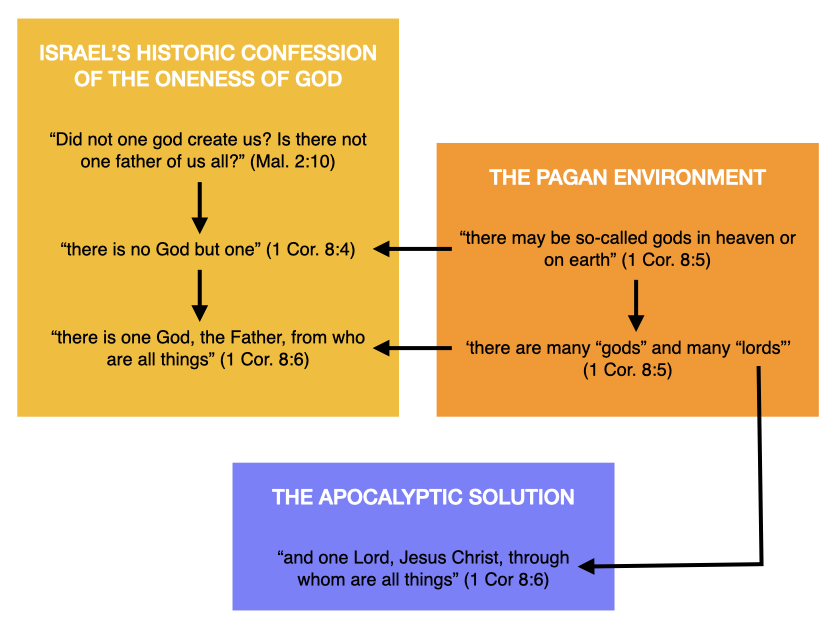

The passage critiques the popular view that Paul reworks the Shema (Deut. 6:4) in 1 Corinthians 8:6 to include Jesus in the divine identity by assigning him the title “Lord” (kyrios). Instead, it argues that Paul is not referencing the Shema at all, but contrasting the one true God of Israel with the many gods and lords of the pagan world. Jesus is not assimilated into God’s identity but is portrayed as God’s appointed ruler within an apocalyptic narrative. His lordship reflects authority given to judge and reign, not intrinsic divinity, with Trinitarian theology developing later from Greek philosophical frameworks.

Here is the question. When Paul says, “for us one God the Father…, and one Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 8:6), are the terms “God… Lord” between them a reference to the shemaʿ: “Hear, Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Deut. 8:6 LXX*)?

It has become a stock argument of those holding to an Early High Christology that Paul has assimilated Jesus into the divine identity by reassigning to him the designation kyrios in the shemaʿ. So, for example, Gordon Fee:

What Paul has done seems plain enough. He has kept the ‘one’ intact, but he has divided the Shema into two parts, with theos (God) now referring to the Father, and kyrios (Lord) referring to Jesus Christ the Son.1

I have worked through this in a number of posts (see below), probably not always ending up in quite the same place.2 What I will suggest here—not for the first time, but perhaps more firmly—is that it was a mistake to find the shemaʿ in the passage in the first place.

There is no God but one

Paul is dealing with a question about the consumption of food that has been sacrificed to idols (1 Cor. 8:1). We have already had a straightforward and definitive statement about the non-existence of idols and the uniqueness of the God of Israel:

we know that there is no idol in the world and that there is no God but one. (1 Cor. 8:4*)

This may echo the Deuteronomic affirmations of one God:

the Lord your God he is God, and there is no other besides him (Deut. 4:35 LXX)

the Lord your God, he is God in the sky above and on the earth beneath, and there is no other besides him (Deut. 4:39 LXX)

the Lord our God the Lord is one. … Do not go after other gods from the gods of the nations around you, because the Lord your God, who is present with you, is a jealous god. Lest the Lord your God, being angered with wrath against you, destroy you utterly from the face of the earth. (Deut. 6:4, 14-15)

But there is no kyrios in verse 4, which seems odd if Paul had meant to include Jesus in the divine identity as expressed in the shemaʿ. Why drop the critical element that identifies the one God as the God of Israel when you are about to reassign it to Christ? The verse reads instead as a generic statement of the oneness of God in contrast to the plurality of the gods of Greece and Rome: “For although there are so-called gods whether in heaven or on earth…” (8:5).

Elsewhere in the Greek scriptures, the uniqueness of Israel’s God is asserted without reference to God as kyrios, as part of a polemic against idolatry, as in 1 Corinthians 8:4, 6a:

Thus says God, the king of Israel, who delivered him, God Sabaoth: I am first, and I am after these things; besides me there is no god. … You are witnesses whether there is a god besides me, and they were not formerly. (Is. 44:6, 8 LXX)

Did not one god create us? Is there not one father of us all? Why then did each of you forsake his brother, to profane the covenant of our fathers? Judah was forsaken, and an abomination occurred in Israel and in Jerusalem, for Judah profaned the sacred things of the Lord with which he loved and busied himself with foreign gods. (Mal. 2:10-11 LXX)

The last passage strikes me as especially relevant because it corresponds closely to the language and thought of 1 Corinthians 8:6 in a number of ways.

1. The prophet says that for “us” who are Israel there is one God, who is the “father of us all,” who created his people. Paul says that for “us” (who are renewed Israel in Christ) there is one God, the Father, who is the origin of this whole new state of affairs. The parallelism is compelling and has further consequences.

2. We see here that it is the threat to the integrity—and future life—of the community that elicits the creational language. Participation in idolatry does not compromise the cosmos; it compromises that people which God has created, and has now re-created through the foolish wisdom of the cross (cf. 1 Cor. 1:18-31).

3. Both texts have a prophetic-apocalyptic orientation. Participation in idolatry and the worship of “foreign gods” is likely to bring judgment on the people which God has created:

The Lord will utterly destroy the person who does this until he has even been humiliated from the tents of Jacob and from among those who bring sacrifice to the Lord Almighty. (Mal. 2:12 LXX)

You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons. You cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons. Shall we provoke the Lord to jealousy? Are we stronger than he? (1 Cor. 10:21-22)

So I conclude: “Jesus has been included not in the divine identity expressed in the Shema but in the divine purpose expressed in an intensifying narrative of conflict, judgment, and rule.”3 Such inclusion is expressed in terms of enthronement and authorisation, and ultimately it is contingent upon the need to judge Israel and defend them against their enemies.

Many gods and many lords

Paul then observes that in the pagan world “there are many gods and many lords.” So rhetorically it is not the invocation of Israel’s foundational confession of the oneness of their God, whose name is YHWH, that introduces the term kyrios into the argument but reflection on the plurality of kyrioi in the pagan world.

It is this distinction between many gods and many lords in the pagan world that provides the rhetorical frame for the two part confession in verse 6. For those of “us” who believe that kingdom and lordship have been given to the crucified Jesus, there are not many gods but one God, who is bringing this whole new order to existence; there are not many lords but one Lord, through whose faithfulness unto death this whole new order is being created.

So to this point we have had no reason to think that the shemaʿ underpins the development of thought. Against Fee, Paul has not kept the “one” of the shemaʿ “intact”; he has controverted the “many” of the pagan acclamations. That is a quite different rhetorical manoeuvre.

Besides, the shemaʿ is not a two part thing to divide between God and Jesus. There is one “person”—yhwh ʾelohim, kyrios ho theos. If Paul splits theos from kyrios in 1 Corinthians 8:6, then we must infer that God is no longer kyrios, YHWH is no longer yhwh: God is the Father only, Jesus has become the kyrios. That is surely out of the question! Much better to assume that the shemaʿ was never there in the first place.

Lords who are kings

The field of reference for kyrios in such a context is easily illustrated. Darius is addressed by a Jew as kyrie basileu (“lord king”) (1 Esd. 4:46). Nebuchadnezzar is “lord (kyrios) of all the earth” (Jdt. 6:4; cf. 11:4). He is acclaimed by the Chaldeans, “O lord (kyrie), king, live forever!” (Dan. 3:8-9 LXX). A king, “who is lord (kyrion) of so many people,” is struck in the face by the daughter of his concubine (Josephus, Ant. 11:54). Josephus says of Antipater that he “desires the shadow of that royal authority, whose substance he had already seized to himself, and so hath made Caesar lord (kyrion), not of things, but of words” (War 2:28). If YHWH is called “God of gods and Lord of lords” (Deut. 10:17; Ps. 136:3; Dan. 2:47 LXX; 4:34 LXX), it is in recognition of the fact that there are many gods and many kyrioi in the pagan world.

So it was common enough in Hellenistic-Jewish usage for a king to be spoken of, even approvingly, as kyrios—a “royal epithet”; and this reflects wider Hellenistic usage. Augustus is called “God and Lord (kyrios) Caesar, Dictator”; Herod the Great is called “King Herod, Lord; likewise, Agrippa I and II are both kyrios basileus Agrippa (TDNT III, 1049-50).

We also have to take into account what is said about the Lord Jesus Christ in 1 Corinthians. He was crucified; he was raised from the dead; he now has a new bodily form by the power of the Spirit (sōma pneumatikon), which his followers expect also to attain (e.g., 2 Cor. 4:13-5:5; Phil. 3:20-21); he has been installed as king, under whose feet all things have been subjected; he was revealed by God to Paul; his Spirit and power are active in the churches; he is confessed as Lord; he will be revealed to the world on a future “day of our Lord Jesus Christ”; he will judge on that day; and in the end, when there are no enemies left, he will give his royal authority back to the Father who bestowed it on him, he will step down, abdicate, “that God may be all in all” (1 Cor. 15:24-28).

In the background, of course, is Psalm 109:1 LXX: the Kyrios who is YHWH and God said to the kyrios who is ʾadon and Davidic king, “Sit at my right hand until I place your enemies as a footstool for your feet.” In the midst of the Nebuchadnezzars and Herods and Caesars of this world, Jesus has been established by YHWH as king to judge and rule, for the sake of his people, until the final enemy has been destroyed.

Nothing in this narrative hints at the assimilation of the person of Jesus to the personhood of the one God, the creator of all things and Father of Israel. Everything is explained by what I am calling the apocalyptic narrative.

A radical paradigm shift

However, because the messianic kingdom given to Jesus was so bound up with the defeat of the pagan nations, with their many gods and many lords, we can understand why a radical paradigm shift was required once that victory was attained. The apocalyptic vision slipped into the past, and the kingdom narrative was re-conceptualised in philosophical categories. Trinitarianism emerged as an accommodation to a classical (not Jewish) monotheism, not a repudiation of polytheism and idolatry. I have no problem with that.

Thank you, Andrew.

A long time ago I heard the view expressed that the Hebrew of the Shema might be better rendered into English as “YHWH is our God, YHWH alone.”

This strikes me as plausible, in view of the OT preoccupation with the problem of Israelite defection to “other gods”. Abstract questions of the nature of the Divine Being are a “thing” in early Christianity but, as I understand it, this seems to not have been a preoccupation of Hebrew religion.

I’m wondering whether this adjustment to the understanding of the Shema modulates your analysis here. I think it’s not unfavorable to it.

@Samuel Conner:

I’m not a Hebrew scholar so I’m not really qualified to judge. The Hebrew runs literally: Hear, Israel, YHWH our God YHWH one. It seems to me that it makes more sense to translate, “YHWH (is?) our God, YHWH is one,” than “YHWH our God is one YHWH.”

It is certainly directed against the worship of many gods:

You shall not go after other gods, the gods of the peoples who are around you— for the LORD your God in your midst is a jealous God—lest the anger of the LORD your God be kindled against you, and he destroy you from off the face of the earth. (Deut. 6:14-15)

But I would have thought that the point is that Israel must serve only one God, who goes by the name of YHWH, rather than that he is a God “alone”—the implication being that other gods do not exist? Or is that what you’re getting at?

In any case, I struggle to see how the Shema can be divided between “God” and YHWH so that Jesus is understood to be the YHWH-Kyrios person. YHWH is a name. I could say, “Peter is my boss. Peter is my one boss.” Would it be meaningful then to assign the name Peter to someone else and claim that my boss actually consists of someone who is no longer called Peter and someone else who is now called Peter?

First, the appeal to 1 Cor 8:4 (“there is no God except one”) as generic rather than Shema-inflected overlooks the double-echo structure that shapes vv. 4-6 as a single argumentative unit. Verse 4 establishes the polemical thesis that pagans’ so-called deities are ontologically null; verse 5 concedes, in paromastic style, that “there are many gods and many lords”; and verse 6 answers both clauses chiastically. The narrative hinge is precisely the monotheistic confession of Deut 6:4, whose semantic content is transposed but whose cadence is retained: “for us, one God … and one Lord.” The Shemaʿ begins with Israel’s self-designation (“Hear, Israel”); Paul substitutes “for us,” delimiting the covenant people re-constituted in Christ. Likewise, the conspicuous relocation of κύριος to the Christ-clause does not “drop the critical element” but dramatizes its reassignment: the title that in the LXX renders יהוה is now part of a bipartite ascription in which θεός and κύριος together name the singular God, while simultaneously distinguishing Father and Son. The resultant formulation is not an abandonment of the tetragrammatic identity but a christologically expanded reprise—what Bauckham has aptly labelled a “christological monotheism.”

Second, the Mal 2:10–11 parallel, though rhetorically striking, cannot bear the exegetical weight placed upon it. Malachi invokes the single creator-God as the ground of intra-Israelite fidelity, but no second predicate comparable to Paul’s εἷς κύριος is present, nor any cosmological pre-existence christology. Paul’s addition of the mediatorial ἐξ οὗ…δι’ οὗ schema (cf. 1 Cor 11:12; Rom 11:36; Col 1:16) is decisive: he places the Lord Jesus on the divine side of the Creator–creation divide, assigning to him the instrumentality of origination that Jewish wisdom and Logos traditions reserve for God’s own hypostatic activity. This considerably exceeds Malachi’s covenantal protest, and it does so in confessed continuity with the Shemaʿ, not in conceptual isolation from it.

Third, the argument that κύριος in Greco-Roman usage commonly functions as a royal epithet proves too much and too little. Too much—because in the LXX κύριος has undergone a semantic elevation precisely by becoming the standard surrogate for the divine name; its new theological freight cannot be neutralized by appealing to mundane honorifics. Too little—because Paul couples κύριος with the cosmic preposition διά, thereby identifying Jesus not merely as a ruler but as the ontic mediator “through whom” all things came to be and through whom Christians exist. Nothing in Hellenistic titulature for Roman emperors remotely approaches this cosmological scope. To collapse Paul’s language into the generic is to flatten its polemical and doxological edge.

Fourth, the claim that Paul’s christology is an ad hoc prophetic-apocalyptic expedient awaiting “a radical paradigm shift” after the church’s victory over paganism misreads both chronology and conceptual genealogy. Trinitarian logic did not arise from a later Hellenistic domestication of an erstwhile low christology; rather, it emerged as the church’s synthetic exegesis of data already present in the apostolic proclamation—cosmological agency, liturgical invocation, baptismal triadism, doxological parity—all of which the Corinthian correspondence amply displays. The so-called “Greek philosophical categories” that feature in the fourth-century debates were recruited precisely to safeguard the biblical claims: the Nicene homoousion is a conceptual clarification, not a conceptual innovation.

Finally, Paul’s doxological praxis refutes the suggestion that Jesus remains outside the purview of cultic worship. In 1 Cor 1:2 the church calls upon (ἐπικαλουμένοις) “the name of our Lord Jesus Christ” in a phrase whose Septuagintal resonance (e.g., Gen 4:26; Joel 3:5 LXX) unmistakably denotes cultic address to the deity. Similarly, the Maranatha acclamation (1 Cor 16:22) is not a mere request for eschatological intervention parallel to angelic petitions; it is a prayer for the parousia of the κύριος himself, presupposing his sovereign authority over times and seasons. These cultic patterns, attested within twenty-five years of Easter and embedded in communities that included Torah-confessing Jews, testify to a striking expansion—not a negation—of Jewish monotheistic devotion.

In summary, the attempt to excise the Shemaʿ from 1 Cor 8:6 and to restrict Paul’s christology to an exalted-but-created regency underestimates the text’s intertextual finesse, misconstrues its rhetorical symmetry, and fails to account for its liturgical and soteriological implications. The verse stands as one of the earliest data points for a christologically reformulated monotheism: Father and Son are jointly confessed within the unique divine identity, yet personally distinguished—a pattern that the later church, with inevitable philosophical elaboration, would articulate in Trinitarian dogma without betraying the Jewish-scriptural matrix from which it sprang.

@X. József:

Another solid rebuttal. Thank you. Nevertheless…

1. You have misunderstood my point about dropping the critical element. My question is: why is there no kyrios in 1 Corinthians 8:4 if Paul means then to distribute the terms of the Shema between God and Jesus? That is why I think it less than certain that “no God but one” alludes specifically to the Shema. In the Greek form of the Shema, the word kyrios appears twice, including in prominent first position in the confession—indeed, it is the subject of the Shema, it’s what it’s about: kyrios ho theos hēmōn kyrios heis estin.

If Paul is about to make the sort of christological-monotheistic reassignment that scholars like Wright and Bauckham describe, why does he not include kyrios in verse 4? Arguably because the kyrios-YHWH reference would conflict with the kyrios-ʾadon thought that is actually at work in verse 6.

So there is no “conspicuous relocation of κύριος”—the word is conspicuous only by its absence; it’s not there to relocate. The “narrative hinge,” if we want to put it that way, is the recognition that pagans have “many gods and many lords.” That’s what gets us from “one God” to “one God” and “one Lord”; that’s where the term kyrios comes from in Paul’s argument—explicitly—not from some purported reference to the Shema; and it’s what determines the rhetorical structure of verse 6.

2. Agreed: there is only one divine actor in Malachi 2:10-12. But there are two actions. First, God is the “father” who created (ektisen) Israel. Secondly, God is the kyrios who will judge idolatrous Israel.

This narrative accounts very well both for the distinction between Father and Lord in 1 Corinthians 8:6 and for the creation language. On the one hand, God has delegated to the kyrios-ʾadon seated at his right hand the authority to judge and rule over his people in the midst of the nations—not least when they get entangled with idolatry (cf. 1 Cor. 10:14-22). On the other, this is a people that has been re-created (ex hou) by the Father through the agency (di’ hou) of Jesus.

So what Paul has done is not place Jesus “on the divine side of the Creator-creation divide”; he has transferred divine authority, fully in keeping with the testimony of the entire New Testament, to the Jesus side of that divide.

3. The key LXX text is Psalm 109:1: ‘The kyrios who is YHWH said to the kyrios who is ʾadon, “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.”’ This give us ample reason not to equate kyrios with YHWH in 1 Corinthians 8:6, especially since Paul did not see fit to include kyrios in his affirmation of the oneness of God in verse 4. Paul’s contention is that the one now acclaimed as kyrios-ʾadon is the one through whom Israel has been re-created. Nothing objectionable about that.

4. This is the point at issue. You can’t just beg the question like that.

@Andrew Perriman:

Your clarifications help to locate the precise crux of disagreement, but they do not, I think, dislodge the cumulative evidence that Paul has reread the Shema christologically. A Trinitarian appraisal accentuates three interconnected phenomena: intertextual syntax, prepositional cosmology, and cultic invocation. Re‑examining these in the light of your four rejoinders confirms rather than weakens the high‑christological reading of 1 Cor 8:4‑6.

Paul’s rhetoric in verses 4‑6 is dialogical. In v. 4 he cites the Corinthian slogan (“we know…”), endorses its monotheistic core, yet reserves the term κύριος for his own corrective exposition. The omission is therefore wholly strategic: the community’s knowledge, though formally orthodox (“no god except one”), is functionally deficient because it has not assimilated the risen Jesus to that confession. Paul will supply the deficiency in v. 6, but only after exposing the cognitive dissonance between the Corinthians’ monotheistic maxim and their pragmatic accommodation to πολυθεΐα. The literary device—quotation, concession, augmentation—depends precisely on deferring κύριος until the decisive antithetical moment. Its subsequent placement (ἡμῖν… εἷς θεός…, καὶ εἷς κύριος…) answers, clause for clause, the many‑gods/many‑lords of v. 5 and thereby signals an intentional recasting of the Shema rather than a generic paraphrase of Deuteronomic monotheism.

Malachi 2:10‑12 cannot furnish the matrix for Paul’s formulation. First, its dual actions remain intradivine: the same YHWH creates and judges. Paul, however, distributes creative prepositions between Father (ἐξ οὗ) and Son (διʼ οὗ), a differentiation irreducible to a simple agency/authority model. Second, Malachi lacks any hint of bipersonal cult; by contrast, Paul’s letters repeatedly synchronize the confession, worship, and eschatological hope of the churches around the titular pair θεός‑κύριος (1 Thess 1:1‑3, 9‑10; 2 Thess 1:1‑2, 12; Rom 1:7; 2 Cor 13:13), culminating in shared doxology (Rom 16:27 with 16:24 L‑text). Third, Malachi’s ἐκτίσεν refers to covenantal formation, whereas Paul’s πάντα διʼ αὐτοῦ in 1 Cor 8:6 parallels the cosmic scope of Col 1:16 and Heb 1:2‑3—texts that likewise embed Christ within the archetypal Creator’s prerogatives.

Psalm 110 (LXX 109) indeed distinguishes between YHWH and ʾādôn, yet the early church’s reception of the psalm repeatedly collapses that distinction christologically. Peter at Pentecost applies τὸν κύριον in v. 34 to Jesus (Acts 2:34‑36). Hebrews 1:10‑12 quotes Ps 102 LXX, addressed to YHWH, as speech to the Son, thereby treating κύριος interchangeably across the divine‑Son nexus. Paul, for his part, aligns Isa 45:23’s exclusive oath to YHWH with the universal homage due τῷ κυρίῳ Ἰησοῦ in Phil 2:10‑11. This hermeneutical trajectory confirms that κύριος in early Christian exegesis is not rigidly tethered to either the tetragram or to merely royal human lordship but functions as the shared covenantal name of the one God now revealed dyadically.

Most decisive is Paul’s cosmological choreography. The triadic origin‑mediator‑goal formula (ἐξ οὗ… διʼ οὗ… εἰς αὐτόν, cf. Rom 11:36) belongs to Jewish God‑talk; when Paul inscribes Jesus into that slot, he positions him ontologically, not merely functionally, on the Creator side of the creation divide. Authority can be delegated; creatorial causality cannot. By attributing περιέχειν τὰ πάντα διʼ αὐτοῦ to the exalted Christ, Paul predicates of the Son a participatory role in the divine prerogative that Second‑Temple literature consistently attributes to personified Wisdom or to the hypostatic Logos—entities that, though distinguished from the Father, are nonetheless intrinsic to his identity, not extrinsic agents. Paul’s wording thus anticipates, rather than awaits, Nicene homoousian logic.

Finally, cultic invocation seals the argument. The Corinthian formula προσεκαλεῖσθε τὸ ὄνομα τοῦ κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (1 Cor 1:2) employs Septuagintal theophoric diction (“call upon the name”) reserved for Israel’s deity. The Eucharistic epiclesis (1 Cor 11:26) announces the Lord’s death “until he come,” integrating remembrance, proclamation, and future advent within one kuριακὸν δειπνο͂ν. Such practices exceed the veneration of a vice‑regent; they express worship of one who, together with the Father and Spirit, receives the church’s prayer, allegiance, and eschatological hope. Trinitarian theology does not inaugurate but explicates this pattern.

Therefore, the absence of κύριος in v. 4 is a calculated pausal feature, not evidence against Shema allusion; Malachi’s intra‑YHWH pair of verbs cannot explain Paul’s ontological bifurcation; Psalm 110’s two‑lords reading is recast, not contradicted, in primitive Christian exegesis; and the cosmological‑cultic fusion of v. 6 indelibly marks Jesus as intrinsic to the μοναρχία τοῦ θεοῦ. Paul’s christological reformulation of Israel’s confession remains the wellspring from which later Trinitarian dogma legitimately draws.

In John 17:3, Jesus Christ himself identifies the “father” (vs 1) as “the only true God.” In Mark 12:29, Jesus quotes the Shema, “…the LORD our God is one LORD.” I think it highly uncharitable to Paul to think that he would contradict Christ.

@Larry Thrasher:

I don’t see the problem, Larry. Paul asserts the oneness of Israel’s God in 1 Corinthians 8:4-6, as Jesus did. But that assertion is not necessarily directly dependent on or an allusion to the Shema. Yes, we can always say that the Shema is in the background somewhere, but there are other biblical traditions that may account for Paul’s language—and more importantly, for his argument in this passage.

Recent comments