It just so happened that having finished the post on Justification with reference to Wright, Gorman and Campbell, I had an email from a friend at Regent College asking what I thought of Stephen Westerholm’s critique of the New Perspective in a CTQ article from 2006 entitled “Justification by Faith is the Answer: What is the Question?”1 Well, it wasn’t what I was planning to do today, but it’s all in a good cause—so, Barney, here is roughly what I think.

Westerholm sets out two quite distinct positions on the question of “justification by faith”. He oversimplifies on both sides, but the clarity is helpful.

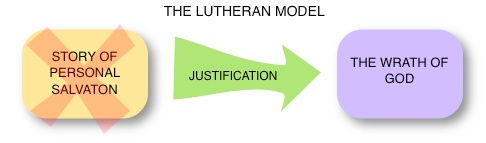

1. The traditional Augustinian and Lutheran view has been that Paul’s doctrine of “justification by faith” is intended to answer the question: “How can a sinner find a gracious God?” This is essentially an existential and universal issue. For the Jews the Law was only a stop-gap measure until Christ; for everyone else it represented a universal tendency towards self-justification through works.

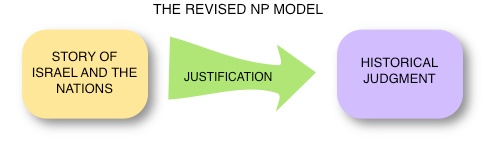

2. The New Perspective holds that “justification by faith” is Paul’s answer, rather, to the question: “On what terms can Gentiles gain entrance to the people of God?” In this case, the issue has been framed covenantally and historically. The following catena of quotes from the major New Perspective prophets puts the case in good Pauline fashion (198-200):

The first issue at hand is whether Paul intended his argument about justification to answer the question: ‘How am I, Paul, to understand the place in the plan of God of my mission to the Gentiles, and how am I to defend the rights of the Gentiles to participate in God’s promises?’ or, if he intended it to answer the question, which I consider later and western: ‘How am I to find a gracious God?” (Stendahl)

The question is not about how many good deeds an individual must present before God to be declared righteous at the judgment, but, to repeat, whether or not Paul’s Gentile converts must accept the Jewish law in order to enter the people of God or to be counted truly members. (Sanders)

The leading edge of Paul’s theological thinking was the conviction that God’s purpose embraced Gentile as well as Jew, not the question of how a guilty man might find a gracious God.” (Dunn)

[Israel] was determined to have her covenant membership demarcated by works of Torah, that is, by the things that kept that membership confined to Jews and Jews only. (Wright)

Westerholm neatly sums up the controversy:

Did he mean that faith alone, not the observance of distinctively Jewish works of the law, is required for Gentiles to be included in the people of God? Or was his point that sinners are declared righteous by faith alone, apart from the righteous deeds that the law requires? Justification by faith is the answer, but what is the question? (200)

Westerholm considers a number of passages beginning with Ephesians and the Pastorals and working backwards through the Letters to Thessalonica and Corinth to Galatians, Romans and Philippians, with a detour via James along the way. He draws the conclusion that for the most part Paul’s focus is on the problem of sinners facing the wrath of God, men and women who are perishing, who cannot be saved by “good works”—not merely works of covenant membership—and who therefore need to find a gracious God.

The problem, I think, is that while the argument about perishing sinners needing to find a gracious God can be educed from the New Testament, it remains a theological abstraction. The process of abstraction has obscured the fact that the various pieces from which the thesis has been constructed all presuppose a covenantal and historical narrative. Wrath is not a final or absolute category in scripture: it defines historical events of massive covenantal significance—military invasion, the defeat of Israel’s imperializing oppressors. Sin is historically contextualized: the Jews are “sinners” because they have rebelled against YHWH; the Greeks are sinners because they have exchanged the glory of the creator for worthless idols. The general fallenness of humanity in Adam is an issue because it has vitiated the particular calling of Israel to embody the righteousness of YHWH. When Paul says that “by works of the Law no flesh will be justified before him” (Rom. 3:20), he is not asserting a universal principle, as Westerholm would have it (214): his point is that those who are “under the Law” (ie. Israel) must be held accountable in order that the world may be held accountable (3:19). The narrative background to his argument throughout is the crisis of Israel’s failed witness and the emerging prospect, in spite of that, that YHWH will be vindicated in the eyes of the nations. He does not step outside this corporate-historical trajectory in order to develop a separate a-historical theology of personal justification.

To take just one simple and unlikely example, Westerholm cites 2 Timothy 1:9 as evidence that salvation has little to do with the entrance requirements for Gentiles to enter the covenant community: God “saved us… not because of our works but because of his own purpose and grace”. That looks like a classic Protestant formulation. But even in this personal letter there are clear indications that this salvation cannot be separated from a wider narrative about Paul’s apostolic mission that will culminate in a “day” of reckoning. The narrative is only there in outline, but how is it to be filled in? There is still good reason to think that what we have here is an argument about the salvation of the covenant people, not on the basis of any works of the Law but through the appearance of Israel’s messiah—with all that that language implies. Whether or not “justification” determines the ground for inclusion of Gentiles in the people of God, it certainly belongs to—and should remain as part of—a story for which this was a central issue.

One of the things that makes Westerholm’s critique superficially plausible is the fact that the New Perspective has dissociated the issue of covenant membership from any sort of realistic conception of divine wrath. Covenant membership is taken to be a historical matter; divine wrath is assumed to kick in only at the end of history. Wrath is not, generally speaking, directed against individuals, and certainly not in a final judgment: it is directed against nations and cultures—in particular, against Israel and the enemies of Israel. Indeed, I would go as far as to suggest that it is only when we grasp this diachronic framework that the New Perspective argument about covenant gains any theological traction.

So it seems to me that the standard New Perspective account is right insofar as it stresses the corporate-narrative dimension to the issue of justification but wrong in trying to make the argument work apart from the prospect of imminent eschatological crisis.

Conversely, Westerholm is correct in highlighting the wrath of God against sinners but wrong in abstracting this from the historical narrative about the survival, transformation and vindication of the people within a foreseeable timeframe.

But if we disconnect both positions from a final eschatology and attach them to a proximate historical eschatology, they fit together rather well.

The question to which “justification by faith” is the answer, therefore, is something like: How can the people of God survive the “wrath” that is coming first on Israel, then on an antagonistic pagan world? The people of God will not be preserved by works of the Law because the Law has finally condemned national Israel to destruction. Gentiles outside the people of God may well do good works, and they may count themselves justified on that account when this judgment comes (Rom. 2:13-16). But that community of Jews and Gentiles that is called to embody in itself the righteousness, the vindication, of God will come through the crisis and stand—symbolically speaking—unashamed before the judgment seat of Christ only if it exercises the radical trust that Jesus demonstrated in his suffering and death.

Faith is important in Paul’s argument not primarily as the basis for membership in the covenant people but as the stance necessary for the “elect” to survive the coming wrath of God and be vindicated. This is why Habakkuk 2:4 is so important for Paul: the righteous will live when the day of wrath comes, first on Israel, then on the pagan enemy, by virtue of a faithfulness that will not shrink back in fear. Similarly, Abraham’s faith is prototypical because it is faith in the promise regarding the future of his descendants. However, once faith or faithfulness—rather than adherence to the Law—has been established as the means by which the eschatological community in Jesus will find its way through the upheavals and afflictions to the life of the age to come, there is nothing to prevent the inclusion of Gentiles. That sets up the argument with Judaism about the grounds for membership, but it is secondary to the core question of eschatological survival.

- 1See also S. Westerholm,Perspectives Old and New on Paul: The “Lutheran” Paul and His Critics (Eerdmans, 2003).

The meaning of the wrath of God is one thing which distinguishes the NP writers and Westerholm from yourself, but there's another distinction which is bothering me.

My understanding from Wright is that justification is not so much an answer to the question about qualification for entry to the people of God, but how they are identified once they are in.

Again, from Wright, my understanding is that the proclamation of Jesus generates faith in the hearer (or not, as the case may be); that faith is then the basis of justification after it has appeared.

If this understanding of Wright is correct, then justification by faith would not answer the question how does the individual gain entrance to the people of God, but how is the individual recognised, along with all God's people, once he/she is there.

The distinction has big implications. I'd be interested to know if anyone feels this is how Wright sees things. I do wonder if Westerholm is holding one view of justification (entrance to the people of God) in his survey of NP writers, while they are holding something rather different.

All this makes my head swim. I doubt it is even possible to fully understand what Paul meant. He was a person with a completely different world view writing to unknown people in the context of events that we cannot know.

To top it off, half of the references may not even have been written by Paul. For example, you quote II Timothy, but the pastorals were almost certainly written by others well after Paul's death. So the epistles reflect development of thought by multiple authors, which makes it difficult to try and reconcile all the biblical references to the term.

I do agree that the meaning of the term has to be seen in a corporate light, because IMO first-century Jews were not obssessed with personal salvation.

@paulf:

The trouble is that the “church” is stuck with the Bible as an account of its origins, so I think we have to do the hard work of trying to make sense of it. Much of the difficulty, as I suggested in the previous post, comes from having to find a way through the forest of tangled, contradictory, ill-conceived theologies that has grown up around the text. But progress is possible—witness our agreement that the Jews were not obsessed, in the manner of modern evangelicals, with personal salvation.

@Andrew Perriman:

True, but then again like Peter I am not convinced about the 70-AD part of the narrative. And I'm certainly no expert.

Part of me thinks that all complicated theology should be completely discounted because the writers of the texts were formulating a relatively new set of beliefs addressing a not-very-educated audience. Anything too nuanced would probably have not been understood or well-received. But even if I am right that doesn't help to understand the texts as much as discount some of the theology that developed many years later.

Recent comments