Still going strong here. In chapter three of Gospel Allegiance: What Faith in Jesus Misses for Salvation in Christ Matthew Bates sets out his version of the gospel narrative as a sequence of ten events, somewhat in the manner of the Apostles’ Creed (86-104). (I had a similar go at writing a narrative-historical creed a few years back.) He then addresses some objections to his version from people like John Piper, and rounds it all off with a discussion of the “trinitarian shape” of this gospel of Jesus as saving king. Again, I am enthusiastic about the general tenor of Bates’ ten point creed, but I’m more critical than Scot McKnight appears to be. The devil, as always, is in the details.

1. The king preexisted as God the Son

At best the first line of Bates’ creed is a massive overstatement of the evidence. None of the seemingly creedal statements that we find in the New Testament opens with an explicit and unequivocal assertion that Jesus pre-existed as God the Son. Bates includes it here for theological reasons, not as a point of historical interpretation.

I’ve given my reasons already for doubting the claim that pre-existence is presupposed in Paul’s summary of his gospel in Romans 1:2-4. Bates adds the further argument here that Peter “definitively affirms Jesus’s preexistence as the creator God” when he address the “men of Israel” after the healing of the lame man in Solomon’s portico (88). Peter accuses them of having “killed the Author (archēgon) of life”, whom God raised from the dead” (Acts 3:15).

The word archēgos would normally mean “leader”, “first in a series”, “originator”, “founder”. It is only once applied to God in the LXX and then as part of an odd metaphor in which YHWH is described as the “originator” of Israel’s virginity (Jer. 3:4). Peter later says that God exalted Jesus at his right hand “as Leader (archēgos) and Saviour, to give repentance to Israel and forgiveness of sins” (Acts 5:31). The writer to the Hebrews says that God made Jesus the “founder” (archēgon) of salvation or of faith through suffering in the sense that he pioneered the way of faithful suffering and vindication (Heb. 2:10; 12:2).

In Acts 3:15 Peter means no more than that Jesus was the one by whose suffering God inaugurated the resurrection life which would be the reward for those who would likewise suffer.

The more complex “prosopological” thesis that the New Testament sometimes makes Jesus “the ultimate speaker or addressee of certain psalms” is mentioned and illustrated by reference to Peter’s Pentecost sermon and Paul’s preaching Pisidian Antioch. So it is said that the “Messiah is identified as the true speaker of Old Testament words concerning his incorruptible body and future ascension to the right hand of God” (Acts 2:25-28). Bates makes the case at greater length in his book The Birth of the Trinity (153-54). The lines from Psalm 16 are in the first person; David is writing as a prophet (Acts 2:30-31); therefore, Peter thinks that David has written words that must be spoken by the Christ.

That may be the case, but it hardly requires the presumption of Christ’s pre-existence. Peter says clearly enough that being a prophet David “foresaw (proïdōn) and spoke about the resurrection of the Christ, that he was not abandoned to Hades, nor did his flesh see corruption” (Acts 2:31). David remains the author of the lines, but he wrote them with reference to a future event. He imagines Jesus in the future saying, “you will not abandon my soul to Hades, or let your Holy One see corruption”, etc. (Acts 2:27).

So I don’t see that Bates has provided any evidence for the claim that the gospel about Jesus as the Son of God begins with the claim that Jesus pre-existed as “God the Son”. And just to be clear, my point is not that there is no notion of “incarnation” in the New Testament, just that it serves a quite different purpose; it is not part of this narrative about the good news of the enthronement of God’s Son.

2. The king was sent by the Father

If the fact of pre-existence has not been established, we have to take the sending of the Son in the sense that it is determined by the parable of the tenants: just as God sent his servants the prophets to Israel, so he sent his Son to do the work of a servant and demand the fruit of righteousness. Surprisingly, Bates mentions this parable but does not draw the obvious conclusion. He also notes Peter’s words in Acts 3:26: “God, having raised up his servant, sent him to you first, to bless you by turning every one of you from your wickedness” (Acts 3:26). This is explained by verse 22, where Moses says, “The Lord God will raise up for you a prophet like me from your brothers” (Acts 3:22). The sending of Jesus to Israel does not require a heavenly pre-existence.

3. The king took on human flesh in fulfillment of God’s promises to David

This line is also problematic if there is no presumption of the pre-existence of the Messiah. Incarnation belongs to the Wisdom theme: the Word became flesh, arguably in connection with the baptism of Jesus, and dwelt among Jews. There is really no basis for saying that a Davidic king takes on human flesh. It is a basic category mistake. The most that we can say, if we wish to synthesise, is that the Word or Wisdom of God became (Davidic) flesh, and the Davidic flesh became the exalted Son or King at the right hand of God. I disagree with Bates that the “incarnation is theologically vital” to his reconstruction of the gospel of God’s exalted Son. I think it is quite alien to it.

4. The king died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures

Two issues here. First, Jesus is not a king when he is executed. He is executed perhaps as a royal pretender, a claimant to the throne of Israel, but nothing has happened yet to make him king. He is the anointed Son or servant (Isaiah’s suffering servant is not a king) sent to Israel. The wicked tenants think that they might seize his inheritance for themselves (Matt. 21:38; Mk. 12:7; Lk. 20:14); but it is an inheritance, he hasn’t yet entered into it. People try to make Jesus king by force because he is not yet king (Jn. 6:15). The entry into Jerusalem is a prophetic action. Jesus only becomes king by virtue of his resurrection. Paul uses Psalm 2:7 to make this point: ‘And we bring you the good news that what God promised to the fathers, this he has fulfilled to us their children by raising Jesus, as also it is written in the second Psalm, “‘You are my Son, today I have begotten you’”’ (Acts 13:32–33; cf. Rom. 1:4; Heb. 1:5; 5:5).

Secondly, I agree that the death of Jesus has brought benefits to us, not least forgiveness of sins against the creator and inclusion in his priestly people. I also agree with the emphasis on a corporate salvation. But thinking historically—and indeed corporately—it is better to say that Jesus died for the sins of his people. I would argue that even in 1 Corinthians 15:3 Paul is speaking as a Jew, on behalf of Israel, when he says that “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures”. There is no death for the sins of Gentiles in the Old Testament.

5. The king was buried

Well, no, because he is still not king.

6. The king was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures

Well, no, because he is still not king. The important insight about gospel and kingship is becoming a bully, battering important narrative distinctions into submission.

7. The king appeared to many witnesses

Well, no, because he is still not king. Arguably, he is not even yet Messiah. On the day of Pentecost Peter says that the apostles are witnesses of Jesus’ resurrection, but it is by virtue of his ascension into heaven and exaltation to the right hand of God that he has been made “both Lord and Christ” (Acts 2:32-36).

8. The king is enthroned at the right hand of God as the ruling Christ

Yes, hallelujah! This is the whole point of the New Testament witness. It is “the gospel’s climax and its best summary”, as Bates says, though I think that “Lord” might be more appropriate than “Christ”. Roughly speaking, isn’t it better to say that Jesus became Israel’s “anointed” King, and that Israel’s anointed king then became ruler or Lord of the nations? But I wholeheartedly agree with this: “it is not an overstatement to say that the largest problem within Christianity today is the exclusion of Jesus’s kingship from the gospel” (98).

9. The king has sent the Holy Spirit to his people to effect his rule

Yes, in general terms, but I think it rather misses the point of Jesus’ sending of the Spirit. What the Spirit does is not effect Jesus’ rule so much as empower communities for prophetic witness, particularly in view of the fact that they will face opposition. This is apparent from the passage in Luke which Bates mentions. Jesus tells his disciples not to be anxious about what they should say when they are dragged before synagogues, rulers and authorities, for the “Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say” (Lk. 12:11-12). The Spirit is given at Pentecost not to effect rule but to empower a whole community to prophesy as Jesus had prophesied regarding the coming judgment against and restoration of Israel. Jesus sends the Spirit to equip and empower “those who obey him” (Acts 5:32)—his Jewish followers and the churches that sprang up across the empire—to fulfil their prophetic vocation until the parousia, when Jesus would finally be acclaimed as king by the nations and the suffering of the churches would be brought to an end.

Here’s the crucial point: the Spirit does not make people loyal vassals of king Jesus; the Spirit makes them like Jesus, the Spirit conforms them to the image of the Son who suffered, died and was glorified (cf. Rom. 8:12-30). This is the Spirit of adoption to sonship, to Christlikeness—“provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him” (Rom. 8:17).

Again, I think a weakness in Bates’ account of things is that he gives too little weight to the eschatological dimension of the kingship narrative—the consistent orientation of the New Testament towards future outcomes.

10. The king will come again as final judge to rule

OK, so there’s the eschatological dimension (why do we always have to wait till the end for the eschatology?):

In Jesus’s capacity as king, he will visit his people once again, exercising judgment. Jesus is magnificently described as “King of kings and Lord of lords” in Revelation, as he comes to judge and rule over the nations…. (102)

As the Son of Man who will receive an everlasting kingdom, Jesus will judge the nations, separating people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats (Matt. 25:31-32). Remarkably, in the new world others will sit on thrones as judges with him (Matt. 19:28; Lk. 22:30; 1 Cor. 6:2; Rev. 20:4). So we must insist, Bates rightly says, that the gospel includes “Jesus’s judging function” (104).

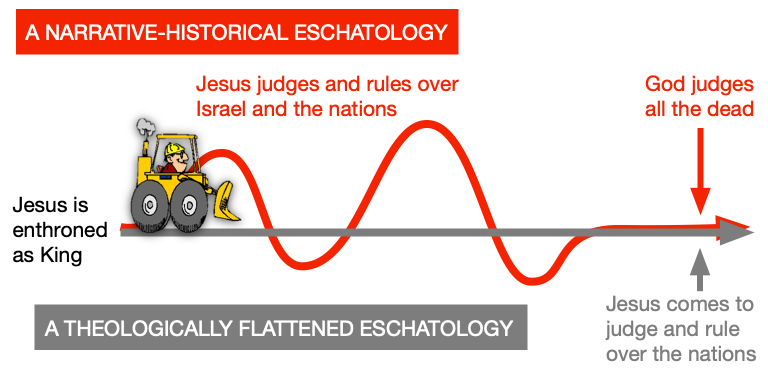

This is all to the good in general terms, but as theologians are won’t to do, Bates has bulldozed the mountains and valleys of New Testament prophecy and has made the rough, uneven ground of history a plain. The method greatly simplifies things, I admit, but it fails to do justice to the contours of New Testament eschatology.

For a start, the coming of Jesus as judge is not a “final” judgment: when the final judgment of all the dead comes, it is God alone who judges, according to what people have done (Rev. 20:11). When Jesus is proclaimed as judge, it is first a judgment of unrighteous Israel that is in view, then a judgment of the nations of the Greek-Roman oikoumenē. These are events—transformations—in a foreseeable future.

First, he will judge and rule over the twelve tribes of Israel as Israel (Matt. 19:28; Lk. 22:30).

Secondly, he will judge the nations on the basis of how they have treated the messengers who were sent out with good news of the coming kingdom of God (Matt. 25:31-46). (Ian Paul has had some good things to say about this recently in a little dispute with the Bishop of Burnley.) Jesus will judge the pagan empires whose idolatry YHWH has for so long overlooked (Acts 17:29-31). The “eternal gospel” is precisely the proclamation that Rome as the supreme enemy of the creator God and his people will be overthrown (Rev. 14:6-11).

It is integral to Paul’s gospel that a day is coming when God will judge the “secrets of men by Christ Jesus” (Rom. 2:16). But this belongs to an argument about the Jew and the Greek—about judgment on the first century Jew who breaks the Law and the Greek who has “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things” (Rom. 1:23; 2:16, 23). Paul does not say that this is a “final” judgment. It is just a day of judgment, when God will act to put things right—and the climactic outcome will be that these nations will abandon their idols and confess Jesus as Lord. That was Paul’s gospel.

Recent comments