I made the comment in part 1 of this review of Steve Chalke’s The Lost Message of Paul that he has worked hard to integrate recent New Testament scholarship into his analysis of Paul but that in the end his personal judgment as a post-evangelical pastor gets the better of him. That started me thinking about a little schematisation of the different standpoints from which we interpret the New Testament and of the different hermeneutical journeys that we are on. Then I’ll get back to the details of his attempt to rescue the lost message of Paul.

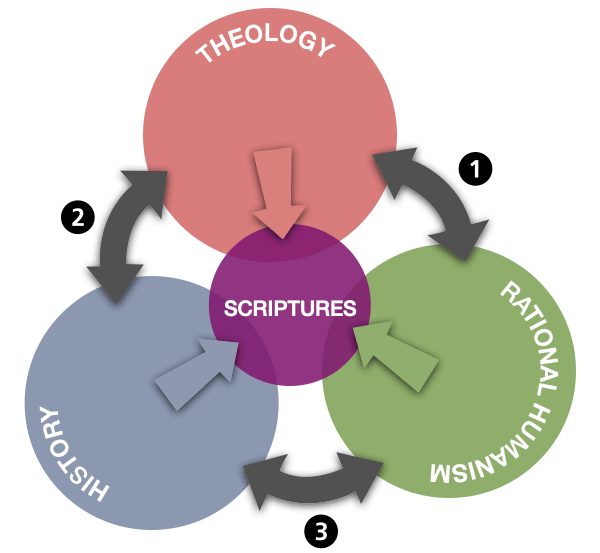

The three basic hermeneutical positions are theology, rational humanism and history.

By theology I mean that more or less formal body of beliefs and doctrines that has been handed down through the ages, along diverse ecclesiastical channels, as the expression and standard of Christian orthodoxy. It has two main theses: first, that God is and always has been three-in-one, Father, Son and Holy Spirit; secondly, that the triune God sent the eternal Son into the world to redeem sinful humanity. Theology tends to read the scriptures with a view to defending these theses and subsidiary propositions and is frequently open to the charge that it does so in a rather heavy-handed fashion.

In the West we are all, functionally, rational humanists, whatever we may call ourselves. There are very few areas where we consciously and consistently opt out of the modern worldview. We are mostly very comfortable here, no doubt much too comfortable. We also instinctively read the scriptures as rational humanists. We may affirm a belief in the miracles of Jesus, but I suspect that that is possible largely because we have assimilated the story as something more like “myth”—an enclosed “world of the text” isolated from history and real human experience. We also, I think it is fair to say, adhere to a moral system that prioritises personal well-being and social justice over the sovereignty of God. We read the Bible in search of ideas and language that will support that instinctual perspective, carefully avoiding, or creatively reinterpreting, those texts which seem stuck in a barbaric and unenlightened age.

The modern historical approach to the scriptures is the child of rational humanism, once unruly and destructive but now quite grown up and less likely to trash the place. The aim is to understand the texts as the product of the ancient communities which produced and first read them, on the assumption that their worldview and historical outlook are an integral part of the meaning of the texts. We rely on a critical methodology and some basic humility to correct for our cultural and intellectual biases as modern readers, but it’s not beyond us to decide, for example, that Jesus’ parable of the two houses and the coming storm applied not to the saved and the unsaved throughout the ages but to first century Israel, with the devastating war against Rome on the horizon.

These are the main hermeneutical positions—the places from which interpretation is done—and there are certainly those who refuse to budge from their settled positions. But perhaps the more interesting thought is generated as people move backwards and forwards along the pathways between the consolidated positions.

1. Liberal and progressive theologies mostly take shape in an exodus journey along the path between theological orthodoxy and rational humanism. Steve Chalke’s ethical-theological critique of penal substitution atonement is a good example.

2. Matthew Bates, I think, is a good example of someone treading the second path. He sets out with a high christology, but his argument about “salvation by allegiance alone” is an engagement with the concrete historical experience of the early community as it lived out its commitment to the risen Jesus. Roughly speaking, his reading of the New Testament is strongly supportive of the first theological proposition about the triune identity of God, but he is somewhat less enthusiastic about traditional definitions of salvation. The early church, on the other hand, as it settled in the Greek-Roman world, was marching resolutely away from history towards a theological reconstruction of the world.

3. I would put myself firmly in the history category, and a lot of work has to be done to defend it against the strident demands of theology and seductive lure of rational humanism. But my book on same-sex relationships is an attempt to understand how the historical narrative lands in the age after the age to come (if you see what I mean). So I have set out on a journey from a thoroughgoing historical reading of the New Testament, asking how we are to keep telling this story under the radically changed and still changing conditions of modernity—though a more comprehensive account might go the other way round the diagram, by way of theological tradition.

Steve Chalke is also on this path, but heading in the opposite direction, and he’s on a tether—intrigued by the new perspectives on Paul that have emerged over the last few decades, but reluctant to go all the way and inhabit the narrow and sometimes quite discomforting outlook of Jesus and the apostles. It remains a useful exercise, but my argument would be that until we fully grasp the contingencies of that original proclamation of the coming rule of God over the nations, we will struggle to maintain a distinctive witness to the creator God who is the God of history, as we approach a time, in all probability, of massive global upheaval.

You might want to consider where you are on this diagram, and which direction, if any, you’re travelling in.

Danke für die schöne Antwort auf meine quälende Frage. Historisch bleiben. Historisch bleiben. Historisch bleiben. Ja. Und wir müssen ein Narrativ erfinden (weiter spinnen), das möglichst gut diese „wirkliche Welt“ erklärt. Ist das aber nicht heute die Aufgabe der Naturwissenschaft? Wie hat hier Gott seinen Platz. Enden wir dann nicht im Pantheismus oder Panentheismus?

Das ist der Weg, den Walter Wink mit seiner Berühmten Trilogie über die „Mächte“ beschritt. Ich finden seinen Grundansatz immer noch nötig. Ergänzt um deine Brille könnte das 3-dimensionales Sehen werden…. Sagte ich das bereits?

–—

Thank you for the beautiful answer to my haunting question. Keep it historical. Stay historical. Stay historical. Stay historical. And we have to invent (continue to spin) a narrative that explains this “real world” as well as possible. But isn’t that the task of science today? How does God have his place here. Do we not end up in pantheism or panentheism?

This is the path Walter Wink took with his famous trilogy about the “Powers”. I still find his basic approach necessary. Complemented by your glasses, three-dimensional vision could become… Did I say that already?

Recent comments