The narrative-historical method reduces the significance of Jesus, which creates an obvious problem for traditionalists. Perhaps “reduces” is asking for trouble. Let’s say that it refocuses our understanding of the biblical figure of Jesus, though the sharper perception comes at the cost—or benefit, depending on how you look at it—of a restricted depth of field. Here’s what I mean, roughly….

The birth of Jesus

Theological tradition says that God became flesh in the birth of Jesus for the sake of all humanity, if not the whole cosmos. From a historical point of view that is a later theological reading—or misreading—of the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke, and probably also of the Prologue to John’s Gospel.

Matthew and Luke make it clear that the conception of Jesus was miraculous. But the meaning of the miracle is not that God and man are conjoined in the person of Jesus. It is that the extraordinary circumstances of his birth mark it out as a prophetic sign.

Just as the birth of a boy named Immanuel was a sign to Israel that God was with his people at a time of crisis, both to judge and to save, so the birth of a boy named Jesus is a sign to Israel at a time of great crisis that God is again present with his people, both to judge and to save (Matt. 1:21-23). Luke perhaps has superimposed on this the later Isaianic theme of the birth of a Davidic ruler (Is. 9:6-7; Lk. 1:31-35).

But doesn’t John say that Jesus is the Word become flesh?

Yes, he does, but he does not say that this happened at Jesus’ birth. The Word is more closely identified with God in John’s Prologue than is Wisdom in Jewish tradition—the Word was not only with God but was God or was divine. But the thought is much the same: the creative power of God has entered into the world to bring about something new. Since this entrance into the world is framed by the account of John’s testimony, it seems to me that the Word becomes flesh and dwells among us at the baptism of Jesus, when the re-creative ministry of Jesus is inaugurated.

The birth of Jesus, therefore, in the New Testament is not the supra-historical coming of God—or of the eternal Son—into the world but the beginning of a God-driven undertaking to deliver his people from their enemies and establish a new Davidic king. The “world” is little more than an astonished spectator at this great act of salvation.

The humanity of Jesus

Orthodoxy rightly asserts that Jesus was fully human, but this is usually taken to mean that he was the ideal human being or Everyman. The Jesus we encounter in the New Testament, however, is a first-century Jewish, presumably heterosexual, male. He was not a woman, he was not black, he was not old, he was not gay, he was not married, he was not a father, he was not disabled, he was not a lot of things. He is a second or last Adam only in the sense that he was the first of many to experience resurrection and acquire a “spiritual body” (1 Cor. 15:45-49).

We also hear it said that he knows our every weakness, has been tempted in all ways as we are, has experienced our afflictions. He knows what you are going through because he’s been through it himself.

To be sure, we read something along these lines in the letter to the Hebrews, but the point is really quite narrowly made. We have a great high priest who “has passed through the heavens.” That is, Jesus was opposed, arrested, tortured, executed, raised from the dead, and exalted to the right hand of God as a priest-king after the order of Melchizedek (Heb. 4:14). Therefore the writer exhorts his readers to hold fast to their confession—to stay true to their vocation through to the end, no matter how long it takes, no matter how much they must suffer.

It is specifically in this regard that Jesus is able to sympathise with their weaknesses, for he “has been tempted as we are, yet without sin”—he “endured from sinners such hostility against himself” (Heb. 4:15; 12:3). The weaknesses that the risen Jesus understands are those which are exposed by opposition, rejection, and the threat of death. For the writer of the letter this Jesus is not the ideal man who has known the totality of human frailty; he is the ideal Jewish martyr, the pioneer of their faith in the world that was coming (Heb. 12:2).

The ministry of Jesus

The life and ministry of Jesus has generally been of little interest to orthodoxy, which requires only that he was incarnated somewhere in the middle of history, that he died for the sins of the world, that he was raised from the dead, and that he will come again in person right at the end to wrap things up.

More recently Jesus has been co-opted as the paradigm for progressive Christian action on account of his antagonism towards the self-righteous and complacent religious leadership of Israel and his clear bias toward the poor and marginalised.

With more justification he has been adopted as the standard for incarnation-missional leadership, but again the historical context drops from sight. Jesus does not establish a general pattern of missional practice for his church throughout history. The most we can say is that he established a pattern of missional practice for his immediate Jewish disciples for the period leading up to the war against Rome.

The mission to the Gentiles, which gives rise eventually to the church as we know it, is conducted on quite different terms. Paul shows no interest in, and little knowledge of, the pattern of Jesus’ earthly ministry. If anything, he expects people to be disciples of himself and the apostles. The post-resurrection dynamic is directed not towards the earthly Jesus in Galilee and Judea but towards the exalted Lord at the right hand of God in heaven.

The death of Jesus

Jesus’ death in the New Testament is not a great meteorite that falls from heaven into the boundless ocean of human history, sending waves of redemptive energy travelling forwards, and perhaps backwards, through time. It is a rockfall, caused by a localised storm and flood, into the river of Israel’s history, dramatically changing its course in the first century.

According to the majority New Testament witness Jesus died for the sins of Israel. This is the scope of the saying about the Son of Man coming “not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mk. 10:45). I think it highly likely that Jesus had in mind the words of Isaiah 53:11-12: the righteous servant will make many to be accounted righteous, he will bear their iniquities, he bore the sin of many. But it is Israel alone which benefits from the redemptive suffering of the servant. He was wounded for the transgressions of Israel, he was crushed for the iniquities of Israel (Is. 53:5).

An unexpected consequence of his death for Israel, however, was that Gentiles were caught up in the flow of that river, and in this narrative-historical sense I can say today that Jesus’ death made it possible for me to be part of God’s story despite my sins. But this is still a far cry from the rationalising theological paradigm, which makes no reference to the existential crisis faced by first-century Israel.

The exaltation of Jesus

The Apostles’ Creed says that Jesus ascended into heaven, sits at the right hand of God, the Father Almighty, and will come again to judge the living and the dead. It is good that the apocalyptic language has been retained, but it is again the case that the historical reference of that language has been allowed to fade from sight.

The central conviction of the early church was that a disgraced and executed demagogue from Nazareth had been given the authority to determine the real future of Israel and his followers. The heavenly status of Jesus was a matter of pressing historical significance. Whereas in the past it was God who came to judge his people and the enemies of his people, the belief of those who had come to know the living Lord was that Jesus would “come” on YHWH’s behalf to execute judgment—first against Israel, then against the hostile pagan nations of the Greek-Roman world. The eschatological outlook of the New Testament was much more limited than our own.

It’s not all bad

The effect of this refocusing has been to reconfine Jesus to a particular historical setting and outlook after centuries of theological liberation. People will complain, but my defence would be two-fold. First, the “historical” Jesus still impacts the life of the church today—on the one hand, he changed history and we gain from that; on the other, he remains our living Lord, seated at the right hand of God for our sakes, until the last enemy, death, has been destroyed. Secondly, we make room for the God of history to take centre-stage again at a time when we are facing, as his servant people, a historical crisis of biblical proportions.

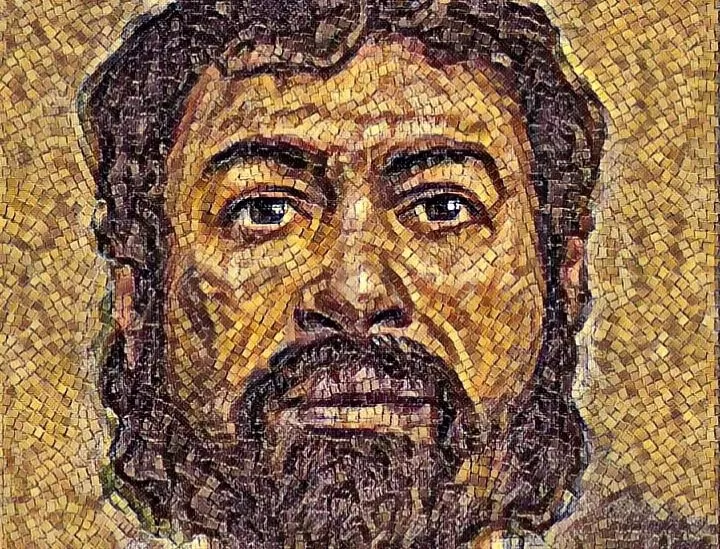

Thanks for this. I think American evangelicals need a reminder of this, particularly since it seems to follow from the implications of historical Jesus studies as well as a historical-narrative approach to the Bible. But, of course, you run the risk of fueling fears and charges of heresy, even with a title like this! On another note, what is the image source on this post? It reminds me of the forensic reconstruction of what Jesus may have looked like from a documentary a few years ago.

The narrative-historical approach certainly embraces historical Jesus studies. I’m just trying to make the historical Jesus part of the bigger story and someone worth believing—a worthy object of “evangelical” interest. Of course, the shift from theological orthodoxy to historical “orthodoxy” will be difficult, but at least the biblical texts are on my side, more or less.

As for the image, it’s available on the web, but I couldn’t find a source. In any case, it’s not this one.

Just today, before reading this post, while (literally) tending the bit of garden under my stewardship, I was thinking about the question of “limits” in Mt 28 “Great Commission”, that is so beloved of US Evangelicals.

Does Jesus’ promise to be “with” the apostles unto the fulfillment of the age suggest the possibility that Jesus is no longer “with” the churches in the way he was prior to the crossing of the 1st and 2nd eschatological horizons?

–—

Would it be fair to say that there is a connection between the suppression of the prophets as spokespersons for the Deity in the early churches and the loss of a self-narrative-within-history in favor of abstract timeless theology?

While I’m not enthusiastic about what I am seeing on this side of the pond, perhaps there’s an upside to the interest in “relevant to the present time” prophecy.

Since ancients believed new life was created by the male’s seed, couldn’t Matthew and Luke’s accounts be establishing a uniqueness and superiority of Jesus over normal humans? Couldn’t the fact that God caused Mary to become pregnant set Jesus apart in these accounts as more than human (a Jewish Hercules)?

@Peter:

I think it’s possible that myths of divine conception are somewhere in the background, but Matthew and Luke do not show any obvious interest in the idea.

Matthew’s appeal to Isaiah 7:14 brings a very different narrative into play: the boy Immanuel is a prophetic sign, not a god-man.

The connection is attributed to the Holy Spirit rather than to any more concrete expression of divine presence such as the angel of the Lord. Is it likely that the Spirit would have been thought of as “physically” impregnating Mary?

According to Luke, it is at Jesus’ baptism that the Holy Spirit descends upon him “in bodily (sōmatikōi) appearance as a dove” (Lk. 3:22). Perhaps the conception anticipates this.

You would think that Matthew in particular would be careful not to confuse Jesus with the pagan analogies.

Luke makes no reference to Isaiah 7:14, but he preserves the detail that Mary was a virgin. This is not necessary if the point is that she has been impregnated by a god and that her child is therefore super-human.

I could imagine that non-Jews in the Greek-Roman world joined the dots differently, but for Luke “Son of the Most High” and “Son of God” are human descriptors—this is the one who will be given “the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end” (Lk. 1:32-33). To be a son of the Most High you only needed to love your enemies, do good, and lend without expecting anything in return (Lk. 6:35).

The nearest we have in Luke to an explanation of the miraculous conception of Jesus is: “The Holy Spirit will come upon (epeleusetai) you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy—the Son of God” (Lk. 1:35). This barely sets Jesus apart as unique—and unique only in the sense that he will fulfil the task given to him (Lk. 3:22), ultimately through his resurrection.

The resurrected Jesus tells his followers: “you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon (epelthontos) you” (Acts 1:8; cf. Lk. 24:28). This rather suggests that the “miracle” of Jesus’ conception was of the same order as the miracles performed by the disciples after Pentecost.

@Andrew Perriman:

Good points.

I wonder how Matthew and Luke squared Jesus being born of a virgin with Jesus being “son of David.”

The fact that Matthew begins with a genealogy establishing Joseph as a descendent of David and has an angel address Joseph as “son of David” makes it doubly confusing that he then removes Joseph from Jesus’ paternity!

@Peter:

The thought occurs that “adoption into kingly succession” was a precedent among the Caesars. Perhaps it didn’t look as strange to the evangelist as it does to us.

A few thoughts:

Re: “First, the “historical” Jesus still impacts the life of the church today—on the one hand, he changed history and we gain from that”

In conversation with a friend of more conventional Christian persuasion, I have suggested (to that person’s dismay) that we ought to read the New Testament not as addressed directly to us, but more along the lines of the way we read the OT prophetic books.

A perhaps less emotionally-disruptive approach would be to suggest that contemporary Jesus-followers should look back to Jesus in ways analogous to how Jesus’ contemporaries in Israel looked back to Moses. They didn’t “personalize” the Exodus, as if Moses had individually led them out of Egypt; nevertheless they had a strong sense of attachment to (perhaps “awareness of” would be better wording) those events that had been so foundational for the creation of their nation and religious community.

–

Re: “The most we can say is that he established a pattern of missional practice for his immediate Jewish disciples for the period leading up to the war against Rome.”

This strikes me as overly pessimistic in terms of the potential applications, within the present-day churches, of Jesus as “exemplary human.”

And “Paul shows no interest in, and little knowledge of, the pattern of Jesus’ earthly ministry” strikes me as simply “wrong”, unless what is being referred to is detailed knowledge of Jesus’ deeds and sayings (but what then does one do with a text like Acts 20:35, which seems to be in in the background of Paul’s thinking in Eph 4:28? Surely Acts 20:35 suggests that Paul had some awareness of Jesus’ sayings and was willing to employ them to lend force to his own teaching. There might be a lot more of this that didn’t make it into the documentary record.)

And Paul points to Jesus again and again as “example” in letters to Gentile churches. Three instances immediately come to mind: 1) Phil 2:5 and following, 2) the appeal for concrete aid that culminates in 2 Cor 8:9, and 3) Eph 5:1-2. And I think that “the example of Jesus” is probably in the background of Paul’s thinking in his numerous commands to his Gentile readers to “one another”-oriented living and to “love and good works”.

It appears to me that “Jesus as exemplar” was a significant factor in Paul’s thinking about the faith communities he founded. And, as we modern believers are the descendants of those communities, it does not seem a huge stretch to me to suppose that there is continuing significance for us, too.

Recent comments