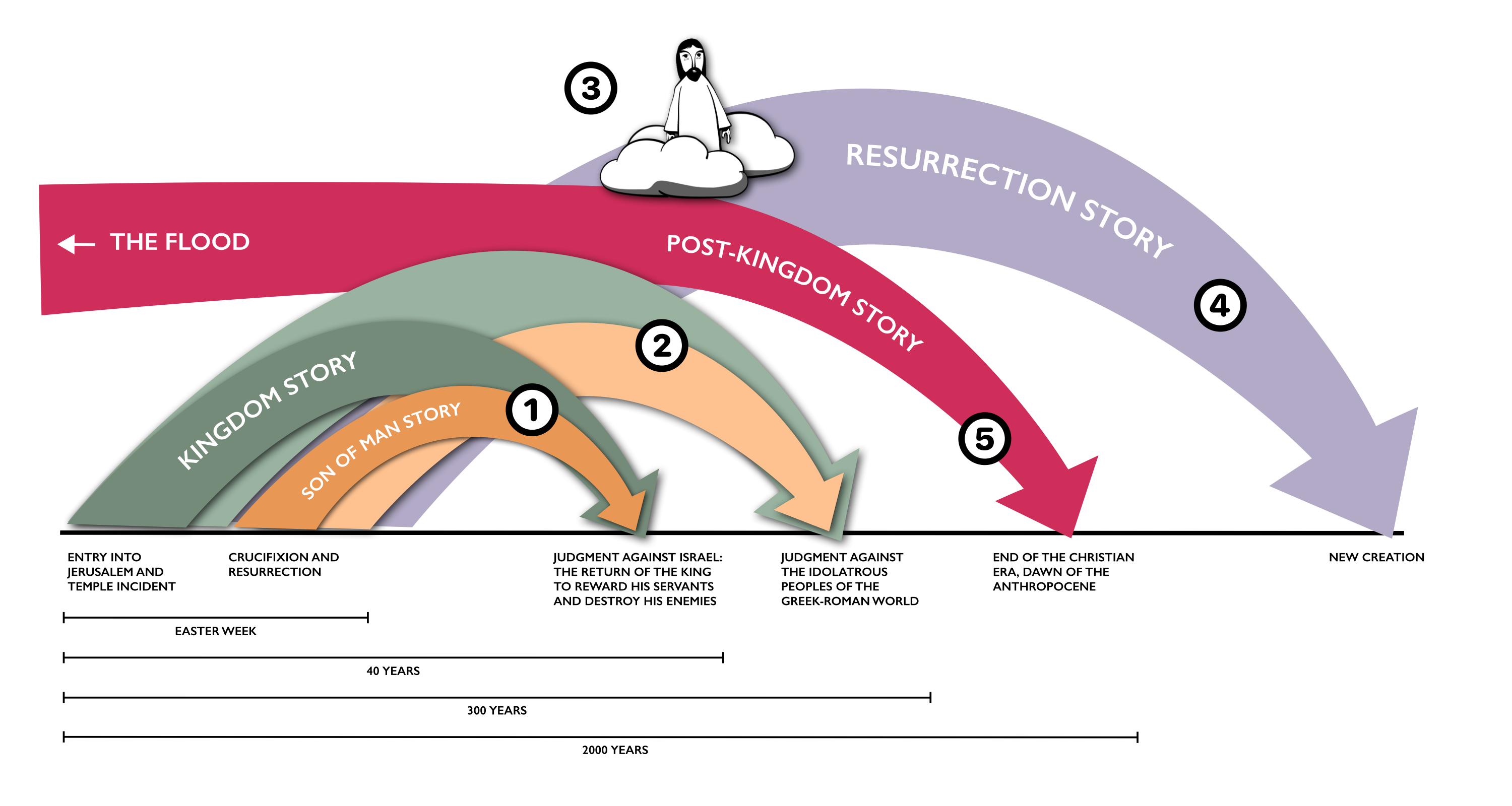

Just for the sake of completeness, here is one final visual representation of the two-part significance of Easter. It’s now getting a bit overloaded, I know—two storylines, four landing points, and an unexpected back-reference to the flood; but I don’t want to give the impression that history has completely exhausted the meaning of Easter.

Well, not just for the sake of completeness. It perhaps also suggests that the church is now located somewhere between “kingdom of God” and “new creation,” which is the tricky narrative space that we need to define if we are going to do justice both to scripture and to history. It’s a vaguely new thought for me that an adapted Adam typology might usefully come into play here. Click on the image for a larger view.

Beyond Easter

1. In the Synoptic Gospels, the public kingdom story will climax in the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and the establishment of a new régime for Israel. The kingdom of God in the Bible is always a political category, having to do with the management of peoples and the interactions between peoples. The insider Son of Man story about suffering, resurrection and vindication defines the means to the overarching kingdom end.

2. In Acts and the rest of the New Testament, the two Easter stories are stretched to encompass the larger fulfilment of the confession of Jesus as Lord by the peoples of the Greek-Roman world, to the glory of the God of Israel (cf. Phil. 2:10-11), who is the God of history. It is the crucified and dishonoured Jesus who will triumph over idolatrous paganism, through the testimony of the persecuted churches, and in the end the churches will share in the public vindication of their Lord. Christendom was the concrete political-religious expression of that triumph, for as long as it lasted.

3. The exalted Son of Man, who came with the clouds of heaven to receive kingdom and power and glory, remains seated at the right hand of God throughout the ages, until the last enemy, death, has been destroyed (1 Cor. 15:20-28). That is the faith of the churches, and it is our guarantee of security, even if it is no longer the confession of the nations.

4. At the outer margins of the prophetic-apocalyptic vision of the New Testament is the conviction that finally all evil, including death, will be eradicated, and there will be a new heaven and a new earth. The resurrection of Jesus is a victory over death and a renewal of life under historical conditions and for historical purposes, but by its nature it is also an anticipation of the final remaking of creation.

5. Where we struggle is in knowing whether the kingdom story still has validity, after the historical fulfilment envisaged in the New Testament. Strictly speaking, I don’t think it does.

I would suggest that in the broadest sense the collapse of Christendom and the rise of a global techno-humanism at the dawn of the Anthropocene must be understood as a development that exceeds the dimensions and scope of the biblical kingdom narratives, for which the only biblical antecedent is the “global” crisis of the flood. We are in transition from a story about God and the nations to a story about God and humanity, beyond politics to anthropology, beyond the fall and rise of empires to planetary disorder.

So it’s anthropology rather than kingdom…

Paul uses the “second Adam” motif to speak about the relation of the one Christ to the many believers: first, the many share in the righteousness of the one (Rom. 5:12-21); secondly, the resurrected many will share in the “spiritual body” of the one (1 Cor. 15:42-49).

I’ve always thought that commentators have tried to do too much with Paul’s so-called Adam christology, with respect to what he was saying either about Christ or about those who are in him. He does not mean that the church is somehow a new humanity in any real sense. The people of God began with Abraham, not with Adam.

But since it is now precisely what it means to be human that is at issue, there is perhaps a third, post-biblical sense in which the motif may be employed. The many must work out how to embody—still under a particular set of historical conditions, not absolutely—the final humanity of the one who was raised from the dead. At least, we must express life and mission in global-existential terms, not in regional-kingdom terms—and yes, we are doing that already, it’s our language that is stuck in the past.

That will not be an easy thing to do. We have anthropological and ethical trajectories in the Bible, but how they are refracted across the complex boundary between the old Christian age and this new, volatile, secular-humanist age is difficult to determine. John’s vision of a new heaven and new earth gives us little in the way of positive content to work with: “death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Rev. 21:4).

We can only redeem from the world in which we live, not some other world. Christendom was Christian Europe. A Christian presence in the Anthropocene will bear many of the marks of the new anthropology, many of the scars of the cultural turmoil through which we are transiting into a largely unknown future, the birth pains of a new and probably quite inhospitable age.

But a redeemed humanity under any circumstances needs to stand out as something different, a plausible sign of the final renewal of all things.

Recent comments