A reconstructed “Hymn of Babylon,” partially recovered from ancient cuneiform tablets with AI, reveals rich praise for Marduk, Babylon, its temple Esagil, and the Babylonians. Dating to around the 13th century BC, it includes vivid imagery of a city adorned with precious stones, echoing the biblical vision of heavenly Jerusalem. The hymn emphasizes Babylon’s charity and respect for foreign priests, paralleling biblical values of justice and inclusion. This portrayal may have influenced Jewish religious architecture and Christian theology. The article concludes that the church must again reimagine a just, monotheistic community in light of a now-faded Christian civilization.

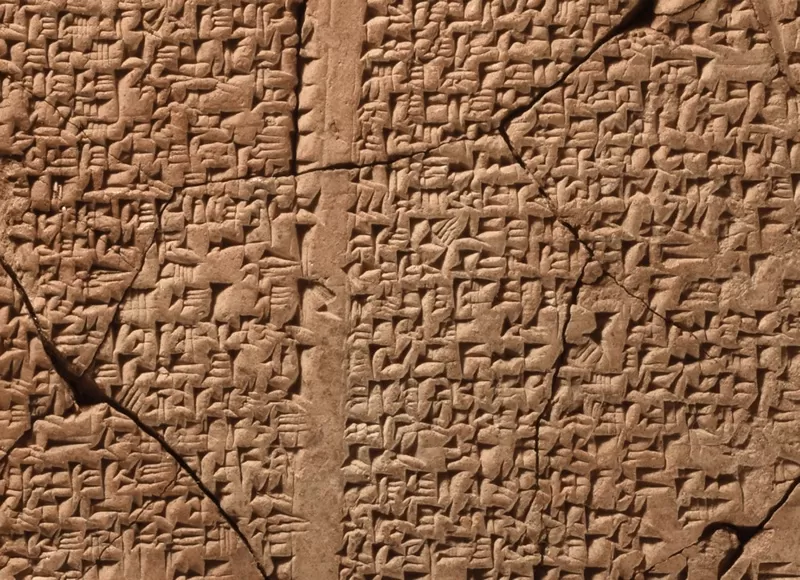

The publication of a reconstructed “Hymn of Babylon” has been in the news. The text of the hymn has been assembled from a number of cuneiform tablets from the Sippar library with the help of AI. The hymn is incomplete; it would have been about 250 lines in length, roughly two-thirds has been recovered. The work may date to the 13th century BC. It is made up of hymns to Marduk, to his temple Esagil, to Babylon the city and its river, and to the Babylonians. The authors of the article in Iraq journal say:

It contains unparalleled descriptions of the healing powers of Marduk, the splendor of Babylon, the spring borne by the Euphrates to the city’s fields and—most extraordinary of all—the generosity of the Babylonians themselves.

A couple of things caught my eye—a little at random, but they tell a story.

A city made of precious stones

The description of Eridu or Babylon as a city thickly encrusted with precious stones is reminiscent of the account of the heavenly Jerusalem in the book of Revelation.

Bolt of carnelian, gate of […],

Inlaid ring, treasure chest of […],

Obsidian, lapis lazuli, agate, and mountains of […],

(And) precious jasper—gem of sovereignty. (105-8)

The wall was built of jasper, while the city was pure gold, like clear glass. The foundations of the wall of the city were adorned with every kind of jewel. The first was jasper, the second sapphire, the third agate, the fourth emerald, the fifth onyx, the sixth carnelian, the seventh chrysolite, the eighth beryl, the ninth topaz, the tenth chrysoprase, the eleventh jacinth, the twelfth amethyst. And the twelve gates were twelve pearls, each of the gates made of a single pearl, and the street of the city was pure gold, like transparent glass. (Rev. 21:18-21)

Perhaps that adds weight to my suggestion that in the second vision (Rev. 21:9-22:5) the heavenly Jerusalem is the historical “institution” that would supersede “Babylon the great,” which was pagan Rome—a holy and righteous city of the living God in the midst of the nations.

Foreign priests

But it is the portrayal of Babylon as a “paragon of almost social-democratic charity” that seems especially to have got people’s attention:

Bathed priests of Ištaran, pure priests of Šamaš,

Buḫhlû-priests of Šušinak, Nippureans of Enlil —

The foreigners among them they do not humiliate.

The humble they protect, their weak they support,

Under their care, the poor and destitute can thrive.

To the orphan they offer succor and favor,

The prisoner they set free, the captive they release (even) at the cost of a silver talent,

With the absent person they share the inheritance,

Piously observing, they return kindness.

They follow the gods’ command, and justice they keep,

The original stele, the ancient law.

The hosts of righteous Ningirsu, of sweet Alala,

They abstain from insulting, honoring and praising each other.

In acquisition they are appropriate, in reflection they bring delight,

They brighten up the mood, and revel in merriment. (133-47)

Much of this is echoed in the Jewish scriptures. YHWH “executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing” (Deut. 10:18).

But the “foreigners” in the Hymn of Babylon appear to be foreign priests. The authors of the article state: “The concept of respecting the foreigners has, of course, Biblical connotations, although in our text the foreigners referred to are specifically the foreign priests living in Babylon.”

In that case, a better parallel may be the assurances given to the “foreigners” (Babylonians? other immigrants?) who had attached themselves to the Jewish community in Babylon and now feared exclusion on the return of the exiles to the Jewish homeland:

And the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD, to minister to him, to love the name of the LORD, and to be his servants, everyone who keeps the Sabbath and does not profane it, and holds fast my covenant—these I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples. (Is. 56:6-7)

So perhaps the Babylonian embrace of foreign priests became paradigmatic for the inclusive architecture of Herod’s temple, with its immense court of the gentiles and then for the life of the church as a priestly people consisting of Jews and of incomers from the nations.

Reworking the model

Out of the social-religious materials of the Ancient Near East the priestly Israelite community fashioned a model of a disciplined, just monotheism, embodied in the institutions of the nation—land, Law, monarchy, temple, prophethood.

In the long run, the model proved to be impracticable and unsustainable. The house of prayer for all nations became a den of robbers and was destroyed.

The New Testament describes the traumatic process by which the model was reworked and presented to the Greek-Roman world as the pattern for a new priesthood, subject to Jesus Christ, the priest-king in the presence of God, empowered by the Spirit, for the age to come—a holy city, a new Jerusalem, in the midst of the nations.

The Church Fathers did the detailed design and construction work for a post-Jewish, post-pagan worldview and civilisation.

That civilisation and worldview are now largely derelict, and the church is again having to rework the model of a disciplined, just monotheism upheld by a dedicated priestly community, subject to Jesus Christ, empowered by the Spirit of the living creator God.

Recent comments