What did Christ smell like? Paul says that the apostles—he has in mind at least himself, Timothy, and Titus—are the “fragrant aroma of Christ to God among those being saved and among those perishing” (2 Cor. 2:15). Careless readers of scripture that we are, we happily assume that the goal of Christian spiritual growth or discipleship is to become more Christ-like, to be conformed to his image, to give off the sweet smell of Jesus in the world. But when we look closely at how Paul develops these themes, a rather disconcerting picture emerges.

This is a painful letter to read. Paul does not go into details, but it is clear that the apostles have recently endured intense hardship in Asia, perhaps in Ephesus, to the point that they despaired of life itself (2 Cor. 1:8). In this regard, they have experienced in abundance both the sufferings of Christ and the encouragement that comes from knowing that God will raise from the dead those who suffer and die for the sake of Christ (2 Cor. 1:9; cf. Phil. 3:10-11).

Two further setbacks are narrated before we get to the “aroma of Christ” passage. First, there has been a breakdown in their relationship with the church in Corinth, and Paul has to work hard to defend their actions and convince them of the integrity and authenticity of their apostleship (2 Cor. 1:12-2:11). Secondly, he had to turn down an opportunity to proclaim the gospel of Christ in Troas because he did not find Titus there. In frustration he has crossed over into Macedonia, from where, presumably, he writes this letter (2 Cor. 2:12-13).

So things are going rather badly, and he fears that the Corinthians will take it as evidence that he and his colleagues are no better than so many other unprincipled purveyors of a debased word of God. His answer to this is to insist that even under—or perhaps precisely under—these unfavourable conditions the knowledge of Christ is made known to people (2 Cor. 2:14-16).

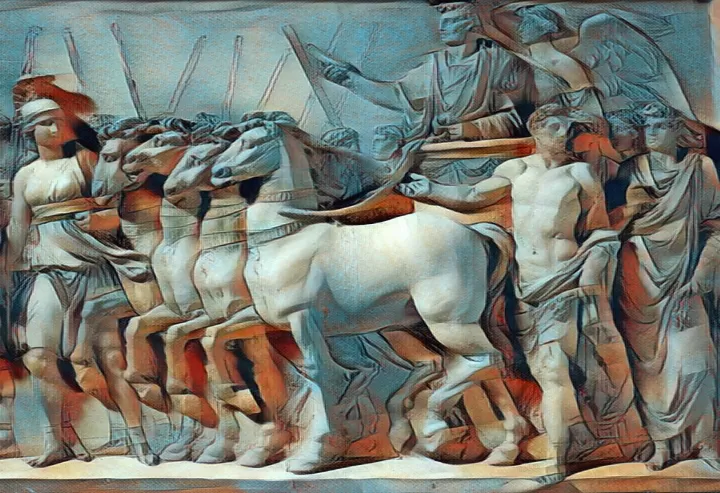

The meaning of the “triumph” figure in verse 14 is not certain. It could mean that the apostles are presented nevertheless as triumphant—either they are “caused to triumph” or they are likened to successful Roman generals in a triumphal procession. But it seems more in keeping with the tenor of Paul’s argument to think that the metaphor evokes the humiliation and disgrace of a conquered people, which is how the apostles have appeared to both Jews and Greeks. The point would be much the same as 1 Corinthians 4:9, 13:

For I think that God has exhibited us apostles as last of all, like men sentenced to death, because we have become a spectacle (theatron) to the world, to angels, and to men. … We have become, and are still, like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things.

But then it is on this basis that they become the means by which the fragrance of the knowledge of Christ is made known in every place (2 Cor. 2:14). Paul is not talking about proclamation of the gospel here, which would shift the emphasis to the rule of the risen Christ as Son of God (cf. Rom. 1:1-4; 2 Cor. 2:12). What he means, I think, is that the apostles are publicly and realistically embodying or re-enacting the humiliation and disgrace of Christ.

People will know something of the paradoxical, counter-intuitive wisdom of God expressed in the suffering of Jesus through the suffering of his apostles. They leave the ambiguous acrid smell of the crucified Jesus in the air as they pass through. To some it is a smell from life to life; to those perishing it is a stench from death to death. Even in the earlier letter we learn that the preaching of the word of the cross—folly to those perishing, the power of God for those being saved—was undertaken in a state of wretchedness that perhaps foreshadowed the recent humiliation of the apostles: “I was with you in weakness and in fear and much trembling, and my speech and my message were not in plausible words of wisdom” (1 Cor. 2:3–4).

The theme of the close, specific, and self-conscious identification of the apostles with Christ in his suffering runs through the next three chapters. Paul continues to speak on behalf of the Jewish apostles “Are we beginning to commend ourselves again? …our sufficiency is from God, who has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant” (2 Cor. 3:1, 5-6). The Jew who turns from Moses to the Lord sees the glory of the crucified Christ and is transformed into that image. He exchanges the glory of the moribund covenant of Moses for a life-giving new covenant in the Spirit, but the transformation comes through weakness and suffering—a most peculiar competence.

We have the same argument in Romans 8. All who have the Spirit are “children of God,” but it is only those who suffer with Christ who are “fellow heirs with Christ” and can expect to be glorified with him (Rom. 8:16-17). It is those who cry, “Abba! Father!” in their own Gethsemane moment, faced with death, for whom the Spirit intercedes “with groanings too deep for words” (Rom. 8:15, 26-27). It is under such extreme circumstances—perhaps only under such extreme circumstances—that “all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” The point is that some of the believers in Rome have been chosen and predestined “to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers.” These will be glorified with Christ (Rom. 8:30). The family of the firstborn from the dead is a rather exclusive fellowship, consisting only of those who suffered as Jesus suffered and were raised as Jesus was raised.

What this meant for the apostles is set out in the continuation of the argument in 2 Corinthians 4-5. When Paul says that “we have this treasure in jars of clay,” he is not speaking of believers in general, he is speaking of the apostles. Earthenware vessels make good repositories for valuable documents (cf. Jer. 39:14 LXX), but they are also easily smashed (cf. Jer. 19:11 LXX). The apostles are afflicted, perplexed, persecuted, struck down, “always carrying in the body the dying (nekrōsin) of Jesus”—probably not here the past death of Jesus but the relentless, present experience of dying for his sake. “For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake…” (2 Cor. 4:11).

By the same token, of course, they are confident that God will raise them from the dead as he raised Jesus from the dead (2 Cor. 4:14). At the parousia, when Christ at last is confessed as Lord by the nations, the resurrected martyrs will be rewarded and glorified on account of the communities of eschatological faith which they founded (cf. 1 Cor. 3:8, 14; 1 Thess. 2:19). Whether they are alive or dead at that moment, the apostles—not believers in general—“must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in the body, whether good or evil” (2 Cor. 5:10).

So before we glibly appropriate these powerful metaphors and the associated theology for ourselves, we need to get to grips with the sharply focused apostolic experience to which they are applied. We should hesitate to build ourselves up at the expense of the biblical narrative. We are not, mostly, the aroma of Christ—certainly not in the sense that Paul intended it. We are not being conformed to the image of Christ.

Recent comments