I spent last week teaching at a church family camp in Belgium on the theme of “Making space for God in post-Christian Europe”. It was a great opportunity to think through, with a highly motivated but marginalized group of people, how a narrative-historical approach to the New Testament might help us to rethink our response to the overwhelming challenge of secularism. This is brief summary of the main points that I wanted to get across.

We began by talking about the crisis as it is experienced by the evangelical churches in Flemish-speaking Belgium, wedged uncomfortably between the formerly dominant Catholic Church and an increasingly aggressive secularism. On the one hand, the identity of the evangelical churches has been determined to a large degree by a rigorous anti-Catholicism: many of their members are converts from the Catholic Church and regard it as the great prostitute, Babylon. On the other, they are painfully aware that their young people are finding it very difficult to keep believing in a culture that is so hostile to faith. In an article in The New York Times (“A More secular Europe, Divided by the Cross”) Andrew Higgins quotes Gudrun Kugler, who is director of the Observatory on Intolerance and Discrimination against Christians:

“There is a general suspicion of anything religious, a view that faith should be kept out of the public sphere,” said Gudrun Kugler…. “There is a very strong current of radical secularism,” she said, adding that this affects all religions but is particularly strong against Christianity because of a view that “Christianity dominated unfairly for centuries” and needs to be put in its place.

One way or another, this situation accounts for the reluctance of the churches to depart from a very narrow and conservative understanding of their task.

Crisis, church and scripture

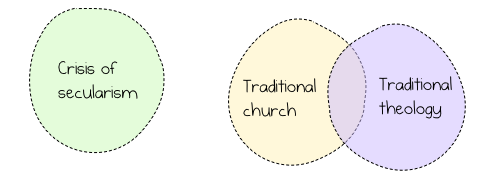

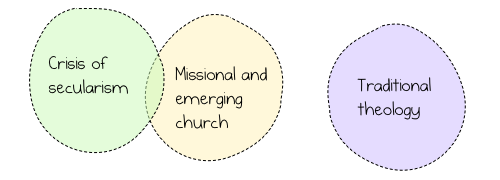

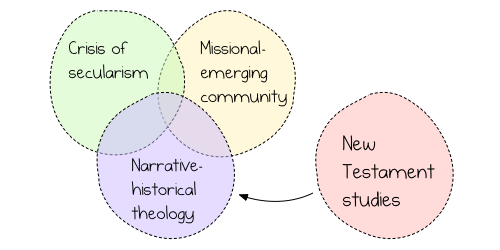

I put forward a simple schema for understanding how the church has responded to the crisis over the last ten years or so.

1. The traditional evangelical church, with its traditional evangelical theology, has had little idea how to address the crisis.

2. In the English-speaking world, over the last decade, two broad, interdependent developments have shifted the sphere of church life and practice leftwards (in the diagram) towards a direct engagement with the crisis faced by the church in the West. First, the emerging church has sought to recover a broad-based authenticity—spiritual, cultural, relational, ethical, intellectual. Secondly, the missional church movement has helped the church as community to re-engage with the world on the basis of this recovered authenticity.

These developments have certainly provoked some quite intense theological debate (notably over such controversial issues as atonement and homosexuality) and have pushed a few isolated, and arguably misunderstood, New Testament ideas into the foreground—mission as incarnation, kingdom of God as social justice, and the popular APEST acronym. But my argument is that this has been driven largely by the circumstances of the social and missional engagement engagement. It is not the result of a hermeneutically responsible reading of scripture. Theology has been left trailing behind to fend for itself.

3. Happily, though, we have also had to reckon with a growing appreciation of the contribution that New Testament studies may make towards the renewal of evangelical identity. As I see it, what has been gained most importantly in recent decades is a sense of how Jesus fits into the narrative of the historical existence of the people of God. Whereas Protestant and modern evangelicalism has typically portrayed him—almost in Gnostic fashion—as a divine redeemer figure who comes into the world to save humanity from its sinful condition, we are now learning to think of him as one who fulfils Israel’s story. Personal salvation is secondary to a political-religious narrative about how God became king at the point of collision between Israel and pagan Rome.

As a result of this, we are in a position to address the challenge of modern secularism on the basis not only of the renewal of community life and mission but also of a “politically” and socially constructed reading of the New Testament. What is at stake repeatedly, from Abraham through to the current crisis faced by the church in Europe, is the integrity of the community of God’s people. This is what the story is all about. It is what a “biblical” theology is all about. We need to get to grips with it.

I’ve got theology like a river in my soul

I suggested that what we need is a river theology that cuts through the unruly landscape of history—that both shapes history and is shaped by history. Not a cloud theology drifting above the landscape of history, only occasionally making contact with a mountain-top moment. We also made quite a lot of the “rollercoaster of the history of the people of God” image, but since I used it recently in another post, I won’t repeat it here.

OK, that looks more like a loch than a river but you get the point.

The justification of a community by faith

We then have to consider how communities of the people of God today should live out of such a retelling of the biblical story.

I made the point that the “gospel” that is proclaimed in the New Testament is not the offer of salvation to individual sinners. It is the affirmation that, in the historical period and context addressed by the New Testament, the God of Israel took control of matters by raising his Son from the dead and giving him an unrivalled authority to judge and rule the nations. Individual sinners certainly had to—and still have to—deal with the implications of that new “reality”. [pullquote]But my argument was that the evangelical churches in Europe today will not survive simply by calling sinners to repentance.[/pullquote] They have to learn to live with reference to the whole narrative of the people of God.

Traditionally evangelicalism has focused on the salvation, faith and justification of the individual person. That needs to change. The New Testament story has to do with the salvation, faith and justification of the community of God’s people. Both Jews and Gentiles would be historically justified because they believed that through the faithfulness of his Son the God of Israel had saved the family of Abraham from destruction.

Similarly today, the fundamental challenge that we face in secular Europe is to believe that God’s people has a viable future. Abraham was counted righteous because he believed the promise that he would be the father of a great nation (Gen. 15:6). He was justified by his faith in the future. Habakkuk was told that in a time of invasion and war—of impending destruction—the righteous person would live on account of his or her faith (Hab. 2:14).

A sign of things to come

I then argued—along the lines of this post—that the mission of communities such as this group in Flanders can be understood, at least in part, as the prophetic embodiment of a hopeful future for the church.

When Jerusalem was under siege by the Babylonian army, Jeremiah bought a field as a sign that God would eventually bring his people back and restore their fortunes:

For thus says the LORD: Just as I have brought all this great disaster upon this people, so I will bring upon them all the good that I promise them. Fields shall be bought in this land of which you are saying, ‘It is a desolation, without man or beast; it is given into the hand of the Chaldeans.’ Fields shall be bought for money, and deeds shall be signed and sealed and witnessed, in the land of Benjamin, in the places about Jerusalem, and in the cities of Judah, in the cities of the hill country, in the cities of the Shephelah, and in the cities of the Negeb; for I will restore their fortunes, declares the LORD. (Jer. 32:42–44)

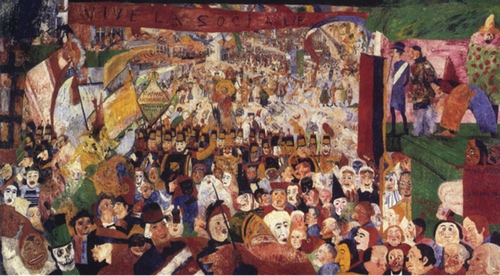

The prophet Jesus acted out the coming political-religious turn-around by riding into Jerusalem in self-conscious fulfilment of Zechariah 9:9. James Ensor’s painting of Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 shows us how that prophetic event may be translated into “modern” terms.

The prophetic community begins with the repudiation—if only in some limited symbolic form—of the controlling idolatries of our culture. It is inspired collectively by the creative Spirit of God to imagine and live out a hopeful future. I didn’t have time to use this quote from Brueggemann but I’ll include it here:

The practice of… poetic imagination is the most subversive, redemptive act that a leader of a faith community can undertake…. The work of poetic imagination holds the potential of unleashing a community of power and action that finally will not be contained by any imperial restrictions and definitions of reality.1

This is not simply a fashionable redesign of church. It is a notion of community that arises out of biblical narratives of crisis. It also underlines the final point, which is that the prophetic community needs to be constructed by its leadership—whatever form that leadership takes—not according to some generic blueprint of church but to fulfil its specific eschatological vocation.

The reputation of God

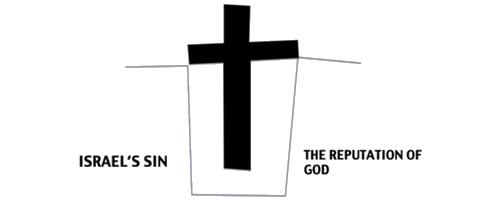

In the last session, we looked at another way of conceiving mission in continuity with the biblical narrative. I posed the question: What would it take from the churches for the reputation of God in secular Europe to be restored? Paul claims that by their behaviour the Jews of the diaspora have brought the name of their God into disrepute among the nations (Rom. 2:17-24). God has acted, however, apart from the Law to demonstrate his “rightness” to the world “through the faithfulness of Jesus Christ” (Rom. 3:21-22; for the translation see “Pistis Christou and Paul’s controlling narratives”).

Jesus made himself of no reputation, took the form of a slave, was executed as a sinner—as a renegade, an apostate, as a false claimant to the throne of Israel—but God raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand to the glory of God the Father (Phil. 2:6-11; Rom. 8:3). So Paul concludes, Jesus became a servant to Israel to show that God is true, trustworthy, faithful to his promises to the patriarchs; and the result was that the reputation of Israel’s God was established among the nations (Rom. 15:8-12).

In the biblical story the gulf bridged by the cross is not between the personal sin and eternal life. It is between the sinfulness of Israel and the reputation of God among the nations. This is the good news—and I think that the churches of post-Christian Europe would do well to construe their own story in similar terms.

- 1[amazon:978-0800619251:inline], 96.

Dear Sir

Read your article with interest. However, let’s answer the question: Why is Christianity fading away? Programs on tv, science, archeology and the like are all indicating truths which go against biblical stories. Adam and Eve were obviously not the first humans…. etc etc. Christianity needs to come clean with science and admit the “errors” in the bible. The message is love, forgiveness and it does not matter whether Adam and Eve were really the first etc etc…. the message of love, forgiveness, thoushalt not…. stays!! Also, Anyone who studies the bible seriously will see that Jesus is not God. God is angry about people misinterpreting the words of Jesus! Jesus always refers to his Father as God, never to himself. Study all Jesus words and you will find the truth. If we keep offending God by creating a second God, we Christians are in grave danger. People are too wise to be fooled any longer. Let’s come clean and God the Father will do the rest through his Son Jesus, yes. Amen. kind regards, Tessa

I always follow your blog and read almost all entries with much interest. I’ve been following NTW for sometime and your narrative-historical approach to the NT seems a promising step toward more robust reading of the NT as an authority as NTW tries to develop in Scripture and the Authority of God—that is Five-Act Theory, I mean.

Now, at the end you linked Gospel and Christendom. How do you evaluate the book in terms of your narrative-historical approach to the NT?

I’m aware of people seeing a Big Shift taking place in the Christian West, e. g. Gordon T. Smith, “The New Conversion: Why We ‘Become Christians’ Differently Today” (Christianity Today, April 18, 2012). How do you see Smith’s analysis of the present crisis/opportunity, though I’m afraid Smith’s analysis doesn’t anyway cover the whole picture and doesn’t go deep enough.

Do you have any thoughts?

@Taka:

Sadly, I don’t really have time at the moment to give you a proper response. My basic view of Wright’s five act play analogy is that it is weighted too much in favour of the narrative of scripture and doesn’t leave enough space for the narrative of the church. It seems to me that the conversion of Rome is no less significant narratively and theologically than the exodus or the exile or the war of AD 66-70. Like wise for the collapse of western Christendom.

I’ll have a quick look at Smith’s article.

Thanks for the questions, though. Appreciated.

The recent initiative of the Archbishop of Canterbury concerning pay-day loans is significant. He plans to let credit unions use churches to hopefully put Wonga out of business. But it transpires that the CofE has indirect investments in Wonga! All of the Welby’s initative seems rather half-hearted and a more radical and costly program is surely called for. Surely a radical return to costly Christianity would sort out so many problems.

@Brian Midmore:

Agreed, but but I’m not that optimistic about a wholesale return to costly Christianity. I would hope that over time the sort of action that Welby is calling for—and other seemingly weak and ambiguous actions—will help shift Christian culture somewhat in a more radical direction. But I think that we probably have to be realistic and accept that the more radical statements will be isolated and to some degree symbolic.

These two related references provide a unique radical critique of the kind of religiosity that is now the norm within the sphere of institutional Christian-ism (and has been for a very long time).

http://www.dabase.org/up-1-1.htm (plus other essays too)

http://global.adidam.org/truth-book/true-spiritual-practice…

Plus two references re the dismal God-less reductionism that mis-informs and limits the usual Christian consciousness

http://www.beezone.com/AdiDa/nirvanasara/chapter1.html

http://www.beezone.com/AdiDa/dreadedgomboo/chapter1.html

Also

http://www.consciousnessitself.org

http://www.dabase.org/Reality_Itself_Is_Not_In_The_Middle.h…

Is Christian-ism really fading?

There are now more Christians in the world than ever before, both in total numbers and as a percentage of the worlds human population.

There is now more Christian propaganda than ever before, both in paper (including the Bible) and electronic forms (including blogs and websites)

There are now more Christian schools and universities. More people reading and writing “theology”. There are now more Christian missionaries than ever before.

And yet the human world is becoming more and more insane every day. Indeed some of the leading edge vectors of this now universal insanity are Christians, especially those that prattle on about “Israel” and its presumed relevance to human life in the 21st century.

@John:

The post addresses the situation in “post-Christian Europe”, where most people have rejected the insanity of Christianity for the insanity of secularism. Things may look rather different from other parts of the world.

Recent comments