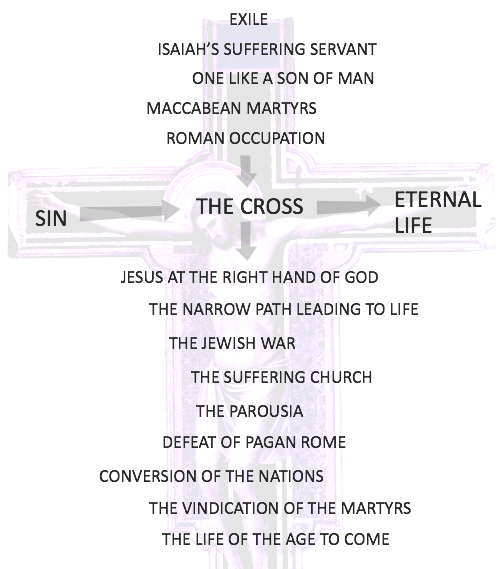

There is a simple, universal or cosmic or existential narrative of the cross—the horizontal beam. Humanity has fallen, every individual person has sinned and must go by way of the cross to gain eternal life. But, for all its merits, this is a theological abstraction. It is not the biblical narrative.

The biblical narrative of the cross is not universal or cosmic or existential and it is nothing like as simple. It is historical—the vertical piece, which sustains whatever else we may wish to say.

It arises out of the story of ancient Israel. The brutal execution of Jesus by the Romans is a critical moment in the story of how the descendants of Abraham made the long and arduous journey from exile to empire, from judgment to justification, from sin to forgiveness, from Law to Spirit, from death to the life of the age to come.

The cross pre-empted both the dreadful punishment that would be inflicted on the Jewish people by Rome and the suffering of those followers of the narrow way, who believed that YHWH had made Jesus both Lord and Christ. The cross makes no sense apart from these historical outcomes.

It was real, it had substitutionary atoning value for Israel, and it demolished the wall of the Law by which Gentiles were debarred from the covenant people, with all its amazing privileges and heavy responsibilities. Without it, we would not now be reconciled to the creator God, we would not be his people, there would be no people to be part of, we would not have the Spirit of God, we would have no hope of new life.

On Good Friday, of course, both stories of the cross need to be told.

On the subject of horizontal and vertical beams, Max Turner (New Bible Commentary) has this to say, starting with the wall, which debarred Gentiles from the covenant people and was demolished by the cross:

He (Paul in Ephesians 2:14-18) begins with the horizontal dimension. Jesus is said to be our peace in the sense that he joined the two great divisions of humanity (circumcision and uncircumcision) into one … God wished to create one new humanity out of Jew and Gentile.

Turner continues:

16 now turns to the vertical dimension … His point is that Jesus at the cross stood as representative not only of the Jew but of Gentile humanity too, as the last Adam (Rom. 5:12-21; 1 Cor. 15:45; Phil. 2:5-11). In the first instance it was uniquely in himself (15) that he made the one man out of the two; and subsequently it is only by union with him in one body that cosmic reconciliation is experienced. This means the church really is, for Paul, a third entity — neither Jew nor Gentile, but new humanity.

Was Paul (or whoever wrote Ephesians) introducing a ‘universal, cosmic or existential’ interpretation of the narrative, or was that part of the narrative all along? Could Jesus have been a representative of Gentiles as well as Jews at the cross after all?

@peter wilkinson:

Andrew & Peter,

In Turner’s quote he states:

In the first instance it was uniquely in himself (15) that he made the one man out of the two.

What two men are God making the one new man from?

This expression comes from Paul in Eph. 2:15 where he states

15 by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace

But, up in verse 11-12 he states

11 Therefore remember that at one time you Gentiles in the flesh, called “the uncircumcision” by what is called the circumcision, which is made in the flesh by hands— 12 remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world.

Here Paul states the Gentile (man) — which is clearly one of the two men- prior to Christ, were not just alienated from the commonwealth of Israel, but “strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world.”

Were not the “covenants of promise”, “hope” and the establishment of a relationship with God (contrasting the phrase without God in the world) things established back in Genesis?

Hosea 6:7 clearly takes the covenant back to Adam, yet Paul states that Gentiles were strangers to all covenants.

Paul also in 1 Cor. 15 ties the law to Adam, which he also refers to as the first man, yet the law applied only to Israel.

Seems to me that Paul’s two men are 1) the Gentile man and 2) the Israel/Jewish/circumcised man which he ties back to (the first) Adam. Thus we have the identity of Paul’s other man.

Even the link Andrew posted in this article (Atonement, without the theoretical nonsense) stresses the distinction between the two men (Jew and Gentile).

In that article Andrew you highlight that Jesus atoned for Israel’s sin. Is that not because it was Israel that was under sin and death (which started with Adam) due to law? Again, this links the first Adam only to Israel.

Am I the only one who sees this and the implications of this? To me it’s like a gigantic elephant standing in the room.

@Rich:

Were not the “covenants of promise”, “hope” and the establishment of a relationship with God (contrasting the phrase without God in the world) things established back in Genesis?

The covenants of promise are the covenants with Israel and go back to Abraham—the promise of inheritance. No?

Hosea 6:7 clearly takes the covenant back to Adam, yet Paul states that Gentiles were strangers to all covenants.

The issue here in the first place is the translation. Stuart, for example, has:

But look—they have walked on my covenant like it was dirt, see, they have betrayed me!

The LXX has taken כְּאָדָ֖ם to mean “as a man”:

But they are like a person (ὡς ἄνθρωπος) transgressing a covenant; there he despised me.

But even if the reference is to Adam, the point would only be that Israel transgressed the covenant with Moses in the same was as Adam transgressed the original commandment. I think this is pretty much Paul’s argument in Romans about Israel—that the Jews are no different to the rest of humanity in Adam, no less enslaved to sin. Adam’s transgression is a precursor to or type of Israel’s transgression, but this does not link Adam “only” to Israel, as you suggest. Israel sins because it is in Adam—but only in the sense that it shares a common humanity with all other peoples.

Recent comments