In a comment on an old post looking at a review by Larry Hurtado of Dunn’s Did the First Christians Worship Jesus, Marc Taylor maintains that “Dunn’s assertion that certain prayer words are not used in reference to the Lord Jesus is without merit.” He lists four passages in Acts and a handful from Paul and James in support of his claim. The debate is an interesting one. Here I want briefly to review the Acts texts and propose a different model to account for the data.

A general pattern of prayer to God

In Luke’s Gospel Jesus teaches his disciples to pray to their Father in heaven. For example, they are taught to pray, “Father, hallowed be your name… lead us not into testing” (Lk. 11:2-4). They are to pray steadfastly, confident that “God will give justice to his elect” (Lk. 18:1-7). On the Mount of Olives Jesus prays to his Father and then urges his disciples to rise and “pray that you may not enter into testing” (Lk. 22:39-40). Notice the consistent eschatological orientation of this prayer. After the resurrection Jesus does not promise to answer their prayers to him; rather, they will receive the Spirit from God (Lk. 24:49).

Most of the references to prayer in Acts are of a general kind: the disciples “were devoting themselves to prayer” (Acts 1:14; cf. 2:42; 6:4). Peter and John pray that the disciples in Samaria will receive the Holy Spirit (Acts 8:14-15; Peter prays for Tabitha (Acts 9:40); Paul prays with the Ephesian elders and for a man sick with dysentery (Acts 20:36; 28:8). The assumption is probably that such prayer is directed to God—so, for example: “About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God…” (Acts 16:25).

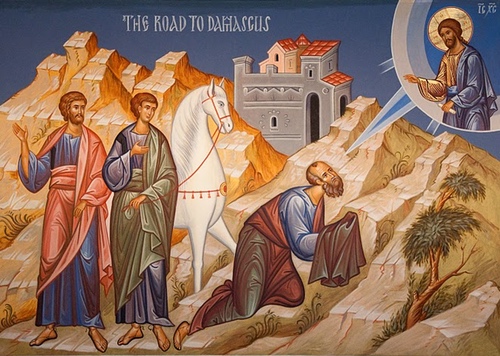

Visions of the risen Lord

We certainly see in Acts the disciples and Paul interacting verbally with the risen Lord Jesus in visions. At his martyrdom Stephen sees the heavens opened and he cries out to the “Son of Man, standing at the right hand of God”. He asks the “Lord Jesus” to receive his spirit and not to hold this sin against his persecutors (Acts 7:56-60). Both Paul and Ananias engage in conversation with the risen Lord Jesus in the story of Paul’s conversion in Acts 9:4-19 (cf. 22:6-10; 26:14-18). Similarly, when he is praying in the temple, Paul falls into a trance, and Jesus speaks to him about the need to get out of Jerusalem (Acts 22:17-21).

These experiences appear to constitute an alternative channel by which the risen Lord, seated at the right hand of God, related to his disciples and apostles with particular reference to their mission and suffering. It is quite different in its conception from the relationship of the disciples to God the Father through prayer.

Prayer to Jesus?

Marc highlights four passages, however, that may fall outside this pattern.

And they prayed (proseuxamenoi) and said, “You, Lord, who know the hearts of all, show which one of these two you have chosen (exelexō)… (Acts 1:24)

It is possible that this “Lord” is the Lord Jesus who first chose disciples for himself, but in Acts 2:39 it is the “Lord our God” who calls people to himself, and Peter says that he had been chosen (exelexato) by God to proclaim the gospel to the Gentiles: “Brothers, you know that in the early days God made a choice (exelexato) among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe” (Acts 15:7). 1 Samuel 16:7 and Romans 8:27 perhaps suggest further that it is God who knows the hearts of all. But taken in isolation, I’m not sure that the ambiguity of this passage can be resolved.

While they were worshipping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” Then after fasting and praying they laid their hands on them and sent them off. (Acts 13:2–3)

Here the reference to prayer, along with fasting, would appear to fit the “general” category of prayer to God (cf. Lk. 2:37; 5:33-35). But does the preceding reference to the disciples “worshipping the Lord” suggest that in fact prayer to Jesus is understood here?

The word for “worshipping” is leitourgountōn, which means “serving”, typically in a religious context—it is used frequently in the Septuagint for the service that the priests perform in the temple (cf. Heb. 10:11). This is a different idea to that signified by the more common word for worship proskuneō, which has connotations of prostration.

Didache 15:1 makes reference to the leitourgian of prophets and teachers, which alerts us to the fact that Luke highlights the fact that there were “prophets and teachers” at the church in Antioch (Acts 13:1).

The “service to the Lord” in this passage, therefore, most likely refers to the activity of the prophets and teachers, which led to the Spirit’s instruction to set apart Barnabas and Saul. This may well have been a “service” to the Lord Jesus, but the fasting and prayer of the whole community—not just of the prophets and teachers—remains categorically different. Bauckham misses this point when he argues that leitourgountōn is “suggestive of the centrality of Jesus as object of religious devotion” and here refers to “prayer in the broadest sense with Jesus as its focus”.1

A similar distinction probably holds in the third passage that Marc cites:

And when they had appointed elders for them in every church, with prayer and fasting they committed them to the Lord in whom they had believed. (Acts 14:23)

Paul and Barnabas appoint elders (perhaps by inspiration of the Holy Spirit) and commit them to the “Lord in whom they had believed” (presumably the Lord Jesus). But the prayer with fasting would accord with the general pattern. There is a restricted set of “services” which the church performs on behalf of, or for the sake of, the risen Lord. But this is against a backdrop of singing songs and praying, with fasting, to God.

“When I had returned to Jerusalem and was praying in the temple, I fell into a trance and saw him saying to me, ‘Make haste and get out of Jerusalem quickly, because they will not accept your testimony about me.’” (Acts 22:17–18)

This final passage, to my mind, fits the emerging pattern very well. Paul is praying (to God) in the temple—as Peter would have been praying to God on the roof (Acts 10:9). He then falls into a trance in which Jesus speaks to him. The text does not suggest that he is praying to the Lord Jesus, who appears to him in response.

To sum up

So I think we have a more complex situation than is suggested by the argument that Dunn is mistaken in claiming that prayer is not addressed to Jesus in Acts:

1. In general terms the worship and prayer of these communities was directed towards God.

2. The disciples and apostles on exceptional occasions interacted verbally with the risen Lord through visions.

3. A specific set of “services”, notably prophecy and teaching, were done for the risen Lord Jesus, having to do specifically with the administration of the mission which he had entrusted to his disciples.

4. This pattern preserves the distinction between God and the Lord Jesus who has been raised from death and seated at his right hand. Both the visionary encounters with the risen Lord and the prophetic “service” to the Lord presuppose the eschatological narrative about kingdom and vindication, which is the point I made in the original post.

5. It came up in the comments below with reference to Acts 22:17-18 that in verse 16 Paul is instructed by Ananias to be baptized, “calling on his name”. To call on the name of the Lord has to do with salvation (cf. Acts 2:21); it is to identify with, or seek help from, the one who will deliver his people from the wrath to come. In that respect it cannot be taken as paradigmatic for prayer generally. It explains Paul’s baptism, not his praying in the temple.

- 1R. Bauckham, Jesus and the God of Israel (2008), 129.

Thank you for this interesting article.

Acts 1:24-25 The evidence that the Lord Jesus is this recipient of this prayer is very convincing.

Alvah Hovey: The heart-knower is used of God in 15:8 shows only that it does not apply exclusively to Christ. The call of Peter in 15:7, which is ascribed to God, was a call, not to the apostleship, but to preach the gospel to the heathen…To deny that Peter would ascribe omniscience to Christ because in Jer. 17:10 it is said to be the prerogative of God to know the heart contradicts John 21:17 (A Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, page 39).

Alan Thompson: Some have suggested that because the language of knowing hearts is used in Acts 15:8 to refer to the Father, this must be prayer to the Father too. However, the prayer here to ‘the Lord’ to show them which apostle he ‘has chosen’ is also identical to language used at the beginning of the chapter, where Luke tells us about the instruction Jesus gave to his apostles whom ‘he had chosen’. This opening and closing ‘frame’ in Acts 1 regarding ‘the day he was taken up’, together with the immediately preceding references to ‘the Lord’ in this context (1:21), all indicate that ‘the Lord’ who is being prayed to in 1:24 is the Lord Jesus (The Acts of the Risen Jesus: Luke’s Account of God’s Unfolding Plan, D.A. Carson Editor, page 50).

See also (I am “rhino”):

http://forum.bible-discussion.com/showthread.php?32940-The-…

Concerning Acts 13:2 a good parallel passage is Acts 14:23. It reads: When they had appointed elders for them in every church, having prayed with fasting, they commended them to the Lord in whom they had believed. (NASB)

The Greek word for “appointed” is χειροτονέω and the only other time it is used is in 2 Corinthians 8:19 where it refers to the Lord Jesus (cf. 8:21).

Furthermore, when Luke writes concerning believing in the Lord it too refers to the Lord Jesus (Acts 11:17; 16:31; 22:19).

Concerning Acts 22:17 the context of this passage surrounds itself with communication with the Lord Jesus. In verse 16 the Lord Jesus is to be called upon which is in reference to praying to Him while verses 18 through 21 describe the conversation between Paul and the Lord Jesus.

16 Now why do you delay? Get up and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on His name.’

17 “It happened when I returned to Jerusalem and was praying in the temple, that I fell into a trance,

18 and I saw Him saying to me, ‘Make haste, and get out of Jerusalem quickly, because they will not accept your testimony about Me.’

19 And I said, ‘Lord, they themselves understand that in one synagogue after another I used to imprison and beat those who believed in You.

20 And when the blood of Your witness Stephen was being shed, I also was standing by approving, and watching out for the coats of those who were slaying him.’

21 And He said to me, ‘Go! For I will send you far away to the Gentiles.’” (NASB)

@Marc Taylor:

A couple of things first, in light of Jaco’s intervention. One, I’m replying to this for my own benefit primarily. I appreciate the fact that people often have entrenched positions—I have my own—and find it difficult to see other points of view, myself included. So I want at least to take Marc’s response seriously. Two, I’m not arguing against a trinitarian theology in general terms. My argument has always been that in defending our theologically determined perspectives, on either side of the christological debate, we mostly miss what is actually going on in these texts. So, for example, Marc, I notice that you have disregarded my points 2 and 3 in the conclusion above.

Oh, and finally, no bickering please.

- On the face of it, the argument that the prayer to the Lord who has “chosen” a replacement for Judas (Acts 1:24-25) is explained by Acts 1:2 is a strong one: “until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commands through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen” (Acts 1:2). There is something to be said for the view that the appointment of Matthias is meant to complete the direct appointment by Jesus of the twelve.

- But this is also the limitation of the argument. We have not yet had the giving of the Spirit at Pentecost. If this is indeed a prayer to the Lord Jesus, it arguably reflects the recency of Jesus’ concrete presence among them. It is more difficult to defend the practice of prayer to Jesus in Acts after Pentecost.

- The risen Jesus says to Ananias that Saul is a “choice vessel for me” (Acts 9:15). The language is different (skeuos eklogēs), and in Galatians 1:15 Paul says that it was God who set him apart and called him “to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles”. The implication here would be that God chose Paul for the sake of, or for the purposes of, his Son. So here we do have a call to apostleship ascribed to God, which might be taken as explanatory for Acts 1:24-25. If even Paul was not chosen by the risen Jesus but by God for the risen Jesus, we appear to have a strong case for thinking that the prayer of Acts 1:24-25 was addressed to the God who chooses apostles for the sake of his Son.

- Hovey’s argument about the “heart-knower” puts the cart before the horse. The issue is not whether kardiognōsta is restricted to Christ but whether there are exegetical grounds for thinking that a term that would naturally be applied to God (as in Acts 15:8, which I’d overlooked) has here been extended to Christ. It’s not out of the question, but it needs to be demonstrated, not just assumed. The fact that Peter says to Jesus in John 21:17 “you know everything” does not address the particular linguistic question.

- The comments on the three other passages look to me like very loose reading of the texts to support a predetermined position. To commit someone to the Lord is not to pray to the Lord, though I agree that the reference here is probably to Jesus (Acts 14:23). The prayer with fasting is something that they did before committing the disciples to the Lord. There is no reason to conclude that the prayer is directed towards anyone but God. The comparison with 2 Corinthians 8:19 adds nothing to the argument. “Calling on his name” (Acts 22:16), particularly in relation to baptism, does not mean, as far as I can see, “praying to him”; and I have pointed out already that direct communication with the risen Lord appears to be confined to visions. Prayer, as such, with the possible exception of Acts 1:24-25, is reserved for God.

@Andrew Perriman:

1. Concerning your previous points #2 and #3 I don’t see how that detracts at all from praying to the Lord Jesus. Please explain.

2. Your second point (prayer is to Jesus) in your most recent post seems to contradict your third point (prayer is not to Jesus in Acts 1:24). Unless I am misunderstanding you it seems you agree that Acts 1:24 is a prayer to the Lord Jesus thus contrary to Dunn you do agree that proseuchomai is being rendered unto Him. Is this correct?

3. The Geek word used for “apostelship” in Acts 1:25 is used in three other passages. They are Romans 1:5; 1 Corinthians 9:2 and Galatians 2:8. The first two passages clearly refer to the Lord Jesus while Galatians 2:8 is not clear cut as to whom it applies to. It should also be noted that concerning the word “ministry” that appears in Acts 1:25 Luke records Paul later on in which he specifically associates it with the Lord Jesus (Acts 20:24).

4. Concerning the fact that Christ fully knows the hearts of all is demonstrated in Revelation 2:23.

5. Concerning Acts 14:23 you assume the prayer must be to God when the proof for that assertion does not exist. Remember, it was Dunn who originally made the assertion that the Lord Jesus doesn’t receive certain prayer words.

6. To call upon the name of the Lord is always used in the Old Testament in reference to prayer to the Lord (Psalm 86:5-7; Psalm 116:4; Lamentations 3:55-57).

NIDNOTTE: The very first prayer is mentioned in Gen 4:26: “At that time men began to call on the name of the LORD”. Before that time “men” (Adam, Eve, Cain) conversed directly with the Lord (3:8-19; 4:6-7, 9, 10-15). Now, bridging the developing gap, people began to communicate with God through prayer (4:1062, Prayer, P.A. Verhoef).

Newman and Nida: (Acts 9:14) The phrase call on your name is equivalent to “worship you.”

It must not be understood merely in the sense “speaking a person’s name.” It can, however, be understood as “using your name as they pray” (A Translator’s Handbook on The Acts of the Apostles, Barclay Newman and Eugene Nida, page 191).

Many more can be cited that affirm the same thing.

Thank you

@Marc Taylor:

Marc, thanks for the careful response.

1. My point is not so much that it detracts but that these two types of interaction (vision and prophetic service) are much more significant in Acts than the debatable idea that the disciples prayed to Jesus.

2. I’ve gone backwards and forwards on the interpretation of Acts 1:24-25. At the moment, it seems most likely to me that prayer to the Lord Jesus here brings closure to the choosing of the twelve. But I’m not persuaded that this is then normative for the rest of Acts. It looks to me like an exceptional usage which brings to a conclusion the story of Jesus’ earthly calling of the twelve.

I have to say, too, that I don’t have an objection in principle to the idea that the disciples prayed to Jesus as God’s eschatological agent. It just seems to me, on the whole, that Luke preserves a distinction (perhaps with the exception of 1:24-25) between prayer to God and these other modes of communicating with the risen Lord Jesus.

3. Paul does not say in either Romans 1:5 or 2 Corinthians 9:2 that he received apostleship from Jesus or because he had been chosen by Jesus. In Romans 1:5 he says that he received apostleship “through” Jesus; and in 2 Corinthians 9:2 it is not his apostleship but the “seal of his apostleship” (i.e. the Corinthians) that is in the Lord. Galatians 2:8 is not about election.

4. This is a fair observation, but it still doesn’t address the point. i) In Revelation 2:23 the thought is of examining (eraunōn) the heart—it has to do with judgment, which is not the case in Acts 1:24. ii) The word kardiognōsta occurs only in these two places in Acts. In 15:8 it is applied unambiguously to God. I think the burden of proof lies with those who think it is applied to Jesus in the ambiguous setting of 1:24-25. This is one of the reasons why I have been in two minds.

5. There is no need to prove that prayer is to God. That is the fundamental Jewish starting point, and it is upheld by the evidence of Luke’s Gospel. Elsewhere in Luke-Acts prayer and fasting follows convention. Anna worship God “with fasting and prayer” (Lk. 2:37). Jesus expects his disciples to fast and pray (implicitly to God) after his death (Lk. 5:33-34). Nehemiah “continued fasting and praying before the God of heaven” (Neh. 1:4). Daniel turns his face to the Lord God, “seeking him by prayer… with fasting” (Dan. 9:3). In view of this, it seems pretty reasonable to me to assume that in Acts 13:3 and 14:23 the disciples fast and pray to God. In Acts 12:4 we are told explicitly that “earnest prayer for him was made to God by the church”. There is no equivalent statement regarding Jesus.

6. I would suggest that in the context of Acts calling on the name of the Lord looks back to the quotation from Joel in Acts 2:21: “And it shall come to pass that everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord shall be saved.” The Jewish believers in Damascus who called on the name of the Lord (Acts 9:14; 9:21) had done so in order to save themselves from the current crooked generation of Israel. Ananias (note we are still in Damascus) instructs Paul to be baptised to wash away the sins of the corrupt generation in Jerusalem and to call on the name of the Lord in order to be saved from the coming wrath against Israel.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hello Andrew, Thank you for your response.

1. Thanks for clarifying your point concerning Acts 1:24-25.

2. Let me rephrase my comments concerning “apostleship”. Every time (Galatians 2:8 isn’t specific though) this particular Greek word for apostleship (apostolē) is used in association with the “Lord” it is always in reference to the Lord Jesus (Romans 1:5 and 1 Corinthians 9:2). There is not one clear cut case it is not used in association with Him.

3. Since the Lord Jesus fully knows the hearts of all concerning judgment then how is it in anyway limited when it comes to choosing a new apostle? Returning to John 21:17: Kurie panta su oidas ––> Lord, Thou knowest all things (John 21:17). Su Kurie kardiognōsta pantōn –—> Thou, Lord, which knowest the hearts of all (Acts 1:24) After stating that the Lord knew his heart Peter would later affirm that the same Lord knew every heart. George Beasley-Murray (On John 21:17): By this time all the old self-confidence and assertiveness manifest in Peter before the crucifixion of Jesus had drained away. He could only appeal to the Lord’s totality of knowledge, which included his knowledge of Peter’s heart (Word Biblical Commentary, John, Volume 36, page 405). Furthermore, 1 Peter 2:25 teaches the same thing in reference to the Lord Jesus. Although the exact term is not used in this passage there is more than one way to express the same truth claim.

4. To call upon the name of the Lord is used 3 more times in reference to the Lord Jesus by Paul (Romans 10:13; 1 Corinthians 1:2 and 2 Timothy 2:22) and all of them refer to praying to the Lord Jesus. Praying to the Lord is how the expression ‘to call upon the Lord’ was understood in the Old Testament, in the book of Acts and then later on in Paul’s writings. It should also be noted that it is not specifically clear as to whom the “Lord” applies to in Acts 2:21.

@Marc Taylor:

2. Obviously apostleship has reference to Jesus—that is not the issue. My observation was that when Paul speaks about his apostleship in Galatians, he appears to differentiate between the calling and the purpose: he is chosen by God for the sake of the Son. This may—I only say “may”—be grounds for thinking that in Acts 1:24-25 prayer is to the Lord God who has chosen…. But I’m not pressing the point.

3. As I said, you are still avoiding the linguistic problem. The word kardiognōstēs is found only here and in Acts 15:8 in the New Testament and is not used outside Christian literature. In Acts 15:8 it unequivocally refers to God in a similar context: “God made a choice (exelexato) among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe” (Acts 15:7). To my mind, exegetically, this weighs against the argument that the prayer of Acts 1:24-25 is directed to the Lord Jesus—though on balance it still seems more likely that this is an exceptional instance.

4. I repeat my point that calling on the name of the Lord—whether with reference to God or to Jesus—has to do specifically with being saved from the coming wrath. Christians are, in effect, identified as those who call on the name of the Lord in the current eschatological crisis—it sets them apart both from the Jews and from the Greeks. The Thessalonian believers were waiting for God’s Son from heaven, who would deliver them from the wrath to come. Calling on the name of the Lord is an important verbal interaction with the risen Lord Jesus (I’ve added it to my summary in the original post) but it cannot be taken as a general form of prayer.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hello Andrew,

1. Since kyrios predominately refers to Jesus and theos to the Father kardiognōstēs in Acts 1:24 is applied to the Lord Jesus and in Acts 15:8 it is applied to the Father. ‘Lord’ is used in Acts 1:24 but it is not used in Acts 15:8 — here ‘God’ is employed.

Alan Thompson: One other distant use of the term is not enough evidence to outweigh the nearer context of Acts 1:2 (One Lord, One People: The Unity of the Church in Acts in Its Literary Setting, Page 67 Footnote #67).

Nigel Turner: At a meeting before the day of Pentecost Christ is addressed as, ‘Thou, Lord, which knowest the hearts of all men’ (Acts 1:24), and Peter at the council of Jerusalem testifies concerning ‘God, which knoweth the hearts’ (15:8) (Christian Words, kardiognwstes, page 202).

2. There is not one time in the Bible where to call upon the name of the Lord does not refer to prayer. I already cited Genesis 4:26 which shows from the beginning how this expression is to be understood.

As the TDNT points out, “calling on the Lord from a pure heart (2 Timothy 2:22) is the same as worship with a clear conscience (2 Timothy 1:3)” (7:918, conscience, Maurer).

The Greek word used in 2 Timothy 1:3 is latreuō and if one is offering this form of worship prayer can in no way be diminished.

@Marc Taylor:

Many of the occurrences of kyrios are disputed, and there are enough that clearly refer to God to leave doubt about 1:24-25, particularly given the application of kardiognōstēs to God in 15:8. As I said, I’m inclined to agree with you about this one, but I don’t think it’s exegetically cut-and-dried.

I would still maintain that in the context of Acts when Paul is baptised “calling on his name”, the reference is to the specific idiom of Acts 2:21. I am not convinced that “calling on someone’s name” simply means “praying to someone” in general terms. T. Levi 5:5 is interesting: ‘And I said to him: “I beg you, lord, tell me your name, that I may call on you in a day of tribulation.”’ This is spoken to an angel. Levi wants to know how he can get in touch with him in a time of trouble. It’s prayer, but not any old prayer.

But even if you want to insist on a broader usage, there is no reason to read “praying in the temple” as an expression or instance of “calling on his name”. Paul did not get baptised in the temple. He got baptised, calling on the name of Jesus. Then later, after he had returned to Jerusalem, he went to the temple and prayed to God. The narrative gives us no reason to think that his prayer in the temple was addressed to Jesus or was intended as an example of calling on the name of the Lord. Here I definitely don’t agree with you.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hello Andrew,

When one reads Acts 1:24-25 every key word that is used all point to the Lord Jesus. Since you are more strongly in favor that this prayer refers to the Lord Jesus I think it is best we leave it at that. Even though you view it as an exception you are not behind Dunn in his assertion that proseuchomai is never used in reference to the Lord Jesus.

In fact, at one time Dunn wasn’t as absolute that it didn’t refer to the Lord Jesus as well. In ‘Beginning from Jerusalem’ he wrote that the “prayer in 1.24 probably addresses God”( page 220 footnote #249, the bold face is mine).

In terms of calling on the name of the Lord I asserted that it is always understood as prayer in the Bible. Other sources may use it differently but that is not the case with what God intended for its use in Scripture.

I agree that it does not specifically teach that prayer was to the Lord Jesus in Acts 22:17 but the entire event is surrounded by communication/prayer with the Lord Jesus. See point #5 in my comment as well.

http://www.postost.net/comment/5844#comment-5844

My point is that for those who strictly maintain that the Lord Jesus is never the proper recipient of proseuchomai the evidence is simply not as clear cut for them to insist on such an affirmation.

@Andrew Perriman:

I am not convinced that “calling on someone’s name” simply means “praying to someone” in general terms.

Andrew… so in this sense, would it be fair to view this “calling on someone’s name” in terms of simply ‘invoking’ the name; thus making a public declaration of allegiance to, in this case Jesus, as opposed to the likes of Caesar? Or is that going too far?

@davo:

It’s not where we start in Acts 2, but I think it likely that the phrase acquired connotations of that sort, yes. We miss its “political” and eschatological force if we reduce it to a model of prayer to Jesus.

@Andrew Perriman:

Why can’t it encompass all of them?

@Marc Taylor:

It’s a bit like saying green is a colour but not all colours are green. Green is used for certain purposes—it is used for “go” on traffic lights, or by artists for painting leaves. If green was also used for “stop” or for painting goldfish, it would get very confusing.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thanks Andrew.

Besides the evidence I cited many Bible dictionaries and other authorities affirm that to call upon the name of the Lord refers to prayer/worship.

Andrew,

These and many more points have been highlighted in the past to Marc Taylor on two blogs I have also participated in. To demonstrate the endless goal-shifting and repetitio ad naseam you’re setting yourself up for, do some background checks here: http://trinities.org/blog/does-mark-teach-that-jesus-is-god/ and here: http://trinities.org/blog/hurtado-on-the-worship-of-jesus/ — in particular the comments. Taylor likes to troll pages critical of his views.

Good luck.

Recent comments