Following up on The battle between theology and history for the soul of the church: 24 antitheses, I want to clear up what looks to me like an area of confusion regarding the relationship between theology, narrative and history. In a couple of helpful comments Ted Grimsrud argues for what he calls a "practice-oriented theology", which in his view occupies more or less the same space on the chart as the narrative-historical approach. He contrasts a theology that is mainly about doctrine and abstract ideas with a theology that is "part of the story of bringing healing into a broken world". Such a theology is historical in the sense that "it happens in our historical existence, our lives in this world".

So another contrast would be between theology that focuses on life after death (and is "ahistorical") and theology that focuses on life before death (and is "historical").

I would certainly agree that theology should be practice-oriented, though I am not convinced that the story that begins with Abraham is primarily one of "bringing healing into a broken world". But I also want to point out that if we begin with the practice of theology, we are likely to think of it as "historical" only in a synchronic or existential sense, in contrast to what is transcendent or "ahistorical". The narrative-historical approach is interested in history as a diachronic phenomenon. I suggest to Ted that his practice-oriented theology is (in practice) narrative but not narrative-historical. This is not particularly a criticism. It is a way of pointing out that we need our "theology" to do different things. Ted is more interested in application than in biblical interpretation. I am more interested in biblical interpretation than application. Both are important. The challenge is to connect the two without sacrificing the integrity of one or the other.

How theology, narrative and history differ

Theology largely abandons both the narrative and the historical dimensions of scripture. There is a rudimentary overarching story—basically a mythology—which goes from 1) creation and fall to 2) Jesus and the foundation of the church at Pentecost to 3) the second coming and final judgment. But what happens between the beginning and the middle is of theological interest mostly only insofar as it prefigures Christ; and what happens between the middle and the end is of interest only insofar as it is an outworking of the paradigm of the New Testament church. Theology, in other words, aims to transcend history by dealing in either rational or mythological abstractions. But although theologians tend to think that their systems are timeless, theology has never managed to drag itself out of the churning seas of historical change on to some unshakeable foundationalist piece of land.

A narrative hermeneutic approaches the scriptures rather differently. In [amazon:978-0801027468:inline] Craig Bartholomew and Michael Goheen argue that the "Bible provides us with the basic story that we need in order to understand our world and to live in it as God’s people". The Bible was not written as a "series of propositional truths" or as the basis for systematic "confessions". It is only as we learn to read it as a story that we will “feel the full impact of its authority and illumination in our lives”. The problem with a narrative theology is that it tends not to be especially interested in the frame of reference. Narrative theology respects the form of the biblical material. But in practice it can be just as much an escape from history as the rational-mythological theologies. Bartholomew and Goheen implicitly think of scripture as providing a story that embraces or frames our world rather than as a story that precedes our world, which is what history is. The point can perhaps be made paradoxically: narrative theology reduces the past to narrative-without-history and the present to history-without-narrative.

A strictly historical hermeneutic will deal with the texts according to prevailing historiographical criteria. A modern historical approach will want to know whether the texts can be trusted with regard to their statements of fact. Are the texts really what they purport to be? Was reality really as they describe it? A postmodern historical approach, if that is not too much of an oxymoron, will be more of an enquiry into the constructed nature of what we call "history". It is more interested in the relation between the text and the author or community that produced the text than in the relation between the text and the events narrated.

This brings us nicely to the narrative-historical approach, which regards scripture as the story told by a historical community to make sense of its historical existence in relation to the living God. The fact that this is at every point the story of the community's relationship with the living God means that it is an intrinsically theological story, but such theological reflection remains bound up with the concerns and constraints of the historical context. This clearly raises the problem of how such a reading of scripture is to be applied today.

How these readings are applied today

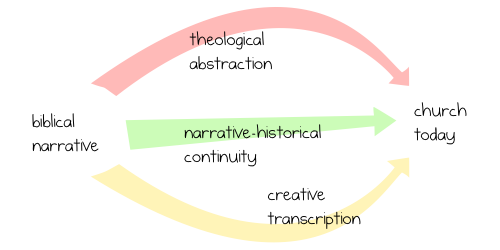

Theology applies biblical "truth" by way of the abstractions that it has created, which is why it tends to be regarded as highly cognitive or propositional or dogmatic. Abstractions don't lend themselves to practical application. It is, of course, true that a rational-mythological theology can drive personal conversion and life-transformation, because that is basically what it has abstracted from the texts. The problem is that a great deal has been left behind in the process, including the fundamental narrative shape of the texts and their relation to history. Theology, therefore, both misinterprets scripture and radically reduces or distorts its applicability.

Narrative gets applied essentially by way of what John Barton calls "creative transcription", which in most cases probably comes down to analogy.

A strictly historical approach to the biblical texts is necessarily disinterested in contemporary application, though many would regard this disinterest as a stumbling block to contemporary application.

The narrative-historical approach, finally, locates scripture firmly in the past but highlights the narrative-historical continuity between then and now. This is how Wright's well known five act play model works: we are a group of actors given the task of developing the story that has emerged from the first four and a bit acts of the play. What connects past and present, what safeguards the continuing practical relevance of scripture, is the concrete historical existence of the community that was formed, or re-formed, by the events narrated in the New Testament. Most importantly, this is a trinitarian existence: the church is in covenant relation with the same God, acknowledges the risen Jesus as its Lord, and lives practically by the power of the Holy Spirit. Neither theological abstraction nor creative transcription are ruled out, since they can be found in scripture itself; but as in scripture they work in principle within the narrative-historical framework. My argument is that this is a very robust and powerful way to read the biblical texts.

what happens between the beginning and the middle is of theological interest mostly only insofar as it prefigures Christ; and what happens between the middle and the end is of interest only insofar as it is an outworking of the paradigm of the New Testament church

Yes — I think this broadly reflects how I see scripture, but I don’t see why it is described by you as ‘mythology’, in contrast with a narrative history, or why theology as it has largely been practised should be described as dealing with ‘abstractions’, in contrast with the supposed concern of the OT community only with a theology as it interpreted their narrower history.

I’d have thought the selective basis of history as presented in the OT shows a great deal of interest in the supposed ‘mythology’ of a ‘rudimentary and overarching story’. The echoes of Eden and the ‘recovery’ programmes are an important part of the early chapters of Genesis, leading up to Abraham, the most important agent of restoraton of them all, part of which was the sojourn and Exodus from Egypt, also predicted to him. The ‘echoes’ continue in the Writings and the Prophets, in Isaiah perhaps most of all, where they appear as a ‘second Exodus’, a fulfilment of Israel’s history with universal implications. It is significant that the climax of Jesus’s story, his death and resurrection, was interpreted by him through an Exodus Passover meal.

The major part of Abraham’s significance was worldwide, and not limited to a geographically local people. Israel’s problem was a constant inability see, and a rejection of, that larger picture, though there are frequent reminders of it in the OT, in psalms and prophets as well as in books like Ruth and Jonah.

When the history of Israel is traced through the five major covenants, underlying them all is one main covenant purpose, which was to restore creation. Even the temple, that apogee of Jewish self-identity, was itself a microcosm of creation. The six-day creation of Genesis was the archetype of temple dedication, and the agency of king and priest had central participatory roles.

Paul’s grasp of this universal story and purpose was so comprehensive that he effortlessly moved from Jew to Gentile with his gospel of the Kingship of Jesus, using Isaiah in particular as a commission (49:6b being the part which refers to the whole). His understanding and practice validly frame our interpretation of the story.

I don’t see the antithesis between a ‘mythological’ overarching story, and a theological interpretation by the historic community of Israel of their history. To me, they are one and the same thing — with the qualification that Israel’s main issue with YHWH became one of wishing to interpret and restrict His blessings and significance to themselves ethnocentrically. This is Paul’s criticism of Israel in Romans 9-11, and his argument in Romans as a whole that the worldwide covenant purpose of YHWH through Israel had nevertheless been fulfilled.

@peter wilkinson:

Peter, I think you’ve misunderstood my point, which was that modern evangelical / Reformed type theologies tend to work either with theological abstractions or with narrative abstractions which are essentially mythological rather than historical. By “mythological” I do not mean that creation, fall, redemption, final judgment are not real, only that they are not really history. My argument was that history, whether Old Testament history, New Testament history or the history of the church gets excluded from the mythology of beginning, middle and end. This is very different to saying that the Old Testament and New Testament do not engage with an overarching narrative.

Recent comments