Here we go again.

In a response to my recent piece on James Tabor’s “failed failed apocalypse of the New Testament” argument, Edward Babinski, one of a number of vociferous ex-fundamentalist critics of conservative orthodoxies, has outlined an obscure but interesting argument regarding Jesus’ belief in an imminent cosmic judgment, based on the Book of the Watchers in 1 Enoch (1 En. 1-36). I offered a brief response, but on further reflection, I think that any analogy between the Book of the Watchers and the apocalyptic outlook of the New Testament points in quite a different direction. I will suggest that Jesus actually comes off the better for it.

The judgment of the rebellious angels

In the period before the flood, according to the Enoch text, some of the angels, led by Semyaz, descended from heaven and had sexual relations with women (1 En. 7:1-6; cf. Gen. 6:1-4). The women gave birth to giants who consumed so much—even devouring human flesh—that “the earth brought an accusation against the oppressors.” The rebellious angels instructed people in the production of weapons and armour, ornamentation, in astrology and magical arts, leading to bloodshed and oppression.

In response, God first sends warning to Noah to prepare to escape the deluge that is about to come upon the earth, then commands the angel Raphael to bind Azazʾel hand and foot, who had taught humanity warfare, and bury him in a hole in the desert “in order that he may be sent into the fire on the great day of judgment” (1 En. 10:1-6). There will be a great battle among the fallen angels and their offspring, after which the remaining angels will be bound “for seventy generations underneath the rocks of the ground until the day of their judgment and of their consummation, until the eternal judgment is concluded” (1 En. 10:12).

The basic apocalyptic idea, therefore, is that the technologies and sciences that have corrupted human societies, resulting in injustice and violence, were introduced into the world by fallen angelic powers. The problem is resolved at two levels: first, corrupted humanity is destroyed in a cataclysm; secondly, the angels are imprisoned in the earth until a final judgment so that they cannot lead the world astray.

In the later Similitudes of Enoch that judgment is presided over by the Elect One, who is the Son of Man, who will “remove the kings and the mighty ones from their comfortable seats and the strong ones from their thrones. He shall loosen the reins of the strong and crush the teeth of the sinners (1En. 46:4). As part of this political judgment against the unrighteous in Israel, and perhaps also against Israel’s enemies, the Elect One will judge Azazʾel and his company (1 En. 55:4).

Luke’s genealogy

The sceptical argument is that the seventy generations of the angels’ imprisonment corresponds to the seventy generations from Enoch to Jesus in Luke’s genealogy (Lk. 3:23-38). What Luke is trying to say, therefore, is that the final judgment of both the angels and humanity will happen in conjunction with the coming of Jesus—or rather with his imminent second coming with the clouds of heaven as the Son of Man. It didn’t happen, therefore, the New Testament is fundamentally and irretrievably flawed.

The eleven-times-seven patterning of Luke’s genealogy (Lk. 3:23-38) is no doubt significant. There is nothing in the text to suggest, however, that he meant to present Jesus as the end of Enoch’s seventy generations. In fact, there’s a very good reason for thinking that in Luke and in the New Testament generally the apocalyptic schema of the Book of the Watchers has been revised and put to rather different use.

For a start, Luke’s genealogy runs backwards to Adam as “Son of God,” not forwards to Jesus as the Son of Man who will punish the wicked and the rebellious angels. It has been inserted between the baptism and temptation narratives seemingly to reinforce the identification of Jesus as the “beloved Son” with whom God is well pleased and as the “Son of God” whose sense of vocation is tested by Satan in the wilderness. This is not the apocalyptic Son of Man who is associated in the traditions with judgment but the “servant… my chosen, in whom my soul delights,” upon whom God has put his Spirit—in effect, the Son who has been sent to do the work of a servant in calling the apostate leadership of Israel to repentance (Is. 42:1; Lk. 20:9-18).

Conceivably, Luke has drawn on an apocalyptic tradition in which seventy-seven generations constitutes a significant period of time that is fulfilled in the coming of Jesus, but it is a period that transcends the seventy years of the imprisonment of the angels. No interest is shown in the person of Enoch as the beginning of a period that would climax in a cosmic judgment.

Jesus and the binding of Satan

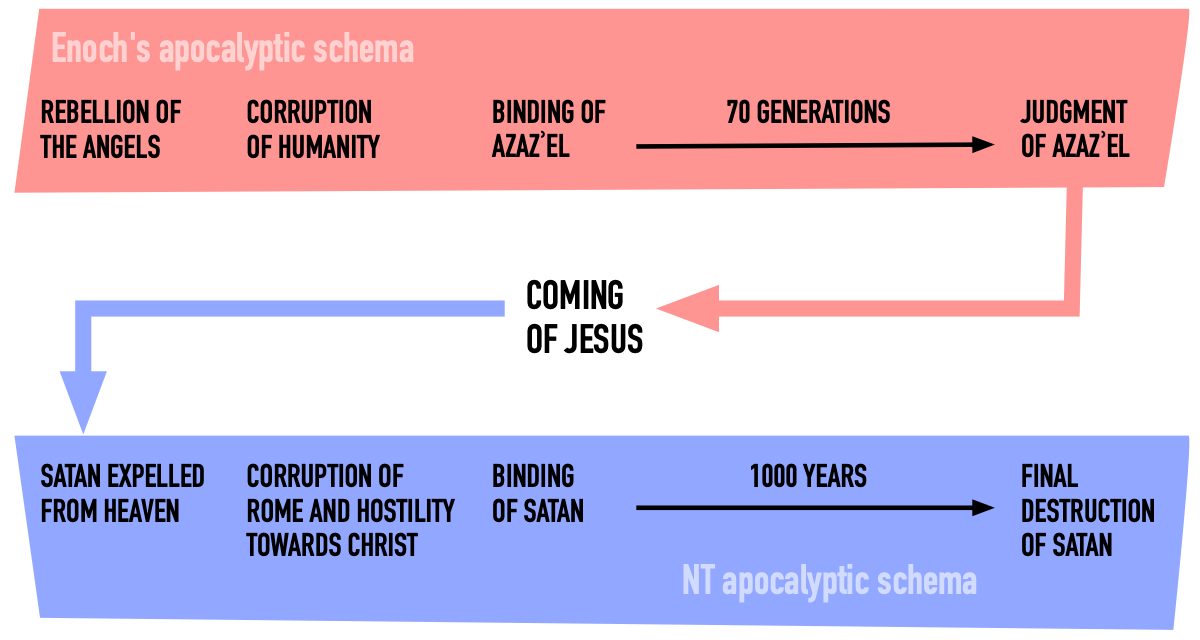

More to the point, what is evoked in the Gospels, and indeed in much of the rest of the New Testament, is not the conclusion to the cycle of the Enochic myth but its beginning. The whole storyline of rebellion → binding and burial → confinement → destruction has been shifted forwards to address an entirely different crisis.

It is apparent from the temptation story, which immediately follows the genealogy, that Satan is not currently bound and safely shut away in the earth but at liberty, active, and dangerous. It is only because Jesus turned down Satan’s offer of the kingdoms of the Greek-Roman world that he can plunder his house (Lk. 11:21-22; Matt. 12:29; Mk. 3:27). The man possessed by Legion is bound with chains and kept under guard, but still breaks loose and causes havoc (Lk. 8:29-30). Jesus liberates a woman who has been bound by Satan for 18 years (Lk. 13:6). He sees Satan fall like lightning from heaven, as a foreshadowing of the authority that his disciples will have in the future over the power of the enemy (Lk. 10:18). Satan enters into Judas, and he demands to sift Peter like wheat (Lk. 22:3, 31).

Paul knows that Satan is behind the opposition to the churches, the driving force behind the blasphemous Caesar-figure, the “man of lawlessness” (Rom. 16:20; 2 Cor. 2:11; 11:14; 2 Thess. 2:9-10). Satan disrupts the work of the apostles (2 Cor. 12:7; 1 Thess. 2:18).

In John’s mythology Satan is thrown down from heaven after the ascension of the child who will rule the nations, and he deceives the whole Greek-Roman oikoumenē into making war against “those who keep the commandments of God and hold to the testimony of Jesus” (Rev. 12:9, 17). Again, Satan is not buried in the earth awaiting judgment; he is the furious power behind the violent antipathy of Rome towards the Jews and the churches. He is a threat to the churches (Rev. 2:9, 13, 24; 3:9). The apocalyptic narrative reaches a climax in the overthrow of Babylon the great, which is Rome, and now at last an angel descends from heaven, binds Satan, and imprisons him in the abyss for a thousand years, after which he is destroyed in the lake of fire and sulphur (Rev. 20:1-3, 10).

So if the New Testament has adopted the punishment of the fallen angels motif from Jewish apocalypticism, it has shifted the timeframe by some distance.

In Enoch’s schema, the rebellious Watchers are active before the flood, they are imprisoned for seventy generations, and they will be destroyed finally in an Israel-centred judgment during the Greek-Roman period.

In the apocalyptic perspective of the New Testament, Satan is driven from heaven and becomes active on earth in connection with the birth of Jesus—the schema is not entirely consistent. His malign presence is revealed in the spiritual corruption and uncleanness of Israel, in his determination to subvert the mission of Jesus, in the blasphemous arrogance and might of Rome, and in the persecution and deception of the churches. He is restrained to a degree by the spiritual authority of Jesus and his followers, but he is not bound and buried under the earth by angelic agency until after the overthrow of Roman pagan imperial power. He is then imprisoned not for seventy generations but for a thousand years until a final judgment of all humanity, at which point he is destroyed.

So there’s no final judgment in Luke

The activity of Satan, in other words, is strictly confined to the period of Rome’s hostility towards Jesus and his followers. It will come to an end not with a final cosmic judgment but with the resolution of the historical crisis—the reform of God’s people and the triumph of the elect over the pagan oppressor. This is a political scenario, not a cosmic one; it happens in history, not at the end of history. The New Testament makes no attempt to describe an idyllic state or restored created order directly following on from the judgment of either Israel or Rome. Only at the end of the thousand years of Satan’s confinement does John see the appearance of a new heaven and earth, from which all wickedness, suffering, and death have been definitively abolished.

The other point to stress, finally, is that Luke makes use of the coming of the Son of Man motif for a very specific and limited purpose. Jesus has nothing to say about the transformation of the cosmos or even of Israel. There is judgment against Israel but not against the nations. The parable of the vineyard climaxes in the destruction of the wicked tenants and the transfer of the business to others. The war against Rome and the destruction of Jerusalem will cause great consternation, but if the disciples stay alert and faithful to their task, they will be vindicated before the Son of Man when he comes (Lk. 9:26; 21:28, 36), and he will give them justice against their enemies (Lk. 18:7-8).

That’s all there is to it.

I recently ran across your piece above. Am I merely an ex-fundamentalist critic of conservative orthodoxy? I daresay my biblical studies for ten years after having been a creationist in my youth took me beyond fundamentalism prior to leaving the fold entirely. I was already a moderate to liberal evangelical, even a univeralist, prior to leaving the fold.

And historical Jesus studies have presented quite clearly the evidence for Jesus as a final judgment prophet. It is a mainstream view in historical Jesus studies.

And so far as your attempts to harmonize Luke, Revelation, et al, into a tidy basket of fully consistent realized eschatology, good luck with that. The Bible is not that consistent. Even dispensationalists have argued with each other as to how many raptures there are, and also split into pre, mid, post-tribulationists. And preterists (which resembles your view more closely), are split quite “vociferously” into partial and full preterism. And the way they insert two thousand years between some verses in the synoptic Gospels’ “little apocalypse” chapters is a marvel to behold.

“Eschatology: Here to Stay,” a marvelously succinct presentation in Dale Allison’s, The Historical Christ and the Theological Jesus (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2009) https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10152632141161784…

New Testament Texts on the imminence of the End at Dr. James Tabor’s site:

https://pages.uncc.edu/james-tabor/christian-origins-and-th…

The Imminent End in the New Testament and Early Christian Literature (Ignatius, Shepherd of Hermas, Barnabas)

https://bible.markedward.red/p/the-imminent-end-in-new-test…

James D. G Dunn in Jesus Remembered, and in, The Evidence for Jesus, admits that Jesus believed in an imminent eschatological climax that did not happen. “Putting it bluntly, Jesus was proved wrong by the course of events.”

In Apocalypticism in the Bible and Its World: A Comprehensive Intro, Dr. Frederick J. Murphy concludes, “Christianity is the result of failed prophecy.” Urgent expectation of an imminent supernatural end pervades the NT http://www.bookreviews.org/bookdetail.asp?TitleId=8638

The Apocalyptic Worldview of Mark by Dr. David A. Sanchez [podcast from Loyola Marymount University]

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-apocalyptic-world…

Mark’s Jesus is a Thoroughly Apocalyptic Jesus

https://jesustweezers.home.blog/2020/02/01/marks-jesus-is-a…

For a discussion of how and why Old Testament prophecy developed into apocalyptic see Jesus the Apocalyptic Prophet

https://historyforatheists.com/2018/12/jesus-the-apocalypti…

Was Jesus a False Prophet? Probably

https://nonalchemist.wordpress.com/2020/04/22/was-jesus-a-f…

Scholarly Quotes on Paul the Apocalypticist

https://jesustweezers.home.blog/2020/03/19/scholarly-quotes…

Apostle Paul on the urgency engendered by the Lord’s soon coming in final judgment: https://edward-t-babinski.blogspot.com/2015/06/the-apostle-…

Paul the deluded apocalypticist

https://glentonjelbert.com/paul-the-deluded-apocalypticist/

A look at the wide array of “soon coming” passages in the NT and why the question of false prophecy is unavoidable, The Lowdown on God’s Showdown

https://infidels.org/kiosk/article/the-lowdown-on-gods-show…

Bart Ehrman’s apocalyptic Jesus view summarized

https://jamesbishopblog.com/2021/01/08/the-historical-jesus…

The eschatological final judgment was near according to early Christianity. So near that Jesus’ resurrection was the “first fruits.”

I’ll have a look at these, but I notice that a number of the links don’t work.

@Andrew Perriman:

You can still pull up defunct web pages by pasting the link into the Way Back Machine, also known as The Internet Archive.

Edward, thanks for coming back on this.

And historical Jesus studies have presented quite clearly the evidence for Jesus as a final judgment prophet. It is a mainstream view in historical Jesus studies.

Mainstream views have a habit of going out of fashion. I think scholars are right to stress the sense of the imminence of a catastrophic “end” in Jesus’ teaching, but wrong to conclude that he was talking about a final judgment and cosmic transformation. Jesus says nothing to that effect. His frame of reference is always Israel’s world. I think the historical case for saying that he had in view the “end” of Israel as a temple centred nation is very strong.

And so far as your attempts to harmonize Luke, Revelation, et al, into a tidy basket of fully consistent realized eschatology, good luck with that.

- I said in the article that the “schema is not entirely consistent.”

- The fractiousness of dispensationalists, preterists, etc., tells us nothing about the degree of historical coherence in the New Testament texts.

- My personal impression is that relocating the texts of the New Testament in the world of first century Judaism has gone a long way towards clarifying what holds the whole enterprise together. But, of course, that’s open to dispute.

@Andrew Perriman:

I tend to start investigations into NT predictions of a soon coming final cosmic judgment by citing the earliest NT writings, those of Paul, like in 1 Cor.

“‘The rulers of this age… are passing away’ [“will not last much longer” — Todayʼs English Version]… Do not go on passing judgment before the time [i.e., “before the time” of final judgment which he predicted was near at hand], but wait until the Lord comes who will both bring to light the things hidden in the darkness and disclose the motives of menʼs hearts… The time has been shortened so that from now on both those who have wives should be as though they had none… for the form of this world is passing away [“This world, as it is now, will not last much longer” — Todayʼs English Version]… …These things were written for our instruction, upon whom the ends of the ages have come.”

Equally explicit Pauline passages can be read here: https://edward-t-babinski.blogspot.com/2015/06/the-apostle-…

Th idea of a soon coming final cosmic judgment is explicitly seen in the book of Daniel, then a little later on it appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other inter-testamental literature. The book of Daniel was composed less than 100 years before the earliest known Dead Sea Scroll was composed, possibly 50 years before. The book of Daniel first came to people’s attention (or was “unsealed” as it says in the book) about 150 years before Jesus’ day. And it was only to be “unsealed” at “the time of the end,” when the time of final cosmic judgment was not far away, see Daniel 12:

“…There will be a time of distress such as has not happened from the beginning of nations until then. But at that time your people—everyone whose name is found written in the book—will be delivered. Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise will shine like the brightness of the heavens, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars for ever and ever. But you, Daniel, roll up and seal the words of the scroll until the time of the end… “How long will it be before these astonishing things are fulfilled?” „„and I heard him swear by him who lives forever, saying, “It will be for a time, times and half a time. When the power of the holy people has been finally broken, all these things will be completed.” I heard, but I did not understand. So I asked, “My lord, what will the outcome of all this be?… From the time that the daily sacrifice is abolished and the abomination that causes desolation is set up, there will be 1,290 days. Blessed is the one who waits for and reaches the end of the 1,335 days.”

One can easily see how such a prophecy excited people’s imaginations, especially a conquered people. The interesting thing is that the book of Daniel’s prediction of a final cosmic judgment (above) arose after Greeks had conquered and occupied Israel and desecrated the Temple. The book of Daniel was meant to inspire faith that the Greeks could be overcome, and a revolt against Greek rule did take place and was successful. But then the Romans arrived not long afterwards and conquered/occupied Israel, and desecrated the Temple, so Daniel was re-interpreted to now refer to the Romans, which is when the Dead Sea Scrolls were composed including their community rule book that described how to live in holy celibacy and await the final cosmic judgment. Many Dead Sea Scrolls featured quotations from the book of Daniel and some other prophets, all re-interpreted via Pesher to refer to their own generation.

http://home.earthlink.net/~ironmen/bgallery08.htm

Sons of Light vs. Sons of Darkness [from the Dead Sea Scrolls, War Scroll (1QM) 1.8-12]

‘8 (…righteousness) shall enlighten all the ends of the world. And the light will proceed until all the times of darkness are ended. And in the time of God, his great glory will shine for peace and blessing for all times. 9 (There shall be) glory and joy and length of days for all the sons of light. And on the day the Kittim fall, (there shall be) a battle and a fierce slaughter before the God 10 of Israel. For this is the day he appointed from of old, for a war to annihilate the sons of darkness. Then the congregation of gods and the assembly of man shall draw near for the great slaughter. 11 The sons of light and the lot of darkness shall do battle together for the Strength of God amid the sound of a great throng and the cries of gods and men. This is “the Day” [cf. Jer 30:7] 12 and it shall be a “time of distress” for the people God redeems. And there will be “nothing like it” in all their distress from the beginning to (it) end in everlasting redemption.’

The Dead Sea scrolls provide glimpses into the pre-Christian apocalytpic mindset. See the following email by Marcus Wood, BA, MA, Department of Theology, University of Durham: “In John Joseph Collins’ article ‘The Expectation of the End in the Dead Sea Scrolls’ in Evans/Flint (eds.) Eschatology, Messianism and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1997), much of Collins’ discussion centers on the pesharim [interpreters] and their belief in the ‘last days’ (esp. 1QpHab) and the claim that this could be calculated — roughly forty years [or a ‘generation’] after the death of the Teacher of Righteousness. [Such a belief was later paralleled in the Gospels: ‘This generation shall not pass away till all these things take place’ — Mark 13, Matthew 24, Luke 21].”

About 100 years after the earliest Dead Sea writings we see tensions between Rome and Israel continuing to rise and people like John the Baptist, Jesus and early Christian writers making yet more predictions of a coming final cosmic judgment — nearly every NT writing features such predictions. And the three synoptic Gospels feature lines from the book of Daniel. I have already shared a list of such passages collected at several websites, so let me share a few non-Christian passages as well, below:

NOTE ON 1OpHab

“1QpHab is a Qumran document found in 1947 and published by Burrows et al. in 1950. Its 13 columns of well-preserved Hebrew text contain a sectarian pesher [interpretive] commentary on Habakkuk 1 and 2… The handwriting style dates to 30-1 B.C.E.; the parchment was radiocarbon-dated to 120-5 B.C.E. (Vermes 1997, p. 478; Schiffman 1994, p. 226)… Since 1QpHab 9:7 refers to the Romans taking the wealth of the priests, the autograph probably dates to near 54 B.C.E., when the Romans plundered the Temple (Stegemann, p. 131)… Stegemann finds it significant that the Qumraners did not write any commentaries on the prophets in the last 100 years of their existence [from 70 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.] (p. 133). The Teacher of Righteousness had been dead a long time, and the end still had not come. Interest in prophecy may have waned.”

http://www.angelfire.com/md/mdmorrison/nt/1qphab.html

But we also see an interest in prophecy blossoming in groups other than those that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, as seen in these quotations from 1st century writings:

Lines from The Testament [also called Assumption] of Moses (1st century CE), 10 http://wesley.nnu.edu/index.php?id=2124

And then His kingdom shall appear throughout all His creation,

And then Satan shall be no more,…

Then the hands of the angel shall be filled

Who has been appointed chief,

And he shall forthwith avenge them of their [Israel’s] enemies.

For the Heavenly One will arise from His royal throne,

And He will go forth from His holy habitation

With indignation and wrath on account of His sons [of Israel].

And the earth shall tremble: to its confines shall it be shaken:…

And the horns of the sun shall be broken and he shall be turned into darkness;

And the moon shall not give her light, and be turned wholly into blood…

For the Most High will arise, the Eternal God alone,

And He will appear to punish the Gentiles,

And He will destroy all their idols.

Then you, O Israel, shall be happy,…

And God will exalt you,…

And you will look from on high and see your enemies in Ge(henna)…

And you shall give thanks and confess thy Creator.

And note the “eschatological or messianic woes” in 2 Esdras, composed near the end of the 1st century which reminds one of the woes in the little apocalypse in Mark 13, Matthew 24 and Luke 21:

“Now concerning the signs: behold, the days are coming when those who dwell on earth shall be seized with great terror, and the way of truth shall be hidden, and the land shall be barren of faith. And unrighteousness shall be increased beyond what you yourself see, and beyond what you heard of formerly. And the land which you now see ruling [i.e., Rome] shall be waste and untrodden, and men shall see it desolate [apparently via a supernatural act of God]. But if the Most High grants that you live, you shall see it thrown into confusion after the third period; and the sun shall suddenly shine forth at night, and the moon during the day. Blood shall drip from wood, and the stone shall utter its voice; the peoples shall be troubled, and the stars shall fall.” - 2 Esdras 5:1-54 (turn of the 1st century), an apocryphal book that appears in an appendix to the New Testament of the Vulgate [Catholic Bible], and among the apocrypha of several subsequent European versions of the Bible. http://www.biblestudytools.com/rsva/2-esdras/5.html

And note the expectation of “all things” being “brought to an end” in the Epistle of Barnabas, composed near the end of the 1st century and beginning of the next:

‘Of the Sabbath He speaketh in the beginning of the creation; And God made the works of His hands in six days, and He ended on the seventh day, and rested on it, and He hallowed it. Give heed, children, what this meaneth; He ended in six days. He meaneth this, that in six thousand years the Lord shall bring all things to an end; for the day with Him signifyeth a thousand years; and this He himself beareth me witness, saying; Behold, the day of the Lord shall be as a thousand years. Therefore, children, in six days, that is in six thousand years, everything shall come to an end. And He rested on the seventh day. this He meaneth; when His Son shall come, and shall abolish the time of the Lawless One [compare Romans 16:20, “…the God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet”], and shall judge the ungodly, and shall change the sun and the moon and the stars, then shall he truly rest on the seventh day.’ - http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-lightfoot.html 15:3-5 (late 1st century to early second century CE)

Justin Martyr in the middle of the 2nd century still preached an imminent final judgment:

“Since I bring from the Scriptures and the facts themselves both the proofs and the inculcation of them, do not delay or hesitate to put faith in me, although I am an uncircumcised man; so short a time is left you in which to become proselytes. If Christ’s coming shall have anticipated you, in vain you will repent, in vain you will weep; for He will not hear you.”

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/justinmartyr-dialoguetrypho.html” Dialogue with Typho 28:2

My date estimates are probably off, but I doubt the relative order of the documents I mentioned is greatly disputed.

This was what I meant when I was citing dates in my comment above.

“All eight manuscripts of the book of Daniel found among the Dead Sea Scrolls were copied between 125 BC (4QDanc) and about 50 AD (4QDanb), showing that Daniel was being read at Qumran only about 40 years after its composition.”

Book of Daniel - Wikipedia

Thanks, Edward. I’ve responded here.

Recent comments