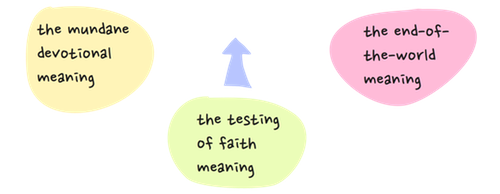

What does Jesus mean when he teaches his disciples to pray “lead us not into temptation”? In a brief appendix (“Jesus’ Prayer and the War of Worlds”) to his book Pure Kingdom: Jesus’ Vision of God Bruce Chilton aims to define a middle ground between two misunderstandings of the petition. On the one side, there is the popular devotional view, according to which “temptation” means “enticement”: we are to ask God to “keep us from wicked impulses”. On the other side, there is the “scholarly view” that Jesus taught his disciples to pray that they would escape the apocalyptic “testing” or “trial” that would come upon them at the end of the world, which was just around the corner.

What the scholarly view has going for it, of course, is the Greek word peirasmos. It doesn’t mean “temptation” in the popular sense. Scholars are not scholars for nothing! Jesus says to his disciples, for example: “You are those who have stayed with me in my trials (peirasmois), and I assign to you, as my Father assigned to me, a kingdom…” (Lk. 22:28–29). He does not mean that they were there when he was beset by sinful thoughts and passions, like the famous Egyptian ascetic, St Anthony.

What he means is that they have (so far, at least) stuck with him despite the mounting opposition from the authorities, and they will be rewarded for it in the age to come. This is the fundamental pattern of Christlikeness in the New Testament, as I’ve argued recently: those who suffer with Christ will be glorified with Christ and will reign with him. So, as Chilton says, “the devotional interpretation, with its general request to ward off bad things, appears imprecise and slack”.

But Chilton thinks that the scholars have also not got it quite right. In Matthew’s version of the prayer, “lead us not into temptation” is interpreted by the phrase “deliver us from the evil one” (Matt. 6:13; Lk. 11:4). Luke doesn’t have that addition, so Chilton concludes that Matthew has embellished the original prayer to give it an intensified apocalyptic slant. He has imposed on Jesus the idea of deliverance from “the devil’s wrath” and a final judgment.

Rejecting both the standard devotional view and the hardcore apocalyptic interpretation, Chilton argues that Jesus draws on a biblical tradition of the “testing of heroes of faith”. The disciples are to pray that their faith will not be tested to breaking point. “It is neither a plea against our own impulses nor a request to be spared an apocalyptic conflict, but the appeal of trusting children to remain with their father whatever might come.”

It’s an attractive idea, not least because it preserves the general relevance of the prayer for the universal church. But I don’t think Chilton’s argument does justice to the wider context either of the Gospels or of the New Testament as a whole. In addition to the saying about the disciples staying with Jesus in his trials, there are three other contexts in which we find the word peirasmos.

1. According to Luke, Satan tested Jesus in the wilderness: “And when the devil had ended every temptation (peirasmon), he departed from him until an opportune time” (Lk. 4:13). The tests are not arbitrary: at issue is how this “Son of God” will gain the authority to rule—ultimately over the kingdoms of the oikoumenē (Lk. 4:5).

2. In Luke’s parable of the sower the seed that falls on the rock are those who “have no root; they believe for a while, and in time of testing (peirasmou) fall away” (Lk. 8:13). This is a parable about the kingdom of God (Lk. 8:10), which means it is about how, sometime in the coming decades, YHWH will intervene to judge and restore his people and put the nations in their place. Testing is something that will happen to people who believe in this new future for Israel.

3. In Gethsamene Jesus tells his disciples to pray that they may not enter into “testing” (peirasmon), and then prays himself that the cup of God’s wrath will be taken from him (Lk. 22:39-46). This is not any old testing of their faith. It is the testing that will come specifically in the course of their mission to Israel in the years leading up to the war against Rome.

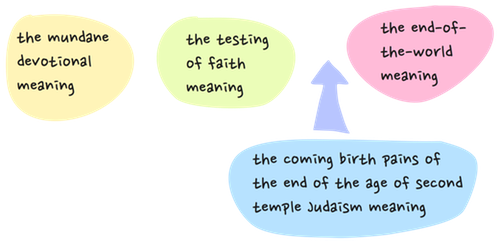

In view of these passages, I would argue for a middle way between Chilton’s middle way and the over-blown, end-of-the-world , “ultimate conflagration” interpretation. I agree that Jesus is not talking about a final judgment. But there is no reason to discount the overarching apocalyptic narrative about the coming kingdom of God. It is made very clear in the Gospels that Jesus expected his disciples to have to take up their own crosses and follow him down a narrow path of suffering until eventually—but within a generation—he would “come” to deliver and vindicate them.

As they went about their mission of proclaiming the coming kingdom of God throughout the empire, they would be given up to tribulation, put to death, and would be hated by all nations. Those, however, who endured through to the end of this time of extreme testing would be saved (Matt. 24:9-14; Mk. 13:9-13).

The concern is taken up elsewhere in the New Testament. James writes: “Blessed is the man who remains steadfast under trial (peirasmon), for when he has stood the test he will receive the crown of life, which God has promised to those who love him” (Jas. 1:12). And Peter: “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial (peirasmon) when it comes upon you to test you…. But rejoice insofar as you share Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed” (1 Pet. 4:12–13; cf. 1:6; 2 Pet. 2:9). Finally, Jesus assures the church in Philadelphia: “I will keep you from the hour of trial (peirasmou) that is coming on the whole world” (Rev. 3:10). In every instance, the eschatological context is unmistakable.

Jesus taught the disciples, who would have to carry his message about the coming intervention of God to Israel and the nations, to pray that God would not lead them into testing. Perhaps he remembered his own testing in the wilderness and wasn’t sure that they would have the same resolve. The petition—indeed, the whole prayer—is explained by the eschatological setting. It is a prayer that YHWH would quickly act to judge his people and establish a new, righteous régime. It all happened a long time ago.

Very helpful, may God grant us the strength to remain faithful no matter what. Thank you.

Recent comments