In his new book The King Jesus Gospel: The Original Good News Revisited Scot McKnight starts out by arguing that the “gospel” has to be distinguished from the “plan of salvation” that lies at the heart of modern evangelical theology and preaching. The gospel is not a formula for personal salvation; rather it belongs to “the Story of Jesus as the resolution of Israel’s Story” (44). Only once we get this difference sorted out will it become possible to ‘develop a “salvation culture” that finds its only true home in a “gospel culture”. The urgency of this correction lies in the fact that only a “gospel culture”, in Scot’s view, can inform and sustain discipleship.

There are actually, I think, two important distinctions at play here. The first is between “gospel” as we find the term used in the New Testament and the supposed “plan of salvation”, which most people today unthinkingly confuse with the gospel.

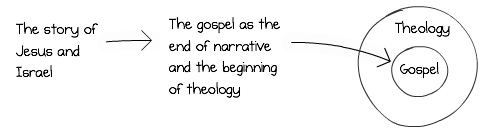

The second is between narrative as the proper setting for “gospel” in the New Testament and the more “abstract, propositional, logical, rational, and philosophical” way of doing theology (62) in which the “plan of salvation” finds its home:

Because the “gospel” is the Story of Jesus that fulfills, completes, and resolves Israel’s Story, we dare not permit the gospel to collapse the abstract, de-storified points in the Plan of Salvation. (51)

I agree with both these distinctions, but I fear (I am only part way through the book) that Scot will truncate the narrative structure of New Testament thought prematurely. The problem lies in the argument that Jesus completes Israel’s story, because what it gives with one hand, it takes away with the other: it is an argument both for narrative and for the termination of narrative.

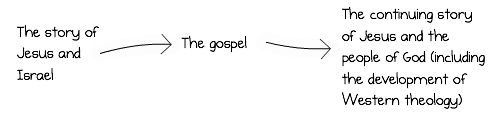

I will try to explain this perhaps rather difficult contention by setting out three ways of framing the idea of “gospel”. The first is the traditional approach, which Scot rejects. The second is Scot’s own position, at least as I understand it; and it is a substantial improvement on the traditional view. It is also, I think, Tom Wright’s position—not surprisingly, since Scot openly draws on Wright’s understanding of the gospel as “the narrative proclamation of King Jesus”. The third position is a consistent narrative-historical approach to understanding how “gospel” functions in the New Testament. I think that Scot, like Wright, moves things in the right direction but doesn’t go far enough.

The theological gospel

Modern Reformed and Evangelical theologies have mostly forgotten their narrative-historical origins. They have been profoundly shaped by a European intellectual tradition that is not comfortable with truth until it has been rationalised—and “de-storified”—to the point of abstract universal application. So theological truth is a plateau, elevated above the surrounding plain of human knowledge by revelation, but open to exploration and mapping. The “plan of salvation” theology of which Scot is rightly critical is one rudimentary way of mapping this landscape.

The gospel between history and theology

The recognition that Jesus—and the gospel about Jesus—cannot be properly understood apart from the story of Israel has changed this picture, but only to a limited degree. We have begun to grasp the fact that our theology has its origins in a journey along the narrow ravine of Israel’s history. But the “completion of the story in Jesus” model carries the implication that this is an upward journey and that eventually we arrive at the top of the ravine of Israel’s story and find ourselves on the level ground of a plateau. Paul then represents the point at which the narrative about Israel gets translated into a story of universal salvation, which then becomes the stuff of European or Western theology.

So it is not simply the story of Israel that terminates here. The whole narrative construction of the self-understanding of the people of God comes to an abrupt halt and is replaced by a generalized theological definition. Jesus brings Israel’s story to a climax, and then becomes the saviour of mankind. Gospel as an announcement about the completion of Israel’s story gives way to a plan of salvation. The thought of the concrete, limited existence of a chosen people in covenant relationship with the creator, in the midst of the nations, gives way to a universal religious option predicated on the need for personal salvation.

The historical gospel

This shift from history to theology certainly happened—for better or for worse. But I don’t think it happened with Paul. Paul set out to claim the Greek-Roman world for the God of Israel, who had raised Jesus from the dead—a thoroughly political undertaking—but he did so as a Jew, not as a proto-European Christian.

So Scot is right to highlight the illogicality and bias of John Piper’s question, “Did Jesus preach Paul’s gospel?” “Isn’t the more important question,” Scot asks, “about whether Paul preached Jesus’ gospel?” (25). But it’s not just a matter of whether Paul preached Jesus’ gospel. It’s a question of whether Paul shared Jesus’ whole mindset about the historical and narratively constructed existence of the people.

The central categories of Paul’s theology—wrath, gospel, salvation, justification, faithfulness, suffering, righteousness, parousia—are historically determined. They cannot be understood apart from a projected but realistic story about the future of the churches in Asia Minor and Europe—any more than Jesus’ gospel regarding the coming kingdom of God can be separated from the story of Israel in crisis. They all presuppose decisive future events through which the persecuted churches would be delivered from their enemies, vindicated for their faith in Jesus, and the one true God would be shown to be right in the eyes of the nations.

What Paul announces is not so much the completion of Israel’s story in Jesus as the continuation of the story of the people of God under Jesus. The story has a future, and it is not so different in kind from the story that led up to Jesus.

To put it slightly differently, the story that is completed is the story of Israel and the nations, and this cannot be understood as a simple termination. On the one hand, it is only preemptively completed in Jesus: it still needs to be worked out historically, through a narrative of crisis and suffering that will culminate in the conversion of the empire to the worship of YHWH and of his Son. On the other, even this momentous event is not the end of history for the people of God. The progressive marginalization of the church since the Enlightenment has served to remind us that we are a people subject to the vicissitudes of history, not merely proponents of abstract theological truth.

I suspect that this realization goes some way towards explaining our attraction to the idea of the gospel as the “narrative proclamation of King Jesus”. But I think that we need to have the courage of our narrative-historical convictions and follow the argument through, not pull up short when we get to Paul.

Scot does clarify, I think, that he is using the term "completes" in a way that views the narrative as an ongoing reality. I will try to find the reference when I get home, but he is careful to note he does not mean Jesus "completes" Israel's story in the sense of "termination"...

@Ben T.:

The good news from God to me, a Gentile, is that as a sinner under His wrath, Jesus Christ bore my sin, not in part but the whole, on the Cross, and in His death. He rose from the dead three days later, and He sought me, since He bought me. I am one of His sheep, that the Great Shepherd brought into His fold; a fold of Jews and Gentiles.

What a Savior and a Shepherd and a Lamb of God slain before the foundation of the world! he is the good news, the way, the truth, and the life!

I like Scot, but he and I seem to see the things of Scripture different. Look forward to be with Scot in the new universe, and then see how wrong we both were, and how right we both were. And we are both right on trusting in Christ alone, through grace alone, by faith alone.

@Ben T.:

Thanks, Ben. I’ll keep a lookout for the thought. I have a bad habit of jumping to conclusions—it comes from having read too many books, I think. I’d hate to do Scot a disservice.

Still, I think the general point remains true, that there is a version of the argument out there that loses narrative momentum when it gets to Paul. I think it is evident in the fact that many will read Mark 13 historically (destruction of Jerusalem as vindication of the Son of man) but not 1 Thessalonians 4. At least, I think we greatly underestimate the importance of an prophetic narrative for understanding Paul’s thought—even in a very theological Letter such as Romans.

Michael,

This is a fair and good pushback, but I do think I'm with BenT on this one and it may simply not be clear enough in this book. I was nervous about the word "completion" and would have used "fulfil" if I thought it made more sense... but for me "completion" doesn't mean "story over" but story reached its defining point now for the rest of this chp until consummation.

And Blue Parakeet did this even better: we are in, to use Tom's categories, chp 5 of the Story now.

But this point needs pushback or fuller clarification because I'd not want folks to think it's all over but the handshake.

@Scot McKnight:

Michael?

Helpful clarification, though. Thanks.

Andrew, it seems that "climax" is a central category for Wright's articulation. How does climax as a narrative category sit with you? Climax is not synonymous with resolution by any means and necessarily implies an ongoing story. But perhaps is claims too much for a particular historical moment from your perspective?

Greg, good thought. “Climax” does it for me, as long as it doesn’t make everything that follows merely an anticlimax. I think, actually, the important question then is: What story is it the climax too? Wright tends to make it the climax to a redemptive narrative. Scot may do the same. But it seems to me that the central narrative regarding Israel actually culminates in the triumph of YHWH over the idolatrous nations. This does not happen apart from the redemption of Israel and then the inclusion of Gentiles in that redeemed people. But this is the significance of Psalms 2 and 110 for Paul’s account of his gospel. We would normally project these ambitions into a remote and final future, but I suspect that Paul understood them in much more immediate, historical terms.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

I hope this isn't too off-topic, but I was curious about your eschatology, and specifically if you'd identify most with an amillennial or postmillennial position? I ask because I have pretty recently become "postmil" in inclination - meaning I think the church has a very positive future in this world before the final resurrection and judgment, and that perspective has in turn made me more inclined to the kind of continuing-narrative theology you describe in this post as opposed to the more flattened and abstract system Evangelicalism seems to have these days. For those who are amillennial and think the final coming of Christ, resurrection and judgment could happen any minute, the (perhaps subconcious) implication is that there really is no more significance to history, and flatter and more abstract systemization of things is the fallout.

@Daniel H.:

Daniel, I agree that the church has a very positive and constructive future, but I would account for this in the first place in terms of an eschatology of new creation: the purpose of the people of God has always been to embody in its communal life and for the sake of the nations the possibility of new creation. The church proleptically brings the new heavens and the new earth into the present, both as sign and reality.

I understand the thousand year reign of Christ and the martyrs to refer symbolically to the period of time between the overthrow of Rome as aggressive, idolatrous empire and the final judgment of all the dead and remaking of all things. John’s dominant eschatological horizon is the judgment on Rome. What ensues is marginal to his purposes and is depicted in scanty symbolic detail.

I should add that I think that much of “second coming” material relates to this historical moment, when the persecuted churches will be delivered from their enemies and vindicated for having put their faith in Jesus as the one through whom YHWH would turn the ancient world upside down.

Andrew,

Good thoughts. Something I have been working on for awhile. Here's what I would highlight in your post: "Paul then represents the point at which the narrative about Israel gets translated into a story of universal salvation, which then becomes the stuff of European or Western theology." Might we use the word, "proleptic" (J.C. Beker)? Second, "What Paul announces is not so much the completion of Israel’s story in Jesus as the continuation of the story of the people of God under Jesus. The story has a future, and it is not so different in kind from the story that led up to Jesus." For Paul, I believe, "fulfillment" involves "durative" action (realization by progression), rather than "punctilliar" action (a single event). Make sense?

You realize that I don’t approve of the fact that Paul is taken to stand for a generalized, a-historical theology?

You can certainly use the word “proleptic”. I use it in a comment above: “The church proleptically brings the new heavens and the new earth into the present, both as sign and reality.”

For Paul, I believe, “fulfillment” involves “durative” action (realization by progression), rather than “punctilliar” action (a single event).

It makes sense—but how would you show that it’s actually true for Paul?

Scot wrote:

"I was nervous about the word 'completion' and would have used 'fulfil' if I thought it made more sense… but for me “completion” doesn’t mean “story over” but story reached its defining point now for the rest of this chp until consummation."

Perhaps a phrase from many a good Hollywood movie fits?

...to be continued...

Recent comments