Testament.

And how we are to talk meaningfully about the redemption of creation after two thousand years, as we teeter on the brink of environmental catastrophe, is beyond me. There is no redemption of creation in scripture.

Recent comments