Modern Protestant scholarship identifies three main paradigms for interpreting Paul’s writings: the Reformed, apocalyptic, and New Perspective approaches. The Reformed view emphasizes individual salvation through faith, rooted in Augustine and Luther. The apocalyptic paradigm, championed by Käsemann and Martyn, highlights divine intervention disrupting cosmic evil. The New Perspective, led by Dunn and Wright, situates Paul within first-century Judaism, focusing on Israel’s role and Gentile inclusion. A further Paul-within-Judaism trend deepens Paul’s Jewish identity. Though distinct, these paradigms often overlap. Each offers a different lens—personal, cosmic, or political—raising new questions about Paul’s mission, eschatology, and the historical grounding of Christian theology.

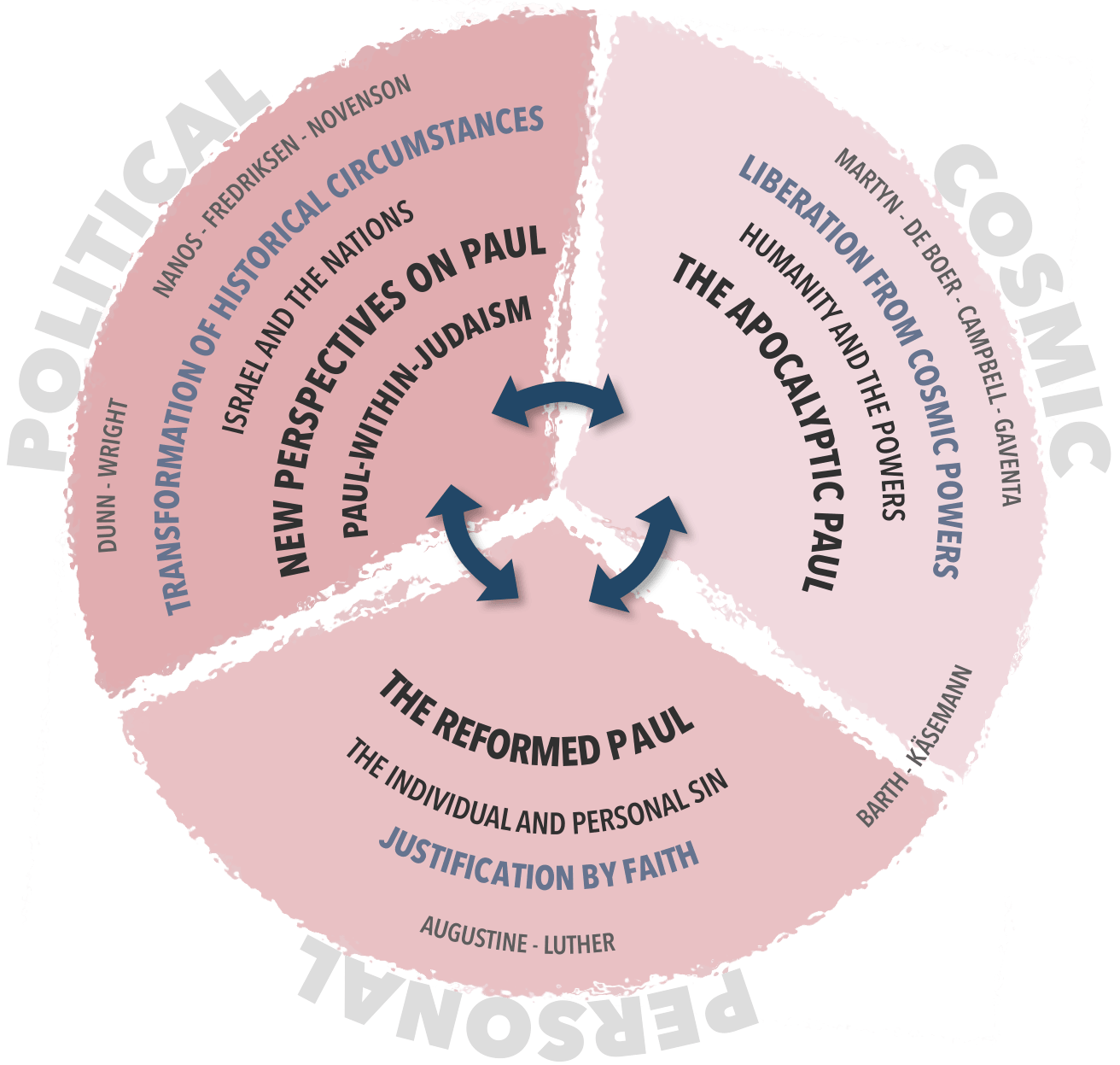

There are three main interpretive paradigms for understanding Paul’s writings available today within mainstream, predominantly Protestant, scholarship. The diagram below names the paradigms, briefly notes the defining characteristics, and mentions some of the major exponents. It also highlights the significance of the boundaries between them. It obviously oversimplifies the picture, and you may disagree with some of the emphases, but it shows rather well, I think, how interpretations of Paul’s “gospel” can be sorted into three obvious categories: the personal, the cosmic, and the political.

The focus of the old Reformed perspective on Paul is on the salvation and sanctification of the individual sinner. Luther is the outstanding representative, but he took inspiration from Augustine: “Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk; he acclaimed Augustine of Hippo as the greatest influence on theology after the Bible.”1 On this reading, Paul gives an account, notably in Romans, of the entanglement of all humans in the sin of Adam and its fatal consequences, the impossibility of pleasing God by the performance of good works, the atoning death of Jesus, the justification of those who have faith, and the new life in Christ, in the power of the Spirit, in the fellowship of the church. Evangelical thought, until fairly recently, has been little more than a popularisation of the Reformed paradigm.

The narrow individualism of the Reformed reading of Paul was “corrected” in rather dramatic fashion, in the second half of the twentieth century, by an emerging apocalyptic perspective. Ernst Käsemann argued that “justification by faith” presupposed a divine incursion in Christ to liberate humanity from enslaving cosmic powers. The thought was developed by scholars such as J. Christiaan Beker, J. Louis Martyn, and Martinus de Boer into a thorough-going and powerful framework for Pauline Interpretation. It still has its advocates today. In her 2024 commentary on Romans, Beverly Gaventa uses the word “intrusion” to define Paul’s gospel in preference Martyn’s “invasion” with its connotations of violence, but the point is the same: “an unexpected event that has its origin elsewhere, enters uninvited, unmakes the world as it is, and produces results that are urgently needed, although they are not entirely welcome.”2

The apocalyptic Paul and the New Perspective on Paul can be viewed as contrasting responses to a problem identified by Weiss and Schweitzer at the end of the nineteenth century. The problem was the prominent expectation of an imminent and catastrophic end—the decisive overthrow of one cosmic order and the inauguration of a new one. Standard theological approaches, whether conservative or liberal, have no way of dealing with this disruptive chaos monster at the heart of the New Testament.

The apocalyptic school took the problem seriously but basically existentialised it, domesticated it, reduced it to not much more than an epistemological crisis. The New Perspective agreed with Weiss and Schweitzer that Paul shared a Jewish-apocalyptic outlook but argued that they had misinterpreted it.

The New Perspective on Paul, associated notably with James D. G. Dunn and N T. Wright, was an initial attempt by scholars with evangelical sympathies to relocate Paul in his first century historical context. What is at stake, fundamentally, is neither the individual’s salvation nor the liberation of humanity from evil cosmic powers but the standing and function of Israel and diaspora Judaism among the nations. Whereas both Reformed interpretation and the apocalyptic Paul are to all intents and purposes Marcionite in their lack of interest in the Old Testament, the New Perspective sets Paul firmly within the whole biblical story—past, present, and future.

Two basic questions are addressed. First, how is God securing the historical future of his people in accordance with the promises made to the patriarchs? Secondly, what is the place of believing gentiles in the “salvation-historical” transition?

This second question, in particular, has provoked the development of a “radical new perspective” on Paul, more often called Paul-within-Judaism. These scholars (I have included Mark Nanos, Paula Fredriksen, and Matthew Novenson) have pushed the apostle further back into his Jewish identity, opening up a gulf between Jewish and gentile “Christianity” that must be explained by some other model than inclusion in a homogeneous community of faith.

I am inclined to think that the Paul-within-Judaism approach is in principle right—at least, we must understand Paul on Jewish terms. But if the supreme—if not absolutely “final”—end in view is the rule of Jesus over the nations of the Greek-Roman world, and if Paul couldn’t be sure about the repentance and salvation of “all Israel,” it may be that covenant continuity is less important to him than the obedient witness of an ad hoc community of eschatological witness to a future that could not be fully comprehended in Jewish terms. What would it mean for Paul’s ecclesiology to be made radically subordinate to or contingent upon his political eschatology?

Finally, we may note that the boundaries between the segments are not rigid or impervious.

In one direction, the work of Barth and Käsemann was a clear attempt to expand the Reformed paradigm. In the other, Reformed scholarship has been willing to embrace some aspects of the New Perspective on Paul.

New Perspective scholars such as N. T. Wright and Katherine Grieb stretch the historical reading of Paul in the direction of the renewal of all creation, and this, for many, has re-energised a personal engagement with his thought.

Some apocalyptic Paul scholars prefer a linear eschatology, which is closer to the outlook of Jewish eschatology, to the “punctiliar” eschatology of J. Louis Martyn. Gaventa doesn’t seem much interested in the New Perspective but she briefly notes that the apocalyptic reading of Romans “complicates” discussion of the Jewish Paul: “it is crucial to understand that this particular Jew has experienced an event and that event has left nothing untouched.”3

We need a creation-level or cosmic framework for mission today, but I don’t think we really find it in Paul. The “event” at the centre of Paul’s thought “left nothing untouched” within the political-religious purview of his mission to Jews and gentiles across the Greek-Roman world. In more immediate terms, evangelical churches need to rethink their doctrinal, liturgical, homiletic, and apologetic engagement with the historical Paul of the new perspectives—as with the historical Jesus.

- 1

Patricia Wilson-Kastner. “On Partaking of the Divine Nature: Luther’s Dependence on Augustine.” Andrews University Seminary Studies (1984), 22.1, 113-24. This quote page 113.

- 2

B. R. Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary (2024), 5.

- 3

Gaventa, Romans, 5.

Recent comments