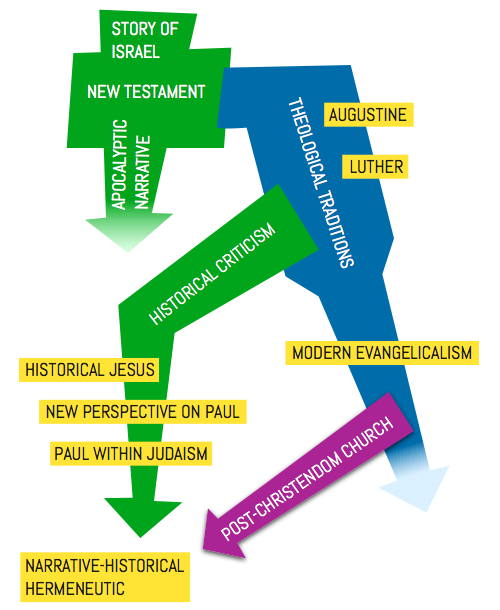

I’ve tried this sort of exercise before, but reading Magnus Zetterholm’s chapter in Paul Within Judaism: Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle has prompted me to have another go at schematising the relation between theology and history and the challenge that this presents to the church today.

We start with the story of Israel. The New Testament is in some respects a climax to this story, but it also projects a narrative future in the language and imagery of Jewish apocalypticism. This narrated future, in my view, consists of judgment on first century Israel in the form of the Jewish War, the faithful witness of the churches in the Greek-Roman world, and the eventual overthrow of pagan Rome and the confession of Christ by the nations of the ancient world.

As this apocalyptic narrative is “fulfilled”, it is replaced by an alternative theologically constructed worldview, the purpose of which is to define and sustain the mind and life of Christendom. Zetterholm presents this narrowly as the “Development of an Anti-Jewish Paul, tracing the story through Augustine and Luther to the “Formation of a Scholarly Paradigm” (Baur, Weber, Bousset, Schürer), in the nineteenth century, which sharply differentiated Christianity from an inferior Judaism. The situation is obviously complex, but it is reasonable to place modern evangelicalism on this theological trajectory.

The rise of historical criticism at the beginning of the modern period led to a radically different perspective on the New Testament material. For the most part the result was extremely damaging for “faith”—the scientific method undermined the credibility both of the texts and of the people and events that they purported to describe.

Over the last fifty years, however, a different scholarly perspective has emerged and gained force. Historical criticism has also had the effect of recovering the historical context for the New Testament narrative. More recent quests for the historical Jesus have suggested that he makes much more sense—is much more credible—when viewed as an actor in Israel’s story.

More importantly for Zetterholm’s analysis, with the publication of Paul and Palestinian Judaism in 1977 E.P. Sanders kicked off a radical revision of the relationship between Paul and second temple Judaism, which has generated the New Perspective on Paul (associated especially with Dunn and Wright), and the “Paul within Judaism” argument, represented by the contributors to this book. The effect is that the New Testament is being more and more tightly re-integrated into the narrative and theological frame of second temple Judaism. This is a major element in what I term a “narrative-historical” hermeneutic.

The final point I would make is that the post-Christendom church will sooner or later have to abandoned the theological paradigm and learn to live and work according to the recovered historical narrative of the people of God. I think it can be done, but as James Mercer observes, the practical challenge is immense. It takes a long time to adjust to paradigm shifts, but I share something of Zetterholm’s confidence:

The binary ideas that Christianity has superseded Judaism and that Christian grace has replaced Jewish legalism, for example, appear to be essential aspects of most Christian theologies. Nevertheless, as in the case with the Jesus, proponents of the so-called Radical Perspective on Paul—what we herein prefer to call Paul within Judaism perspectives—believe and share the assumption that the traditional perspectives on the relation between Judaism and Christianity are incorrect and need to be replaced by a historically more accurate view. It is Christian theology that must adjust, at least learn to read its own origins cross-culturally when demonstrated to be necessary on independent scientific grounds. I am quite confident that Christianity will survive a completely Jewish Paul, just as it evidently survived a completely Jewish Jesus. Religions tend to adapt. (34)

Andrew, from the chart above and the quote “As this apocalyptic narrative is “fulfilled”, it is replaced by an alternative theologically constructed worldview, the purpose of which is to define and sustain the mind and life of Christendom”, would you say that your narrative-historical approach is itself apocalyptic, or that the narrative-historical approach is recuperating where the apocalyptic narrative would have ended up anyway despite the theological traditions’ detour? This is my first time posting and I really appreciate your ministry and the challenges this blog presents.

@Lee Williams:

Hi, Lee. Thanks for contributing. Your question gets to the heart of the matter. I think there are three basic points to make.

First, the narrative-historical approach (New Perspective, Paul within Judaism, etc.) draws attention to the Jewish context of the New Testament. An important aspect of this is the controlling apocalyptic narrative, which prefigures the victory of YHWH over the pagan nations at some point in a realistic historical future. This tends, in fact, to be overlooked by New Perspective, Paul within Judaism, etc., writers.

Secondly, it suggests to me that we can account for the current state of the church by following the story through, from the fulfilment of the original Jewish-apocalyptic expectation, to the demise of Christendom and the struggle of the church to come to terms with its marginalised and discredited position in the world. That is not itself the Jewish-apocalyptic narrative; nor is it a detour. It is simply the historical extension of the New Testament narrative.

Thirdly, this approach may encourage us now to do what the early Jewish-Christian church did—tell stories about our future. We will probably not do so in the idiom of Jewish apocalypticism. We will have to develop our own post-Christendom, post-modern discourse—perhaps the idiom of science fiction. But the underlying “prophetic” pattern will be the same: we respond to the crisis by telling the story that brought us to this point, and by imagining new historical futures.

@Andrew Perriman:

Ok, so if I’m getting my head around this:

The narrative historical approach is a hermeneutic that draws attention to the apocalyptic narrative aspect of the NT which points to a “realistic historical future” victory of Yahweh over the nations. According to the conclusions of the narrative-historical approach, would the “realistic historical future(s)” allude to AD70, Christian conquest of Rome (Constantine), and others (if so, can you give examples), up to an including our own present historical future?

From the second paragraph, how do we describe the “in-between” from Jewish (NT) apocalyptic to the present demise of Christendom? Is this “in-between” period what you call the Theological Traditions? I am trying to understand how, following the chart, the Theological Traditions line was not somehow a detour (corrected by Historical Criticism and the Post-Christendom Church) that a stricter adherence to apocalyptic narrative could have avoided. If I understand correctly your premise is that the correctives from within Theological Traditions are calling us back to reading the NT history apocalyptically and from there extrapolating wisdom for dealing with our own day. Is that close?

Lastly, can you unpack the “idiom of science fiction” for modern discourse a bit more! That’s a completely new one to me! Thank you Andrew.

@Lee Williams:

Ha! I just replied to your response from yesterday before I saw your most recent post…I’ll give it a read.

@Lee Williams:

A new one to me as well, Lee. Pending a response from Andrew I can suggest one from a dramatist’s sort of perspective. This might be clumsy though, I have not thought it through in this context, so much of the idea arises from a very different sort of work.

At root writing good science fiction involves the same skills as good historical fiction, just reprioritized and slightly inverted. At the centre of both types of writing is the ability to create a convincing world from slightly alien (no pun, intended or not) material. All fiction carries this task, but only historical and science fiction genres require breaching the narrative interval, the gap of the strangeness of the data.

Actually all fiction that plays with realism, including fantasy (which is a very serious business in contrast to its name) and psychological thrillers do this as well. Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is an obvious candidate, shifting just one fact — magic is normal but fell out of use and has become merely academic. So is the otherwise fully realistic work of Rupert Thomson as in Dreams of Leaving or The Insult where just one fundamental aspect of normality is made utterly strange and, very importantly, is treated as entirely normal, which makes everything discomfiting.

One of the big mistakes made commonly in science fiction is to fail to imagine the shifted sensibilities that might emerge from that reading of reality, all too often the present emotional intelligence and the ethical aesthetic is simply pressed into service. The other, of course, is the assumption that science fiction is (or has to be) primarily to do with the future. But that, as they say, is eschatology for you.

But this is where I think something might work, and it addresses very much the assertion made in the post that the theological framework of late modernity is going to have to change if we are to negotiate anything like a successful improvisation of a post-christendom future.

The narrative, I believe, is going to return thematically to what it means to be the people of God, communally, socially, ethically, (as you would expect) but also in ways for which we are currently less well equipped, so, imaginatively, creatively, politically, economically. One of the things I have been exploring in this quest for a new trajectory is the huge difference it makes to read the Biblical text forwards, as rigorously as Andrew does. One surprising discovery has been the way the OT people of God narrative becomes so open ended, a truly indeterminate bipartisan relationship. More to the point, the way this narrative, the covenant definitions, the role of the decalogue, issues like Jubilee and so on seem to be geared towards something that we have given so little attention to — the development of the skill to be the people of God. I address some of this in the link at the end of my comment below.

I have no idea if this is anything like what Andrew means, but it has started me thinking.

@Chris Bourne:

Sorry, guys. It will take me a little while to reply to these comments. I’m out and about for a few days.

@Lee Williams:

…and others (if so, can you give examples), up to an including our own present historical future?

No. I think that the New Testament foresaw the conversion of the nations of the empire and the overthrow of an idolatrous imperialism. But that’s in general prophetic terms. I don’t think the New Testament foresaw Constantine as such. Nor do I think that the New Testament has anything to say about what would happen beyond this horizon of the victory of Christ over the pagan gods, except, on the very margins of its vision, that ultimately there would be a final judgment of all the dead and a new heavens and new earth. I don’t take the Preterist line that John’s new creation is still only a metaphor for the restoration of Israel. I think at this point John has in mind an absolute destruction of evil and death.

I am trying to understand how, following the chart, the Theological Traditions line was not somehow a detour (corrected by Historical Criticism and the Post-Christendom Church) that a stricter adherence to apocalyptic narrative could have avoided.

If the point I made above is correct—that the New Testament does not extend the apocalyptic narrative beyond the victory over pagan Rome—then the church in the Greek-Roman world had no choice but to continue the narrative on its own terms. This meant, crudely speaking, as a rather clunky fusion of biblical and Hellenistic thought. They developed a theological system that reinterpreted the apocalyptic outcome—the reign of Jesus at the right hand of God—in a way that made sense to the Greek mind.

Much later, historical criticism showed us just how clunky this fusion was, leading to the recovery of a sense of the New Testament’s relationship to history.

That leaves us having to work out how to continue to live in the light of this whole story, including Christendom and its collapse, having separated out the historical from the theological. I think that the narrative-historical approach to the New Testament gives us new and more realistic ways of thinking about faith, salvation, mission, Jesus, etc. It also gives us a narrative mindset, which I think constitutes a much better basis for responding faithfully to the crisis of secularism.

The “idiom of science fiction” would be one way of imagining a new future—rather as the early church made use of the idiom of Jewish apocalypticism to imagine and give expression to a new future for itself in the world. But I’m not sure I’m the one to start unpacking that. Chris Bourne’s comments certainly take the idea forwards.

@Andrew Perriman:

Not too long ago, a young pastor in training in our congregation was delivering a sermon on the story where some men lower their friend through a roof so Jesus could heal him.

He says, “It must have taken some time to get that hole in the roof. They really could have used a lightsaber and just cut it out. But they didn’t have lightsabers back then. (pause) Nor do we, today.”

I am grateful for this post, and its predecessor, these help enormously just now. I am exploring / practicing ways of developing such narrative formations, allowing for some contribution from aesthetics, as is my wont. To keep this short I will just make one point and attach a couple of references that have also helped.

I have been struck in recent reading by the sheer difficulty of the task facing the early Fathers, as the subsequent generations, in terms of imagining and consolidating Paul’s powerful adoption motif. In particular I am sympathetic to their difficulty after CE70. It is easy to criticize something that was inevitable, the influence of pagan culture and thought, as a sort of purely elective tangent, an act of appropriation which involved heavy redaction of Israel’s narrative, as if supersessionism was a requirement for understanding the end of the temple. Obviously not so, but if not, what?

The problem remained, how could the fathers integrate the nascent gentile church with something that appeared to be disintegrating? (Although I think this rather puts things the wrong way round.) And if that sort of integration was not possible was appropriation not inevitable? And if this is so is some sort of theological drift not inevitably incurred? The point being that changes of trajectory, at first, do not seem that huge but, as with any tangential move, time makes things much more obvious.

The first reference is to an article on First Things by David Bentley Hart. Oddly this appears at first to be simply a piece about Providence. He says, “Hence the need for a generously indeterminate trust in the mysterious workings of God’s will sub contrario. Otherwise the believer is apt to become trapped at one pole in a tedious dialectic of indignant rejection and credulous celebration, indulging either in sanctimonious denunciations of “Constantinianism” or in triumphalist apostrophes to the spiritual greatness of “Christian” culture, in either case reducing the very concept of grace to an empty cipher.”

But he goes on to make the point, “In its first dawning, therefore, the Gospel issued a pressing command, to all persons, to come forth out of the economies of society and cult, and into the immediacy of that event: for the days are short. And, having been born in this terrible and joyous expectation of time’s imminent end—its first “waking moment” being the knowledge that the Kingdom was near—the Church was not at first quite prepared to inhabit time except in light of that glorious crisis. For a people in some sense already living in history’s aftermath, in a state of constant urgency, there was no immediately obvious medium by which to enter history again, as an institution or body of law or even religion. Only after a little time had passed, and expectations had been altered somewhat, would it be possible for this singular irruption of the eschatological into the temporal to be recuperated into a stable order.

Still, of course, the Church quickly assumed religious configurations appropriate both to its age and to its own spiritual content. Jewish Scripture provided a grammar for worship, while the common cultic forms of ancient society were easily adaptable to Christian use. And there was also a certain degree of natural “pseudomorphism” in the process, a crystallization of Christian corporate life (with all its novelty) within the religious space vacated by the pagan cults it displaced. This was inevitable and necessary; a wholly apocalyptic consciousness, subsisting upon a moment of pure interruption, can be sustained for only a very brief period.

The second source is the 2013 Erasmus Lecture given by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. Perhaps the best fifty minutes I have spent online in a while, and very much to our points, I think. The video is here and also on First Things.

Hart’s article is here.

I hesitated to put this final link in because the writing is so preliminary and will change. Always happy for critique though, if anyone feels inclined. But for those who do not know from years ago and pre-post-ost, I am no theologian but am approaching this area as an artist concerned with narrative in social and religious contexts and with aesthetics as a hermeneutic tool, a set of intelligible sensibilities that everyone uses to make sense of things. Here I am experimenting with a form of story for Christians or recently ex, but not really for people for whom an excursion onto Andrew’s site might lead to the need for a clinical intervention.

@Chris Bourne:

Thanks Andrew and Chris for the great posts, and I definitely have some material to look through now! I too am travelling this weekend and don’t have much time to respond. I look forward to continuing the discussion in future posts! Lee.

Recent comments