In the six week course I have been doing on “missional church” for King’s School of Theology I have made quite extensive use of the story of Paul’s visit to Athens in Acts 17:16-34 to underline the point that mission in the New Testament is not about the salvation of individuals, it is a call to people groups to align themselves with the God of history.

Missiologists often argue these days that the “missional church” needs to discern and pursue what God is doing out there in the world, but the thought is only developed socially. My argument is that the New Testament is a thoroughly apocalyptic text and that we always have to ask not only what God is doing in space but what he is doing in time. This seems to me a crucial perspective for the Western church when people are seriously wondering whether it has a future. If we take a snapshot of a ball rolling across an open floor, we cannot tell what direction it is moving in. We need movement. We need a trajectory. We need a story.

His spirit is provoked within him

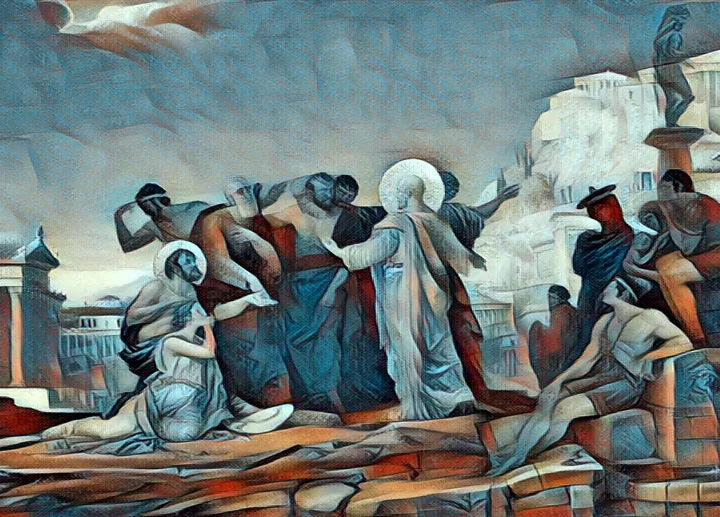

So Paul is alone in Athens, waiting for Silas and Timothy to join him. Luke tells us that as he saw that the city was “full of idols” (kateidōlon), “his spirit was provoked within him” (Acts 17:16).

Remarkably, Livy records that a certain Paulus “went to Athens, which is also replete with ancient glory, but nevertheless has many notable sights, the Acropolis, …and the statues (simulacra) of gods and men—statues notable for every sort of material and artistry” (History of Rome 45.27.11). Strabo likewise notes the prominent visual representation of gods and men in Athens, in the words of Hegesias: “Attica is the possession of the gods, who seized it as a sanctuary for themselves, and of the ancestral heroes” (Strabo, Geography 9.1.16).

It is then because (oun) his spirit is provoked in this way that Paul engages in disputes or discussions in the synagogue with Jews and God-fearing Gentiles (tois sebomenois). Perhaps he wanted to know why, if the Jews of the diaspora claimed to abhor idols, they were accused of robbing temples (Rom. 2:22). Perhaps he was already putting to them his conviction that this civilisation stood under the judgment of YHWH. But the point to grasp is that it is his deeply Jewish—and Jewish-Christian—revulsion at the spectacle of Greek idolatry that sets this story in motion.

The conversation spills over into the marketplace and gains a wider Greek audience—notably, some Epicurean and Stoic philosophers. Luke is not interested in Epicureanism and Stoicism as systems of thought. There is no discussion of pleasure or pain or justice or desire or human flourishing or contentment, or other such matters of philosophical interest. The philosophers merely mistake Paul for a “proclaimer (katangeleus) of foreign divinities—because he was proclaiming as good news (euēngelizeto) Jesus and the resurrection” (Acts 17:18). The narrative function of this little scene is to give him a platform to address the “men of Athens” in order to explain the significance of Jesus and the resurrection (Acts 17:22).

Paul addresses the “men of Athens”

Paul begins by observing that the Athenians are very “superstitious” or “gods-fearing” (deisidaimonesterous). He has in mind the vast number of “religious objects” in the city—shrines, temples, statues, and so on, dedicated or representative of a multitude of pagan divinities or daemons. But he had also come across an altar bearing the inscription “To a god unknown” (agnōstōi theōi)—one of several in the city, it would seem. The second century AD traveller and geographer Pausanias says that in the harbour at Phalerum, along with temples to Athena Sciras and Zeus, there were “altars of gods named Unknown (agnōstōn)” (Description of Greece 1.1.4).

In a similar fashion, though to a different end, Pausanias says that in Athens “among the objects not generally known is an altar to Mercy, of all divinities the most useful in the life of mortals and in the vicissitudes of fortune, but honoured by the Athenians alone among the Greeks” (Description of Greece 1.17). Paul draws attention to an altar to an unknown god; Pausanias advises the traveller to hunt out a little known altar to Eleos, the Greek goddess of mercy. It’s what people did.

Paul then asserts, “What you are worshipping not knowing (agnoountes), this I proclaim to you” (Acts 17:23). The God who made the cosmos does not live in temples made by human hands, nor is he in need that he must be served by human hands. To the contrary, he created humanity to “live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him” (Acts 17:26–27).

There is no “fall” in Luke’s doctrine of creation, interestingly. Rather, distinct nations were created in the expectation that they might grope their way towards God, who was not remote, and find him. Moses tells Israel that they will be scattered among the nations, they will “serve gods of wood and stone, the work of human hands, that neither see, nor hear, nor eat, nor smell,” but “from there you will seek the LORD your God and you will find him, if you search after him with all your heart and with all your soul” (Deut. 4:28-29). Perhaps, then, Paul means only that, against a backdrop of idolatry, Israel uniquely sought after God and found him.

Anyway, he repeats the point that what is divine cannot be thought of as being “like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man” (Acts 17:29), and so we come to the conclusion of his argument. Things are about to change. The true God has overlooked “the times of the not knowing” (tous… chronous tēs agnoias), a period symbolised especially by the presence in Athens of altars to an unknown god, but now he commands people throughout the Greek-Roman world to repent. He has fixed a day when he will judge the oikoumenē in righteousness.

In Luke’s writings, the oikoumenē is invariably, I think, the world governed by Caesar. For example: “In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the oikoumenēn should be registered” (Lk. 2:1); ‘“These men who have turned the oikoumenēn upside down have come here also…, and they are all acting against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus”’ (Acts 17:6–7). This is not a universal or final judgment; it is a regional judgment, in history.

Now at last we get to the point of “Jesus and the resurrection”: God will judge the Greek-Roman world “by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead” (Acts 17:31). What has determined the eventual collapse of this whole political-religious order is the resurrection of Jesus. But this is the means to the greater apocalyptic end. The exalted Jesus, seated at the right hand of God, will be the agent of God’s epochal judgment on the pagan world subject to Caesar.

The idol-worshipping, “gods-fearing” Athenians, for the most part, cannot take the idea of resurrection from the dead seriously, so the proclamation of a coming judgment on their world is a non-starter. Some wanted to hear more, and a handful believed and, in some fashion, joined or perhaps were even baptised into Paul’s brazen, irreligious, apocalyptic movement. The believers would not live to see the historical outcome, the vindication of their faith in the future judgment and rule of Jesus over the peoples of a once pagan world. That is how history often plays out. But the names of two of them at least have been recorded for posterity—Dionysius, seemingly a member of the Athenian council, and a woman called Damaris.

We are obviously not going to tell the same story today. So what story are we to tell? That the God of history, the God of the planet, has fixed a day when he will judge greedy global humanity in righteousness? We can’t say we haven’t been warned.

In the Old Testament we see religious changes mandated by rulers. For example, in the story of Jonah the ruler’s declaration caused the nation to change.

Is it likely Paul believed conversion of the Gentile nations would not succeed without a top-down change, perhaps first governors and then the Emperor?

@Peter:

That’s a very interesting question. Jonah entered Nineveh, made a public proclamation, the people believed God and repented, word reached the king, who issued a decree calling on the population to turn from their evil ways, and God relented (Jon. 3:1-10). Sounds almost too good to be true, doesn’t it?

The apostles also proclaimed the “good news” of coming judgment and regime change in public spaces, and Paul says nothing about getting the message to Caesar or other high ranking officials in his letters, as far as I can recall. But according to Luke, having set out his beliefs before Felix and Festus, and then being accused by King Agrippa of having tried to convert him (Acts 26:28), Paul asks to defend himself before Caesar. Perhaps he intended similarly to present his case before Nero in hope of persuading him to issue a decree calling on all peoples of the empire to repent of their idolatry, violence, injustices, sexual immorality, etc.

Recent comments