In their book What is the Mission of the Church? Making Sense of Social Justice, Shalom, and the Great Commission Kevin DeYoung and Greg Gilbert make a brave and generous attempt to steer the conversation about mission back in a more traditional direction. Many people these days would maintain that the mission of the church is to transform social structures—highlight the plight of the homeless, make poverty history, end human-trafficking, and so on. DeYoung and Gilbert do not dismiss this agenda out of hand—in fact, they have some very positive things to say about it. But they have three concerns about the impact of current “missional thinking”.

What’s wrong with missional thinking

First, they think that perfectly good behaviours sometimes get promoted “in the wrong categories”. For example, they prefer “loving your neighbour” to doing “social justice”, “faithful presence” to “transforming the world”, “living as citizens of the kingdom” to “building the kingdom”. In other words, yes, fine, go ahead and save the planet if you must, but don’t call it mission.

Secondly, they object to the missional zealotry—not quite their words—that requires all Christians to be actively doing something to fix what’s wrong with the world. They think it would be better to “invite individual Christians, in keeping with their gifts and calling, to try to solve these problems”. It’s not mission—these are optional extras—so you can’t insist that the whole church ought to be doing it.

Thirdly, they are concerned that the emphasis on social action risks “marginalizing the one thing that makes Christian mission Christian: namely, making disciples of Jesus Christ”. Call them old fashioned, but “there is something worse than death and something better than human flourishing”.

DeYoung and Gilbert try very hard to be respectful, constructive and even-handed, going so far as to admit that they may well be found among those who pass by the wounded man on the Jericho road. “One of the challenges of this book—probably the biggest challenge—is that we may be seen as (or actually be!) two guys only paying lip service to good deeds” (24). Excellent! There’s a lot of really good reflection along these lines.

But it is clear that they think the missional movement has overstated its case to the detriment of the core vocation of the church, which is to proclaim the good news of Jesus’ “death for sin and subsequent resurrection” and to make disciples in accordance with the so-called “Great Commission”.

You call this a narrative?

I have some sympathy for DeYoung and Gilbert’s critique of the missional movement, but I think that their attempt to reaffirm the traditional model takes us backwards rather than forwards, both biblically and practically.

Their biblical analysis starts off more or less in the right direction with the statement that in order to understand the mission of the church we have to grasp the “grand, sweeping, world-encompassing story that traces the history of God’s dealings with mankind from very beginning to very end” (67). This sort of vague narrative-theological flourish has become a commonplace of popular theologizing.

[pullquote]But at the first junction in the road, instead of following the story straight ahead in the direction it’s going, DeYoung and Gilbert take a short cut.[/pullquote] They think that we understand the story best if we start in the middle, with the death and resurrection of Jesus. But that’s not how narratives work, and it’s certainly not how history works. It’s a lazy way to read scripture.

They ask: “Why do the Gospels focus so squarely on the death of Jesus and his subsequent resurrection?” Because these events answer the question that lies at the heart of the Bible’s story: “How can hopelessly rebellious, sinful people live in the presence of a perfectly just and righteous God?” (68, their italics). This, in their view, is the question which “drives the entire biblical narrative from start to finish”.

The question would certainly identify a key aspect of Israel’s problem, but it is not the biblical narrative that makes this the central issue in DeYoung and Gilbert’s argument. It is the classic evangelical presumption that everything begins and ends with the problem of sin. We would be hard pressed to show how the Old Testament storyline works towards a solution to the problem of how “hopelessly rebellious, sinful people”—notice that they do not say “a sinful people”—live in the presence of a holy God. The storyline—it seems to me—has to do with how YHWH manages his rebellious people in relation to the nations, and the New Testament fittingly begins with the proclamation that the kingdom of God is at hand.

So my main critique of the book would be that DeYoung and Gilbert fundamentally misunderstand scripture in their eagerness to get to the cross and end up with a truncated notion of mission and a weak, individualistic model of discipleship.

Mission and discipleship

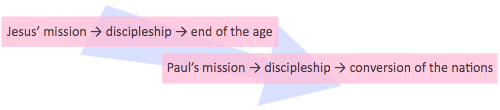

Jesus sent his disciples out to proclaim to Israel and among the nations, perhaps specifically to diaspora Judaism, that God was about to act to judge and redeem his people. They were to make disciples for that eschatological purpose. The task would last until the “end of the age” of the second temple Judaism. I disagree with DeYoung and Gilbert’s traditional reading of Matthew 28:20:

Finally, this discipling task is possible, Jesus reassures his audience, because “I am with you always, to the end of the age”…. Such a far-reaching guarantee would not have been necessary if Jesus envisioned the apostles fulfilling the Great Commission. But a promise to the end of the age makes perfect sense if the work of mission also continues to the end of this age. Jesus’s promise extends to the end of the age just as his commission does. (45)

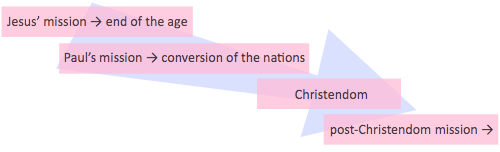

I think Jesus clearly did expect his disciples to fulfil the great commission because he expected the proclamation of this good news throughout the nations, the war against Rome, the vindication of his followers, and the end of the “age” to happen within a generation. DeYoung and Gilbert unthinkingly equate “end of the age” with “end of the world”.

Here’s another example of how disregarding the narrative frame of the New Testament leads to an over-generalized notion of mission:

If you are looking for a picture of the early church giving itself to creation care, plans for societal renewal, and strategies to serve the community in Jesus’s name, you won’t find them in Acts. But if you are looking for preaching, teaching, and the centrality of the Word, this is your book. The story of Acts is the story of the earliest Christians’ efforts to carry out the commission given them in Acts 1:8. (49)

The mission of the apostles in these early chapters in Acts was to continue to warn Israel that the nation faced disaster and to call the people to repentance on the grounds that God had raised his Son from the dead and made him Lord and Christ. A particular historical situation is in view. It is part of a larger narrative, and it is frankly irresponsible to construct a universalized model of mission on such a narrow foundation. These chapters show us one part of what needed to be done in order to renew and transform God’s people before it could fulfil its “mission” to the ancient world. Which brings us to….

The historical task of the churches in the Greek-Roman world was to bear consistent, faithful witness to the resurrection, ascension and sovereignty of Jesus until that time when he would be confessed as Lord not by his disciples only but by the nations. It took about three hundred years. It was a difficult task and required a very demanding level of discipleship.

Throughout the subsequent Christendom period the task of the church ought to have been to mediate the presence of the living God to the nations (a priestly role) and to hold the nations accountable to their confession of Jesus as Lord (a prophetic role). The church didn’t always do a very good job of it and sometimes did a very bad job of it, but that doesn’t mean that the arrangement wasn’t right in principle. Discipleship would have meant training people for that task.

[pullquote]Over the last two or three hundred years the nations have abandoned their commitment to the living God and his Son and have found other gods to worship and other lords to serve, leaving the church in the West not at all sure what its purpose is.[/pullquote] Is it to try and turn the clock back? Is it to maximize private commitment to Jesus? Is it to keep as many people coming to church as possible? Is it to make the world a better place? How do we now justify our existence? I would suggest that there are two basic tasks that face the church today, for which we need to “make disciples”. Whether the word “mission” is strictly appropriate here is another question.

First, the church needs to manage its residual post-Christendom role as a priestly-prophetic community in relation to an increasingly secular-pluralistic society. DeYoung and Gilbert have some interesting things to say about the supposed priestly role of the church, which I may come back on another occasion. The point I would make here is that the church in the West still has a recognized relationship with—and entanglement with—the world which ancient Israel did not have. That’s simply where we are in the narrative.

Secondly, the church needs to imagine and begin to live out a new future for itself. The residual priestly-prophetic role may linger on for some time, like the slowly fading smile on the face of the Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But I think that we are far too complacent about the challenges that lie ahead. The driving force for renewal will come, as in Acts, not from the argument about sin and salvation, but from the deeply challenging and problematic evangelistic assertion that God has raised his Son from the dead and given him all authority. Salvation comes in the wake of that.

What are disciples for?

The point of all this is that making disciples is not an end in itself. We have to ask what we are making disciples for. DeYoung and Gilbert conclude with a definition of mission as going into the world to “make disciples by declaring the gospel of Jesus Christ in the power of the Spirit and gathering these disciples into churches, that they might worship and obey Jesus Christ now and in eternity to the glory of God the Father” (241, their italics). The narrative-historical approach suggests that this is far too generic as a definition of mission. It’s not enough just to be the church. The whole story of scripture is the story of how God works with and in his people in changing historical circumstances. Gospel and kingdom, judgment and salvation, “hell” and heaven, works and grace are not eternal abstractions. They are the terms and concepts by which God’s people made sense of their place in an unfolding story, and I don’t see that things should be any different for us.

Discipleship is not a matter of bringing individuals to the point where en masse they worship God and learn obedience to Jesus. It is how the community of God’s people is formed and maintained to fulfil the historical purposes that the creator God has for it, including, I am quite sure, the prophetic but very practical task of modelling the transformation of human society. In the end, it may be that concrete “missional” engagement, properly interpreted in relation to the dense narratives of scripture and of the church, will speak more powerfully and more convincingly about the future relevance of the living God in the world than more “orthodox” formulations of the gospel in terms of “personal redemption”.

Well said.

“make disciples by declaring the gospel of Jesus Christ in the power of the Spirit and gathering these disciples into churches, that they might worship and obey Jesus Christ now and in eternity to the glory of God the Father”

So here we see the authors’ canon within the canon, the authors’ “gospel” within the implications of the NT wider-framed Gospel, when we read of their misisonal/disciple-making model as defined as growth in ecclesiology. Yet when we read Jesus’ clearer definition of discipliship “teaching them to obey all that…”, we are back to square one as to what he meant, then and now. Mt 5-7 contends to give us a clearer picture of discipleship, arguably, than the common evangelical picture, and that moves us much closer to what you’re vying for here…the transformation of human society. And I fully concur, unless the traditional evangelical prophetic-role decreases (in a post-Christendom climate it falls on deaf ears) and the concrete, impressionable, post-Christendom prophetic role of living in obedience to Jesus’ commands (e.g. Mt 5-7) increases, how can the audience “hear” (or see) the meaning of what is prophesied?

Andrew, I like a lot of what you say here. But for clarification on the comment in your last paragraph:

“Discipleship is not a matter of bringing individuals to the point where en masse they worship God and learn obedience to Jesus. It is how the community of God’s people is formed and maintained to fulfil the historical purposes that the creator God has for it, including, I am quite sure, the prophetic but very practical task of modelling the transformation of human society.”

I’m not sure how these two stand in tension. Modelling the transformation of human society to what end? Wouldn’t it be worship of God and obedience to Christ? In other words, a perfected state of existence? It seems to me that, in line with classic statements like the Westminster Catechism Q1, the “chief end of man” is simply the glorifying and enjoying of God. It’s an end in itself. Or are you simply concered here with a proper definition of discipleship?

@Daniel:

Yes, that was trying to say too much in too small a space. My point was that the Deyoung and Gilbert model of discipleship remains focused on individuals, who are saved, equipped to do whatever task they are called to, and as aggregated individuals worship God. I think that we are actually closer to the New Testament view of things if we think in terms of i) discipling communities, ii) with the particular historical challenges that the community faces in view. I came across this quotation from David Buttrick in an MA essay recently. I think it makes the point well:

Virtually everything in scripture is written to a faith-community, usually in the style of communal address. Therefore biblical texts must be set in communal consciousness to be understood.

Great thoughts here, Andrew. I’ve found that too much of the criticism of the “missional” conversation happens at the surface level, that ends up causing fear-based reactions to terms such as “social justice” and “creation care.”

So I’m curious to know if DeYoung and Gilbert address the starting point of the discussion, the “missio Dei” and the nature of God as a missionary sending God, as revealed in Jesus? Then I wonder if you think it’s permissable to still start with the incarnation as the fullest expression of the missio dei, even if it is taking a bit of a “shortcut,” as your critique suggest? (Granted, this may be confusing a systematic approach vs. a narrative approach.)

@BWellcome:

They have this to say about the missio Dei:

One of the biggest missteps in much of the newer mission literature is an assumption that whatever God is doing in the world, this too is our task. So if the missio Dei (mission of God) is ultimately to restore shalom and renew the whole cosmos, then we, as his partners, should work to the same ends.

They even presume to criticize Christopher Wright on this score.

Personally I think the missio Dei / incarnational theme is overstated, though it has some value as a metaphor for mission. The New Testament over-whelmingly suggests that mission begins not with incarnation but with the resurrection.

Recent comments