I’m about a third of the way through Dale Allison’s book The Historical Christ and the Theological Jesus. So far, it’s been an introspective, ambivalent—if not vacillating—but engaging reflection on the difficulty of doing historical Jesus research in a way that is theologically or religiously useful. Here’s one way of pointing out the challenge:

Remarkably, many pew-sitters are happily oblivious of what has been going on in the thinking world for two and half centuries. They have somehow avoided most or even all of the serious intellectual commentary on the Gospels since the Enlightenment. (3)

I think that we need to be doing a lot more to bring the two sides together in a constructive dialogue—the critical scholars, on the one hand, and the practitioners and pew-sitters, on the other. But that’s not the issue I want to pursue here.

In chapter 2 Allison addresses the question: “How much history does theology require?” Can historical-critical exegesis provide a useful starting point for theology? One major difficulty, he suggests, is that “presuppositions extrinsic to the texts govern how we interpret them” (8). To illustrate, he takes Jesus’ saying in Mark 13:26 about the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven, and outlines four modern readings of the verse from different theological-religious perspectives.

It’s assumed that all four positions agree on a historical meaning, what the verse meant: that Mark “expected someday to look up into the sky and to see Jesus riding the clouds”. But then the interpreters scurry off in very different directions.

1. Well, actually, a fundamentalist won’t go anywhere. She will insist on reading the text literally, according to the supposed historical meaning. She will agree with Mark that Jesus will one day descend bodily from heaven.

2. A liberal Protestant will argue that the modern worldview doesn’t allow us to believe that a person will descend from the skies on a cloud, so we must read the verse as a mythological statement: it is a “way of affirming that the God of Jesus Christ will set things right in the end”.

3. A sympathetic non-Christian naturally discounts the theological content of the passage and will find the “real meaning” of the verse in its expression of a universal human need for hope.

4. An unsympathetic non-Christian will say that Mark was simply wrong and that “Christians are deluded, their faith vain”.

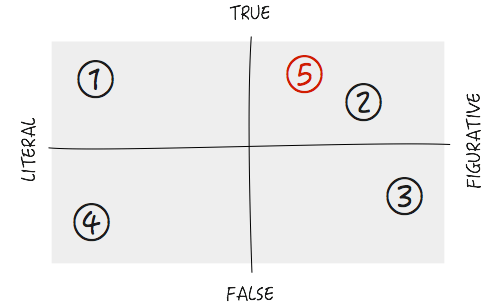

We can chart the options roughly as follows. Option #3 is a little difficult to place, but “people always need hope” can hardly be construed as an affirmation of the truth of the story. I will propose a fifth option at the end.

The lesson that Allison draws from this is the hermeneutical commonplace that “a text is never the sole determinant of its interpretation or application” (39). I wouldn’t argue with that. But I do want to question the historical-critical premise of his illustration, recognising that it may only have been hypothetical.

There are some general points to be made first about the interpretation of the saying. At least, these seem to me to be the main contextual factors that determine its meaning.

- “But in those days, after that tribulation” directly links the coming of the Son of Man to the events surrounding the desolation of the temple and the flight of Jesus’ followers in Judea to the mountains (Mk. 13:14).

- The description of disorder in the heavens (sun and moon darkened, stars falling, powers shaken) presumably serves the same purpose as it does in the Old Testament. The language brings out the theological import of catastrophic earthly events as decisive acts of divine judgment (cf. Is. 13:10; 24:23; Ezek. 32:7; Joel 2:10, 31; 3:15). It does not signify the end-of-the-world; it signifies the end of Babylon’s world or of Israel’s world.

- Jesus expected these things—including the coming of the Son of Man and the sending out of the angels—to happen before “this generation” passed away (Mk. 13:30). The point is reinforced by the earlier saying about the Son of Man, at his coming, being ashamed of those who were ashamed of him “in this adulterous and sinful generation” (Mk. 8:38). However we interpret the coming of the Son of Man, it must have something to do with the fate of the current generation of Jews, exemplified earlier by the Pharisees who demanded from Jesus a sign from heaven (Mk. 8:11-12). The coming of the Son of Man to condemn “this adulterous and sinful generation” of Jews coincides with the coming of the kingdom of God “with power” before the death of “some standing here” (Mk. 9:1).

- The coming of the Son of Man with the clouds of heaven in Daniel 7:13 also has nothing to do with the end-of-the-world. If Jesus is reworking Daniel’s vision for his own purposes, we should start from the assumption that a similar historical framework is in place. It is a vision of the eventual vindication of the suffering righteous in Israel, who are given the dominion which was formerly exercised by the inhuman beastly kingdoms.

So the saying about the coming of the Son of Man in Mark 13:26 belongs to a coherent story about impending judgment on Jerusalem and the implications of that event for the disciples, for which the vision of Daniel 7:13-27 constitutes a crucial interpretive background.

Now here’s a question I think we might ask. Why would Jesus—that is, the Jesus who is a protagonist in Mark’s telling of the story—think of the coming of the Son of Man as a literal descent on the clouds from heaven to earth when Daniel clearly meant his language to be understood symbolically?

Daniel’s vision of “one like a son of man” approaching the Ancient of Days is no more to be taken literally than the vision of the beasts coming from the sea or of the battling ram and goat in chapter 8. Are we to suppose that Jesus did not grasp this, that he lacked the literary sensibility to realise that Daniel was not attempting to depict an event visible to people on earth? Even if we take the figure in human form to be an angel, as some scholars would argue, we must still allow that what is seen in the vision is played out in quite different terms on earth.

There is more directly relevant evidence that Jesus would not have expected the statement to be taken literally.

- When he says to Caiaphas that the priests and elders of the people “will see (opsesthe) the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven” (Mk. 14:62), he is not speaking of a literal sighting. Jesus means, roughly, that the current leadership of Israel will be confronted with the fact of his vindication and enthronement, expressed in the symbolic language of Psalm 110:1 and Daniel 7:13.

- Stephen has a vision (“Behold, I see…”) of the heavens opened and “the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God” (Acts 7:56). We do not suppose that he literally saw the sky torn apart to reveal Jesus in heaven. The language of heaven being opened is, of course, familiar from Revelation: “Then I saw heaven opened, and behold…” (Rev. 19:11).

- Finally, Jesus says to Nathanael, “Truly, truly, I say to you, you will see (opsesthe) heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man” (Jn. 1:51). As with the words to Caiaphas, Jesus has constructed a new vision concerning himself out of two Old Testament texts. When he says to the disciples “you will see”, he means only that they will come to understand the significance of what is being stated in figurative language.

There appears to be no good exegetical reason, therefore, to retain the premise that Mark expected Jesus to return physically to earth someday on the clouds of heaven. Rather, his Jesus uses visionary and symbolic language to speak about the significance of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple for the mission of his disciples. Essentially, it would mark the end of their suffering, their public vindication, and their participation in the reign of Christ throughout the coming ages. All this would become apparent, first to Israel, then to the nations.

So I suggest that we have a fifth interpretive option, which allows us to affirm the theologically important truth of the saying without creating a disjunction between what-it-meant and what-it-means. What it means for the church now is what it meant for the disciples then.

5. The narrative-historical interpreter would reject the premise that the historical meaning is the literal one—that Mark expected to see Jesus bodily descend on a cloud from heaven. When Jesus speaks of seeing the fulfilment of some Old Testament vision or other, the language is not to be taken literally as referring to angels ascending and descending from heaven or a human figure travelling on a cloud. In that respect, the fundamentalist is wrong and the liberal Protestant is right. But the liberal Protestant has gone too far in removing the saying from its historical setting. The coming of the Son of Man has to do with God putting things right, yes, but in the particular narrative-historical context of the mission of the disciples with regard to the fate of Jerusalem in the first century.

Great article, Andrew. Thanks for writing it.

BTW, I appreciated the long dialogue with Don Preston over the identity of Babylon in Revelation. I came away greatly challenged and edified by the respectful discourse. In the end, I still believe the evidence lies more strongly with Jerusalem as the identity of Babylon, but I still think we on both sides have much more in common than uncommon.

“What it means for the church now is what it meant for the disciples then.” But this wasn’t the case for the Jesus and the apostles, right? “Then Jesus took them through the writings of Moses and all the prophets, explaining from all the Scriptures the things concerning himself.” Luke 24:27

When they looked back, they took material, images, events and applied it to their present. Futurists do the same with NT double meaning argument. It’s a view One I find hard to wrestle out of when it seems that approach is used by the NT writers.

You may be right, Eric, but the point can be overstated.

We don’t know how Jesus interpreted the scriptures for the disciples on the way to Emmaus.

The issue in the present case is not whether Jesus reapplied the Son of Man narrative but what he has reapplied it to. Clearly he has taken it out of its original context, but the question is whether he has borrowed it to redescribed a historical crisis similar to that envisaged in Daniel 7-12 or to speak of a final cosmic event. So we still have to ask whether the borrowing and reinterpretation is appropriate—does it maintain narrative coherence.

Too often, I think, we make this problem worse for ourselves by reading later theological conclusions back into the New Testament and then finding that we can’t get the text to fit the Old Testament prophecy. I would give the Immanuel “prophecy” as a good example.

Recent comments