The doctrine of the imago Dei has often been overextended beyond its biblical foundations. In Genesis, humanity is made in God’s image, not as another kind of animal but with godlike capacity for social organisation and dominion. This distinction persists through generations and after the flood, grounding the sanctity of human life, but it is never depicted as lost or damaged by sin. In the New Testament, “image” refers not to humanity generally but to Christ specifically as the risen Lord. Believers are conformed to his image through suffering and resurrection, making “image” an eschatological, not anthropological, category.

The standard argument about the “image of God” is that 1) humanity was created, male and female, “in the image, according to the likeness” of God; 2) this “image” somehow encapsulates the essential nature and dignity of humanity; 3) the image was broken or lost in the “fall”; 4) it was reinstated in the perfect humanity of Christ; and 5) believers are being progressively conformed to the reinstated image of God in a new creation.

I have been reading Lucy Peppiatt’s excellent introduction to the topic, The Imago Dei: Humanity Made in the Image of God (2022), which covers the biblical material, the history of the development of the doctrine in the western tradition, and its modern theological permutations.

The book makes the whole debate very accessible, but it illustrates the problem that reflection on the matter has drifted a long way from the texts. I will suggest here—In a rather patchy fashion—that the thick line drawn by theologians from the creation of humanity in the image of God to the New Testament motif of the image of Christ quite badly distorts the biblical argument.

In the image and according to the likeness of God

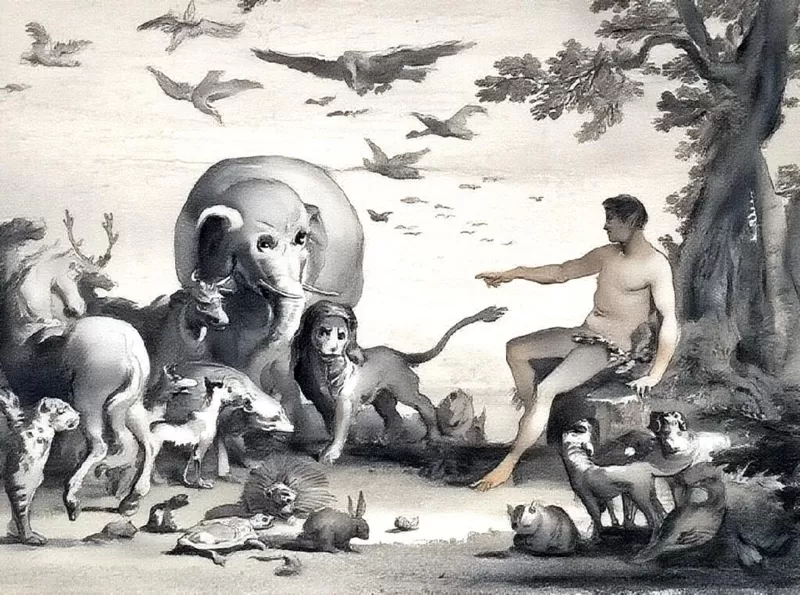

God makes living things “according to their kinds” but he makes humanity “in our image, according to our likeness” (Gen. 1:26-27). Animals are defined by their difference from other animals: a sheep is of a different kind to a bear or a lizard. Humanity is not another kind of animal. Humanity is made according to a divine pattern.

The intrusive plurals in verse 26 open up the possibility for people to be defined not only collectively as ʾadam but also individually, as having godlike capacity insofar as they are superior to the animals. God speaks in the singular, but in his deliberations he says, “Let us make _ʾadam_ in our image, according to our likeness….”

We are not told where the plurality comes from. Does it echo the polytheistic environment of the original accounts? Does God address the divine council? But the point is that it differentiates within the species, so to speak; the ʾadam is not just another undifferentiated genus.

We then revert to the singular for the creative action: “And God created the ʾadam in his image, in image of God he created him, male and female he created them.”

Because humanity is not another kind of animal but has a godlike capacity for social organisation, it is in a position to subjugate and rule over all other living creatures. “Stewardship” is a modern euphemism for expressions that in their biblical context connote conflict and violence. For Ben Sirach, being in the image of God is associated with having “strength,” as God has, to inspire fear in other creatures, to have dominion over beasts and birds (Sir. 17:3-4).

I also don’t think that the kingship motif has any relevance here. Kingdom is a political idea, it has to do with kings and nations. We are not there yet.

In the Eden story, the same ontological distinction between the human and other living creatures is expressed in the work of naming. Adam names the animals but finds no suitable counterpart. The woman, however, is “bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” and is “called Woman, because she was taken out of Man” (Gen. 2:18-23).

At the beginning of the “book of the generations of Adam,” the original determination of humanity in the image and according to the likeness of God is transmitted to the next generation: “Adam lived 130 years and he fathered according to his likeness, in his image, and called his name Seth” (Gen. 5:3*).

The only other reference to the “image of God” is found in the instructions given to Noah after the flood, as part of the renewal of the created order:

Nevertheless, your blood for your soul I will seek, from the hand of every living thing I will seek it and from the hand of the ʾadam, from the hand of a man his brother I will seek the soul of the ʾadam. The one pouring out the blood of the ʾadam, by ʾadam will his blood be poured out, because in image of God he made the ʾadam. (Gen. 9:5-6*)

The flood was a judgment on the descent into violence which began with Cain’s murder of his brother Abel (Gen. 4:1-16; 6:11-13). To guard against the recurrence of such lawlessness a “law” is imposed: violence will be met with violence. Wenham comments: “It is because of man’s special status among the creatures that this verse insists on the death penalty for murder.”1

The Old Testament does not attempt to give content to the idea that the ʾadam was made in the image and according to the likeness of God. All that we can infer contextually is that humanity has enough in common with God to set it apart from and give it dominion over the animals. A ceiling is immediately put on this superiority by the command to be “fruitful and multiply and fill the land and subdue it” (1:28*; cf. 9:7). Humanity must reproduce and survive in the space occupied by all other living creatures.

There is no loss or impairment of the “image of God” as part of the punishment of Adam and Eve, which is not a “fall” but an expulsion. Death doesn’t change things; the distinction between humanity in the image of God and the animals in their “kinds” is passed on from generation to generation. After the flood, it constitutes the basis for the fundamental and universal right to life—or at least, for the punishment of the person who takes a human life.

Image of God in the New Testament

There is barely another reference to the creation of humanity in the image of God in the Bible. Paul, however, speaks of a “man” as being “the image and glory of God” and of Christ as “the image of God” and “the image of the invisible God.”

In the assembly, a man should not cover his head because he is “image and glory of God”; a woman should cover her head because she is “glory of a man” (1 Cor. 11:7*). This inequality is grounded in the order of creation: the woman was made from the man and for the man (11:8). But Paul says that the man is the image of God, not that he is “in the image of God,” and the association with “glory” suggests that he has in mind the visible or public status of the man in contrast to the private status of the woman. It reflects how the behaviour of men and women was perceived in the ancient world and how that reflected on the reputation of the god worshipped. It has nothing to do with the original definition of humanity as male and female created in the image of God.

The two statements about Christ have reference specifically to the resurrected person.

The Jews have been prevented by “the god of this age” from appreciating the message about the glory of the risen Christ, the one proclaimed by the apostles as Lord, “who is the image of God” (2 Cor. 4:3-5). The “light” of this glory is also “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6). So for Christ to be—again, not to be in—the image of God means that, like the man whose head is uncovered in worship, he reveals something about God, perhaps especially to the Jews.

In the passage in praise of the Son in Colossians 1:15-20, the Son is said to be an “image of the invisible God….” This appears to echo strands of Hellenistic Jewish thought.

- God made the human person to be “an image of his own eternal nature” (Wis. 2:23).

- Philo says that having been granted supremacy over all earthly creatures in imitation of the power of God, man is “a visible image of the invisible nature” (Moses 2 65*).

- Divine wisdom is a “reflection of eternal light and a spotless mirror of the activity of God and an image of his goodness” (Wis. 7:26).

- Wisdom is “the beginning, and the image, and the sight of God (Philo, Alleg. Interp. 1 43). The logos is the image of the invisible God (Confusion 97; Dreams 1 239).

There is a speculative and rationalising component to such statements which would feed into the later philosophical and theological traditions. Paul, I think, is less interested in the anthropological aspect than in the sapiential: the resurrected and vindicated Jesus puts a face to the unconventional wisdom of God expressed in the circumstances of the apostolic mission.

This has important practical consequences.

Conformity to the image of Christ

There is no loss of the image of God in the Old Testament, and there is no renewal or restoration of the image of God in the New Testament. Confusion has arisen because Paul says more than once that believers are being conformed to the image of Christ, or something along those lines; and theological assumptions have led us to conclude that this is the original “image of God” being restored in the believer.

That is a misunderstanding, I think.

Essentially, what Paul is saying is that the apostles and, less certainly, other believers in Jesus are being conformed specifically to the image of the one who suffered, died, and was resurrected before them.

Believers are “fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him” (Rom. 8:17). It’s conditional.

Those who suffer as Christ suffered will inherit with him in the age to come, when Jesus Christ and those in him will receive glory among the nations. So in their “Abba, Father!” moment of anguish in anticipation of suffering and death (8:15), they should know that they are “predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers” (8:29). In this way, Christ becomes firstborn of a family of martyrs.

Those who are resurrected from the dead, therefore, because they have been included in Christ’s experience, will “bear the image of the man of heaven” (1 Cor. 15:49). They have suffered in the corruptible, mortal body of the “man of dust”; they will share the glorious, incorruptible, spirit-body life of the risen Lord.

The persecuted apostles, through their hardships and sufferings, not least at the hands of the Jews, are being “transformed” into the “image” of the Lord, “from glory to glory” (2 Cor. 3:18). This is not any believer being transformed into the perfect humanity of Jesus. This is the suffering Jewish apostle being transformed into the image of the crucified messiah who is now their risen master. It’s progressive because the experience is progressive.

Finally, when Paul says that the Colossian believers must put on the new person, which is being “renewed towards knowledge according to the image of the one who created him,” the thought is again that, under conditions of divine “wrath,” they must be fundamentally Christlike in their thinking and behaviour. The original creation of humanity in the image of God is at most a figure for the much narrower idea that the saints in places like Colossae or Ephesus were being conformed to the image of Christ through the experience of persecution.

Theology needs cutting down to size

The conclusion that Peppiatt reaches is expansive, indecisive, permissive, non-committal:

it is abundantly clear that there is no single, closed definition of the imago Dei to which all might assent. Even if we have a preference for one specific perspective, it is unlikely that one definition will succeed in saying all we might want to say about how humanity images God or where that image lies. The doctrine of the imago Dei is multifaceted and constantly evolving. It corresponds both to what we believe to be true of God and to what we believe to be true of humanity; thus each generation and each culture will develop and revise this doctrine, bringing new insights and perspectives to what this claim means for humanity, for God, and for our relations with one another and the world. (129)

That’s how it’s been, but as so often theology overloads scripture, over-generalises—just over-does it.

The Latin expression imago Dei is obscurantist. It makes the doctrine opaque. It detaches reflection from the Jewish texts. It has become a quasi-technical label for the debate about theological anthropology, erroneously suspended between a couple of biblical pegs: the creation of humanity in the image of God and New Testament statements about Christ as image of God.

The Old Testament idea is restricted in scope and application. It serves to differentiate humanity from other living creatures. It is not affected by the disobedience of the first couple, the expulsion from the garden, and the intrusion of death into the story. It does not come up for discussion later in the Hebrew Scriptures.

In the relevant New Testament texts, “image” is always an eschatological, not a general anthropological, category.

On the one hand, the resurrected Christ in heaven, proclaimed to Jews and gentiles,images the eschatological wisdom and purpose of the God of Israel at the end of the age of second temple Judaism, at the dawn of a Christian civilisation.

On the other, those who will suffer and die on his account are being conformed to his image and ultimately will bear the image of the man of heaven in that they too will be raised from death to reign with him throughout the coming ages.

That, I think, is about the extent of it.

- 1

G. Wenham, Genesis 1-15 (1987), 194.

I haven’t read Peppiatt’s book (yet), so I don’t want to comment on that. I do appreciate the observation on 1 Corinthians 11 that Paul may be thinking of “the visible or public status of the man in contrast to the private status of the woman”. This very socially pragmatic, functional (?) perspective is certainly not how “we” normally (what a loaded word) read such texts. I met something similar in Talbert’s discussion of the household code passages in Ephesians and Colossians (see his Paideia commentary Ephesians and Colossians) in the context of the private and public functions of the households (or “household management”), in which the “norms” of being followers of Jesus intrude on this order even as it maintains it as an outworking of witness (p. 149–157, 231–238). I am not equipped to offer a for/against for Talbert’s take, but I appreciate him trying to root the texts in the sociological realities of the time. “Theology overloads scripture, over-generalises—just over-does it”, as you say. But that overloading seems to be our norm, which I am still learning to unlearn.

Thanks for this piece, and for that reminder.

@Russ Herald:

Hi Russ. Thanks for this. I think I would agree with Talbert. Paul neither endorses nor seeks to overturn the patriarchal social order, rather he teaches the churches how to honour Christ, etc., within the system—presumably because he believed that the form of that world was passing away.

By the way, I don’t deny that we need some measure of theologising . The challenge is to ensure that our theology does not obscure ancient biblical arguments and ideas and that it enables us to talk meaningfully about our present.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

It’s interesting to consider Paul’s (and I’d add Peter to that) focus within the idea that the current world was passing away. That itself is a form of theologising.

I got/get your point about theology, and fully agree.

@Russ Herald:

Yes, it is a form of theologising—the theological interpretation of history. I think it’s what we should be doing as the present form of our world passes away.

Recent comments