The limitations of the New Perspective on Paul in its standard form can be illustrated from a piece by Tim Gombis. Tim strongly affirms the New Perspective and nicely expresses his bemusement over the “fear-mongering and hysteria” that the approach has generated in certain quarters. But when you read his summary of the core issues, it is apparent that what we are dealing with is a rather narrowly circumscribed debate about “Paul’s relationship to his Jewish heritage and his discussions related to the Mosaic Law”.

The problem, in the first place, is that Tim appears to view things primarily through the lens of Galatians, where the question of whether Gentiles need concretely to identify themselves with Law-based Israel by means of circumcision, etc., is very much at the forefront. This is a specific issue, however, occasioned by the activity of Judaizing apostles from Jerusalem. What are the markers of authentic membership of the people of God? Works of the Spirit or those particular “works of the Law” that demarcate Jews from Gentiles (Gal. 3:5)?

Romans, on the other hand, addresses the issue of “works of the Law” on a much broader and logically prior basis. Here the premise of Paul’s argument is that a “day of wrath” is coming upon the ancient world. This will bring a dramatic and decisive end to the whole system of pagan religion and ethics; and Israel, despite having the Law and a bunch of other privileges, will not be exempt from “judgment”. Judgment means destruction (Rom. 9:22). So the critical question is not about membership but about survival. On what basis will the “righteous” live when the day of wrath comes (cf. Hab. 2:4)? Not on the basis of “works of the Law”, because the Law now condemns, but on the basis of a radical faith—which is also faithfulness—in the story of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

So the New Perspective, as Tim Gombis presents it, is limited in the first place by its failure to grasp the historical-eschatological dimensions of Paul’s thought. Tim cites the generalized Christian apocalypticism of scholars such as J. C. Beker, Lou Martyn, Bruce Longenecker, Douglas Campbell, and Leander Keck. But I think that Paul’s apocalypticism is much more focused, contingent, historical and, indeed, Jewish—and that his argument about Law and faith in Romans 2-4 cannot be properly understood without taking this narrative of wrath into account.

Tim writes that the “incarnation is the invasion of the Son of God to retake God’s world for God’s glory”. I would say that the resurrection of Jesus is for Paul a clear indication that the God of Israel intends to annex the Greek-Roman world for the sake of his glory. I think that Paul lies quite a bit further outside the sphere of a theology shaped by the western Christendom-modern paradigm.

This brings us to the second limitation, which is highlighted by this paragraph:

Several scholars have complained that the “new perspective” can tend merely to describe Paul’s flow of thought sociologically so that we’re left with a very thin theological reading of Paul. This criticism isn’t too far from the mark. I agree with Stephen Westerholm’s point that while “new perspective” scholars may outstrip the reformers in grasping historically what Paul was getting at, they cannot match the reformers at recovering Paul’s deeper theological impulses. Interpreters such as Augustine, Luther, and Calvin do indeed provide for us excellent models of theological interpretation of Paul.

The word “sociologically” is wrong. Paul’s argument remains thoroughly theological even when located within its own historical-eschatological setting, for the reason that I gave above: it is not merely a matter of the terms of membership in the covenant community; it has to do with the agenda of Israel’s God. But the criticism is correct: we have not yet worked out how to derive from the re-contextualized Paul a theology compelling enough to drive and sustain the life and thought of the church today.

The answer to this dilemma, however, cannot be that we simply bolt a Reformation theology on to the New Perspective. Tim Gombis seems to want to both have his cake and eat it. These are incompatible paradigms. The distinction between what Paul meant historically and his “deeper theological impulses” is an invalid one. We only have the historical Paul.

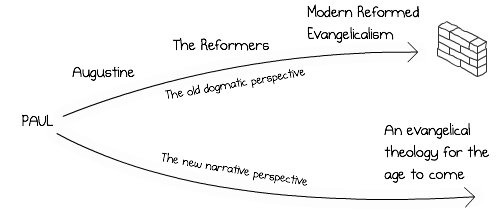

Instead, we have to take the much more difficult approach of plotting a new theological trajectory from a consistent New Perspective reading of Paul to land somewhere beyond the modalities of Christendom—remember that the Reformation was only an attempt to reform the Christendom model of church. If the insights of the Reformers or of modern evangelicalism then help us to understand more clearly what it means to have been brought into this narrative, fine. The same could be said of any other Christendom tradition. But Paul has first to be allowed to speak for himself.

Thanks, Andrew, for giving attention to my post. Just a few points by way of response:

First, I did not intend to summarize the core issues of the New Perspective, but rather, in light of the close of that era in Pauline studies to list a few “generalized aspects to my reading of Paul, especially where his discussions regarding the Law are in view.”

Second, I can’t discern where we disagree over “works of law.” My target here is the interpretive angle of approach that regards the phrase as Paul’s shorthand for “legalism.” I think this is untenable and probably the central insight of the New Perspective. My only point is that the phrase indicates deeds done that constitute Jewish identity. While Paul doesn’t criticize being Jewish per se, he states that merely being Jewish is no guarantee of escape from God’s judgment and participation in the world to come. I do need to check out your book on Romans (my stack of “must-reads” is growing in light of our summer move!), but on this issue I don’t see any distance between us.

Third, by mentioning the incarnation of Jesus, I did not intend to displace his resurrection nor to place Paul within a Western Christendom-Modern paradigm. Can’t say everything about Paul’s theology in one blog post!

Fourth, I am advocating anything but bolting a Reformation theology to the New Perspective. Far from it! I’m still struggling (and am a bit horrified, actually!) to see how you’ve read me to advocate this...

I only cite Westerholm to indicate that some early New Perspective readings weren’t entirely satisfying theologically. I only claim that the reformers were doing theological interpretation of Paul for their day. Please read this mild commendation of the reformers for what it is, and not as a wholesale endorsement of Christendom or Reformation theology.

My final paragraph indicates, I hope, where I’m headed with this. I do hope that the New Perspective era served mainly as a ground-clearing exercise for fresh readings of Paul. It seems shocking to even think it, in light of all that’s been said and written about Paul, but there are profound theological resources in Paul—the very ones you indicate—that remain untapped. The hijacking of the apostle by reformed theologies has misdirected our search and I find the way of promise in reading Paul himself, as you do. It seems clear that we agree on this!

Cheers, Andrew!

tg

Tim, thank you for taking the trouble to respond.

1. Fair enough. But my impression is that the New Perspective has tended to be preoccupied with a fairly narrow set of issues centring on the question of Jewish identity and the grounds for participation in the community—and in the concluding paragraph of the original post you stated that ‘the “new perspective” has been very helpful in reminding us that the problems of ethnicity are at the center of Romans and Galatians’. In your view, to what extent do the “core issues” of the New Perspective extend beyond your reading of Paul and the Law?

2. I maybe misunderstanding something here, but I think I would disagree that the phrase “works of law” only “indicates deeds done that constitute Jewish identity”. Here I would side with the Reformed criticism of the New Perspective. I think Paul is very much concerned about the concrete works of righteousness that should flow from a right relationship with the creator God. I don’t think that he is primarily criticizing Jews for a complacent reliance on being Jewish, though that thought is clearly present. His core argument is that Israel has not lived up to the standards of the Law and for that reason has come under condemnation. This is not about legalism as a way of salvation. In Romans it has to do with the grounds on which Israel’s God will judge the pagan world.

3. I generally think that the resurrection of Jesus is much more important for Paul’s thought than the incarnation. In Romans 1:4 “Son of God” speaks of resurrection rather than of incarnation. Indeed, it’s a little questionable whether Paul even has a doctrine of incarnation. But my more substantial point was the contrast between retaking the world and annexing the Greek-Roman oikoumenē. I think that Paul’s apocalyptic outlook was rather more circumscribed than the standard New Perspective interpretation allows.

4. I’m horrified to think that I might have horrified you! It seems I got hold of the wrong end of the stick here. It did actually occur to me that you might be using Westerholm only to highlight a shortcoming of New Perspective readings, but the statement “Interpreters such as Augustine, Luther, and Calvin do indeed provide for us excellent models of theological interpretation of Paul” seemed a rather forceful endorsement of Reformed theology as a way of getting at the heart of Paul’s thought. Apologies.

Yes, we agree about the hijacking of the apostle.

@Andrew Perriman:

Ready to respond, Andrew, after driving all over creation the last few days. We're in the midst of a move...

1. It seems to me that Reformed readings of Paul, especially Romans & Galatians, had straight-jacketed Paul so that everything he had to say revolved around abstracted theological notions tied up with heavenly legal transactions. So much else of what Paul said was either swept under the rug or muffled in the interests of maintaining these readings. NPP readings broke this stranglehold so that now Paul can be read aright. It seems to me that reading Paul can go in lots of different directions, including a few of the basic "reformed" concerns of Paul's rebuke of anthropological optimism. It's tough to talk about generalities viz. Paul without talking about texts, which I hope to get to once we're settled.

2. On "works of law," this may be the case in contexts where this phrase is used, but it seems to me that the bare phrase indicates Jewish identity and only that. As to what Paul says in contexts in which he utilizes this phrase, well, that gets down to actually digging into texts and grappling over how he employs the phrase.

3. I sort of agree here, though we may be talking in different directions. To my mind, this is where the NPP comes to an end and ceases making its contribution. It only was a deck-clearing exercise. Regarding a robust description of the place of the resurrection for Paul, the NPP simply is silent. No contribution at all, really.

4. In commending historical figures, I partly wanted to throw a sop to my Reformed friends, but also to place these figures historically. They can serve as a model of theological interpretation, reading Scripture for their day, but leave them there. In theologizing today, we go back to Paul himself, reading him as Scripture and reading him as a reader of Scripture, drawing upon Pauline resources for our day. On that note, I agree with Wright that we stand on the reformers' shoulders, we don't parrot their theologies.

Andrew, I cannot tell you how timely this post was. I was in the process of writing a response to the most recent Mark Driscoll debacle (a recent twitter comment he posted emasculating certain types of praise and worship leaders) when I came across your post. (by the way, here's a good post on the Driscoll debacle if you haven't read it).

What folks maybe now can begin to understand about Driscoll and the new Reformed movement is that its identity is probably as wrapped up in conservative complementarianism as it is in Calvinism. The patriarchal attitudes woven into the theology, the male-drivenness of the movement is overwhelming. This is why, as you said, it “cannot be that we simply bolt a Reformation theology on to the New Perspective. Instead, we have to take the much more difficult approach of plotting a new theological trajectory from a consistent New Perspective reading of Paul to land somewhere BEYOND (my caps) the modalities of Christendom—remember that the Reformation was only an attempt to reform the Christendom model of church”. Yes and a hearty “amen".

@Jim :

Honestly I think the reaction to Driscoll is more than a little over the top. Yes, his views are annoying, but there are far more important issues that we could be writing letters about and spending our time on. There are a thousand equally misguided 'pastors' out there, they just aren't quite so good at publicising themselves. Furthermore, it is pretty naive to think that writing to the elders of a church made up primarily of people who go there because they like Driscoll and what he stands for is going to persuade them to get rid of him (if they even can, from what I hear he has got a pretty closed system going on). Why not spend the time instead talking to a homeless person or your elderly next door neighbour? Or if you really want to write a letter, write to the advertising standards authority and national fraud strategic authority about the con artists making millions on the God channel.

@Rob:

Thought I'd better mention as misunderstandings are unfortunately common in the bloggersphere, by 'you' and 'your' I don't mean you personally Jim - I was making a general not a personal comment :-)

@Rob:

I get you, and no doubt Driscoll will probably remain unaffected and dogmatic in his viewpoints. But something else may be happening on a grassroots level. Women are stepping up, beginning to bring a shift, not only by taking their place, but dealing with the the bully ethos that permeates both secular and evangelical culture.

In my view this is not a small, irrelevant, religious adjustment, or a tweak, or a stronger pull of some previously used lever. Those moves were akin to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. No, I think this might be different (and I could very well be wrong) but we might well be at another essential, another memorable theological tipping point....they can appear suddenly, in unexpected ways, through unexpected agents of change.

Per the Oxford Dictionary of the English language the word "jew" first appeared in print in 1775 AD.

Jesus indeed was not a "jew" because the word did not exist prior to 1775. Why do otherwise apparently highly educated deep thinkers contintue to insist on applying this word "jew" to Christ when the word did not exist till 1700+ years after His era?

I insist that the natural result of this lie that Jesus was a jew when He was not, is to promote and elevate Rabbinical Talmudism (modern Judasim) over and above Christ and His teachings. In effect, use of the word "jew" elevates the Rabbi murderers of Christ over and above Christ.

Another form of such lying language is the term "Judeo-Christian", the word "judeo" not appearing in Scripture, and again, confusing Christ with His murderers. John MacArthur's study Bible is more of the same. MacArthur's narrative of Rev 2:9 and 3:9 states that jews who do not proclaim Christ are not true jews, implying the lie that Christians are fulfilled jews, rather than proclaiming the truth, being that jews are followers of Rabbinical Talmudism, and therby spiritual sons of the devil.

I desire no violence or phsyical retribution against modern physical jews nor anyone else, only the ekklesia to stop using language elevating the Rabbis over and above Christ who they killed.

@Joseph Jones:

Joseph, this seems to me to be nonsensical and probably anti-semitic. When the term “Jew” appeared in the English language is neither here nor there; I fail to see what any of this has to do with promoting Rabbinical Talmudism; it was the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem under Pontius Pilate who arranged to have Jesus executed, not Rabbinic Talmudism; and the term “lying language” is unnecessarily offensive. Jesus, like Paul, was an “Israelite” by race and flesh (Rom. 9:4-5).

I don’t, in any case, see how your comments relate to the theme of the post and I will delete any further comments that make use of this thread, or any other, to pursue an irrelevant agenda.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew's words in quotes followed by my reply:

"Joseph, this seems to me to be nonsensical and probably anti-semitic."

Yes, I'm quite famililar that everyone who points out that modern Judaism is Rabbinical Talmudism and the Talmud states Jesus boils in excrement for eternity is immediately labeled an anti-semite.

"When the term “Jew” appeared in the English language is neither here nor there"

So says Andrew. Let's see, the word Jew did not exist in Jesus and Paul's lifetime, yet it's accurate to label Jesus and Paul "Jews". How is that, Andrew? Should we call Jesus "Pantera" because that is the modern Judaic/Talmudic term for Jesus, being the name of Jesus' alleged Roman guard father? Do you think I'm making this up? It's well documented by the Judaic Christian Michael Hoffman in Judaism Discovered.

"I fail to see what any of this has to do with promoting Rabbinical Talmudism"

When you call Jesus a Jew, you equate him with modern Judaism, whose holliest of all holy books is the Talmud written by the heirs of Christ's murdering Rabbis. Is that a distant connection?

"it was the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem under Pontius Pilate who arranged to have Jesus executed, not Rabbinic Talmudism"

Your choice of the verb "arranged" is quite wrong. Do you deny the stark, blatant verb "killed" in 1 Thes 2:14-15 "...the Jews who both killed the Lord Jesus and their own prophets..." It's a common Talmudic practice to deny the Israelites committed the worst crime in mankind's history, the murder of the innocent Christ.

Oh, and exactly what's the difference between the Rabbis who murdered Christ and modern Rabbis who slander Christ relentlessly, the ones who say Jesus got exactly what he desereved and they'd do it again? You demonstrate my point well. Modern so-called Christianity shares much with Talmudism.

"and the term “lying language” is unnecessarily offensive."

If Jesus was not a Jew (argue with Oxford about that, not me) because the word Jew did not exist till 1740 years later, it's either a lie or naitivity to call Jesus a Jew. If it's naitivity, I sincerely apologize for the language. Is it too much to request the error be acknowledged and corrected?

"Jesus, like Paul, was an “Israelite” by race and flesh" (Rom. 9:4-5).

I obviously agree that Jesus and Paul were Israelites. Do you just ignore the point that modern Jews never known as Israelites, but rather Israelis, a term unknown in Scripture? I do not know about Biblical use of the word "race" associated with Israelites, though I know Christians commonly say there was and is a Hebrew "race".

But was Jesus a "Jew" or was Jesus not a Jew?

"I don’t, in any case, see how your comments relate to the theme of the post and I will delete any further comments that make use of this thread, or any other, to pursue an irrelevant agenda."

Attempting to label Christ a Jew is misleading and incorrect. It elevates modern Rabbinical Talmudism because that's what Judaism is based on, and detracts from Christ's majesty and glory. That's always a bad thing, including in the original article which labels Christ a Jew.

Recent comments