This is the third short book-length theological response to the coronavirus pandemic that I’ve read. I’ve also looked at John Piper’s Coronavirus and Christ and Walter Brueggemann’s Virus as a Summons to Faith: Biblical Reflections in a Time of Loss, Grief, and Uncertainty.

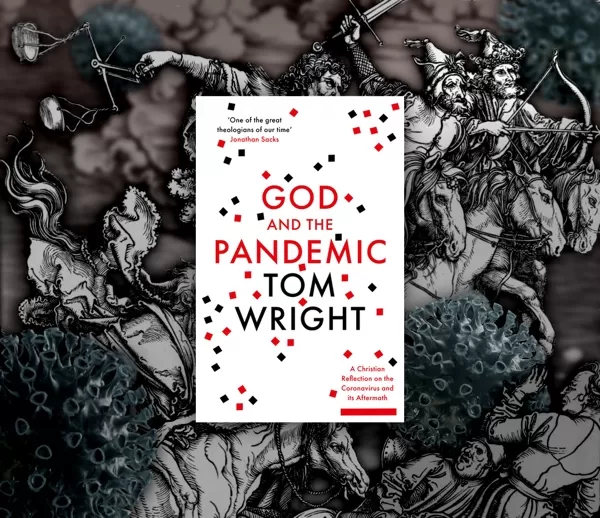

Tom Wright’s contribution, God and the Pandemic: A Christian Reflection on the Coronavirus and its Aftermath, was written to develop the ideas sketched in his Time magazine article. I was disappointed by what struck me as the rather negative tone of that piece. His aim has been to “resist the knee-jerk reactions that come so readily to mind.” Fair enough, but I think he pays a heavy theological and missiological price for such cautiousness, which after all—arguably—is just the other knee jerking.

The central thesis of the book is easily stated: when the “world is going through great convulsions”, the appropriate Christian response is to lament, groan with creation, pray in the power of the Spirit, and serve—especially to serve the poor and defend their interests.

The positive programme, however, is set out repeatedly and expressly in opposition to what he sees as a rash of dubious prophesying around coronavirus. Yes, Amos said that God would reveal what he was about to do to his servants the prophets (Amos 3:7). “Does disaster come to a city,” God says to him, “unless the Lord has done it?” But Wright thinks that we have had too many prophets and religious conspiracy theorists telling us what the Lord is doing.

These range from the cause-and-effect pragmatists (it’s all because governments didn’t prepare properly for a pandemic) to the strikingly detached moralizers (it’s all because the world needs to repent of sexual sin) to valid but separate concerns (it’s reminding us about the ecological crisis).

His method, therefore, is to develop a reading of scripture that downplays prophecy, suppressing the realistic future orientation of so much of the biblical vision and substituting in its place a safe quietism expressed in lament, prayer, and faithful service.

That bothers me. I rather think that the sort of apocalyptic reading of the New Testament for which Wright is famous (ironically) gives us reason and method for developing a theological response that connects the pandemic and the ecological crisis in a compelling modern narrative about the living creator God, who is the God of history.

The book has chapters examining what Wright regards as key texts in the Old Testament, the Gospels, and the rest of the New Testament. The final chapter asks “Where do we go from here?” There is much that is good and wise in it, but my contention here will be that it misses an opportunity—perhaps the best opportunity that the modern church has been given to regain some “prophetic” traction in our age.

The Old Testament

Wright suggests that the Old Testament speaks on two different levels. In the story of Israel Brueggemann’s covenantal quid pro quo is operative: Israel is disobedient, the punishment of exile kicks in, but ultimately God is gracious and Israel is restored. But in some of the Psalms and in the book of Job “there runs the deeper story of the good creation and the dark power that from the start has tried to destroy God’s good handiwork.” According to this story, when we suffer for no apparent reason, “we are to lament, we are to complain, we are to state the case, and leave it with God.”

In Wright’s view, coronavirus belongs in the second story, not the first: it is not punishment for sin, it is merely symptomatic of the inexplicable brokenness of the world.

The problem I have with this is that these Psalms are still part of the story of the covenant people, they do not constitute a different tradition. No text of lament—certainly not the book of Lamentations—exists in isolation from a narrative which finds God at work in large-scale historical events that have significant outcomes for his people.

Even the book of Job, for all its theological obliqueness, does not really question this. The link between righteousness and well-being is stress-tested in extremis, but the whole point of the book is that the mechanism survives the test. Job did not curse God, and in the end the Lord restored his fortunes and “blessed the latter days of Job more than his beginning” (Job. 42:10, 12).

In other words, these two narrative levels cannot be pulled apart quite as easily as Wright suggests. The story of God’s people cannot be disentangled from the thick mesh of stories about nations, empires, and civilisations that makes history—stories of hubris and defiance from Babel, to Babylon, to Babylon the great, to the towering industrial, commercial, and military edifices of the modern world. And vice versa.

Jesus and the prophets

Wright gets the slaughter of the Galileans and the collapse of the tower of Siloam right, though the wrong interpretation would have suited his approach better (Lk. 13:1-5). “Unless the people changed their ways radically, then Roman swords and falling stonework would finish most of them off.” It’s a direct instance of Jesus reading “the signs of the times” (Lk. 12:54-56). “So far, so prophetic. Forty years later, Jesus was proved right.”

But when this evil and adulterous generation came asking for a sign, Wright says, Jesus would only point them to the “sign of the prophet Jonah”—in other words, to himself. Otherwise, his signs were “all about new creation: water into wine, healings, food for the hungry, sight for the blind, life for the dead.”

So Jesus is “standing at a moment of great transition.” Like one of the prophets of old he calls Israel to repent and get off a road that will lead to a catastrophic war against Rome. But at the same time, he points forward to a new world, in which he himself will be the one true sign, and—seemingly—it will no longer be possible or necessary or right to read the signs and ask what we should be repenting of. Jesus says, “Don’t be disturbed; the end is not yet” (Matt. 24:6).

Surely not! The saying belongs to the narrative of the build up to the catastrophic war against Rome. The end is not yet: there will be war, hunger, earthquakes; the community of disciples will come under intense strain because of their witness to the coming reign of Christ; the good news of what YHWH is doing in Israel will be proclaimed to the nations… and then the end will come! There is no comfort for us in this. It’s all of a piece. Indeed, this is exactly the point that Wright makes in Jesus and the Victory of God (346-48).

In much the same fashion, he takes the Lord’s prayer out of its historical context, arguing that he expected them to pray it every day, “not just when a sudden global crisis occurs.” I think Jesus taught them to pray in this way precisely because Israel faced a national crisis. He took his own immediate historical circumstances much more seriously than Wright—of all people!—seems to think. The prayer is that God would act decisively and soon to repair the damage done to his reputation in the ancient world by Israel’s shocking behaviour, and that the disciples would play their part in this “judgment” well.

Wright is so anxious to forestall the modern apocalypticists that he refuses to allow Jesus a positive apocalyptic vision of his own future. He argues that the New Testament focuses everything on the death and resurrection of Jesus and that we must simply work outwards from there.

But that’s not what Jesus did. Jesus’ vision was centred not on his death and resurrection but on the future judgment and vindication signified by the symbolism of a son of man figure coming on the clouds of heaven. His answer to Caiaphas was not that the Council would see him raised from the dead but that before this corrupt generation of Jews disappeared from history (Matt. 10:23; 16:28; 23:36; 24:34, and parallels), they would see him seated at the right hand of Power and coming with the clouds of heaven.

My point is that we cannot separate Jesus from the concrete moment and the looming historical crisis. If we are going to appeal to the Gospels to make sense of the pandemic, we cannot carelessly present Jesus as a universal abstraction—even representing the renewal of creation—and say that history doesn’t matter.

The famine in the days of Claudius

Wright’s ideal pattern for Christian behaviour is illustrated by the story of the response of the church in Antioch to the prospect of a great famine (Acts 11:27-30). They do not interpret it as a sign that the Lord is coming back. They do not use it as an opportunity to call people to repentance. They don’t start a blame game. “They ask three simple questions: Who is going to be at special risk when this happens? What can we do to help? And who shall we send?” This is what the church is all about. The Spirit was given to empower a diverse community of very ordinary people to go about the work of new creation.

That’s fine, but what prompted this pragmatism in the first place? Prophets came from Jerusalem to Antioch, and one of them, Agabus, predicted that there would be a severe famine across the whole oikoumenē. The natural disaster was not assimilated into any apocalyptic timeline, but God was involved because Agabus spoke “by the Spirit.”

What I think we should consider today is the possibility that interpretation of coronavirus as a warning of the much greater catastrophe of climate change and environmental collapse may likewise be inspired by the Spirit. It’s a wake-up call, a chance for the world to sober up and face reality. It’s not the second coming of Jesus, it’s not the end of the world, but it’s eschatology as it appears from our perspective, and it’s beginning to look like a rather grim “day of the Lord” for humanity. The sad thing is, the prophets are to be found among the scientists and activists, the politicians and even business leaders, not in the church.

Wright likes to say, as in this book, that “As Jesus was to Israel, so the Church is to the world.” I would qualify that: as Jesus was to Israel, so the early church was to the Greek-Roman oikoumenē (more on this in a moment), and now the modern church is to the whole planet.

Why should that not include prophecy? Jesus prophesied to Israel about the coming judgment and restoration. The early apostolic church prophesied to Rome about régime change. But the modern church has lost the nerve, it lacks the vision, wisdom, and language to prophecy meaningfully to the planet. Brueggemann, at least, I feel, moves us in that direction.

Paul’s preaching in Athens

Wright thinks that Paul’s preaching in Athens underlines the point that the message of the New Testament is all about Jesus and not about history. Paul “simply refers to the one great sign: God is calling all people everywhere to repent through the events concerning Jesus. Jesus himself is the One Great Sign.” The argument hinges, Wright says, “not on any independent events, not on some big crisis that’s just occurred, but on the facts concerning Jesus himself.”

He makes the same mistake here as he does with Jesus. Paul calls the men of Athens to repent of their idolatry because God’s patience has run out and he has “fixed a day on which he will judge the oikoumenē in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed” (Acts 17:30-31). In Luke’s writings the oikoumenē is the classical pagan sphere or the Greek-Roman world or the Roman empire (Lk. 2:1; 4:5; 21:26; Acts 17:6; 19:27; 24:5). It’s the region that suffered famine in the days of Claudius (Acts 11:28). This is not a judgment of all humanity. It is judgment of a section of humanity in history. Paul doesn’t even name Jesus at this point. He merely backs up his assertion that their world will be turned on its head by saying that God has raised this man from the dead.

We should also note here Paul’s summary of the faith of the Thessalonian believers, who did precisely what he would call the men of Athens to do: they abandoned their idols, turned to the living God, and waited for his Son from heaven who would deliver them from the judgment to come (1 Thess. 1:9-10). For these believers the real significance of Jesus lay ahead of them, not behind them.

The New Testament does not allow us to take Jesus out of history. He is inextricably part of an unfolding past, present and future.

Worthy is the Lamb (to open the scroll of judgment)

What about the book of Revelation? Again Wright goes out of his way to stifle the prophetic dimension. It is “full of fantastic imagery which is certainly not meant to be taken literally as a video-transcript of ‘what is going to happen.’” It’s just a rather elaborate way of “drawing out the significance of the primary revelation, which is of Jesus himself.” The suffering of the followers of the Lamb simply manifests to the world the suffering of Jesus himself.

This is sheer obfuscation. The whole point of the apocalyptic genre was to assure downtrodden communities that God would fix things in the not-too-distant future—judge wickedness in Israel, end oppression of the righteous, overthrow the pagan nations, and establish his own rule in the midst of them. The “revelation of Jesus Christ” is the revelation given to the exalted Jesus by God “to show to his servants the things that must soon take place”; it ends with the assurance that Jesus is “coming” soon (Rev. 1:1; 22:20). When he is revealed as the Lamb who was slain, it is because he must open the scroll that will unleash judgment, first on Israel, then on Rome. The whole thing climaxes in the fall of the great city which was corrupting the nations.

I understand the need to discourage modern apocalyptic fantasists, but the solution is not to pretend that John had no interest in future events. The solution is to recognise that his future was historical, just as our future is historical, and God is always the God of history.

The groaning of creation

This is the big New Testament theme in the book. In Romans 8 Paul describes the exodus journey that believers are on, led by the Spirit, towards their “inheritance”, which is the renewal of creation. But we cannot make this journey without sharing in the suffering of the Messiah, and when, as now, the world is going through convulsions, we must groan in the Spirit (Rom. 8:26). The followers of Jesus are called not to yell “you’re all sinners” from the sidelines, Wright says, or announce that “the End is near,” but to be “people of prayer at the place where the world is in pain” (italics removed).

This is not very different from Brueggemann’s reading of this passage. I think that both of these great scholars have missed the real point of Paul’s argument here, which is 1) that a particular community of witness is being conformed more or less literally to the pattern of Christ’s suffering and vindication; and 2) that the foreseen outcome is not the renewal of creation but the establishment of kingdom.

But Brueggemann at least keeps our real world in view. The virus is God’s way of telling us that the narratives of consumerism and globalism will fail because “such practices contradict the given reality of creation and the will of the creator.”

Being a people of prayer when the world is in pain is not wrong. But why is Wright so determined to have us locked down in our small rooms of lament? Why is he so reluctant to attribute to the living God any more dynamic emotion than grief, any more constructive intention than to remain silent? Humanity is approaching the greatest crisis in its history, with the possible exception of the flood, and we have a God who has nothing useful to say about it?

Dare we then say that God the creator, facing his world in melt-down, is himself in tears, even though he remains the God of ultimate Providence? That would be John’s answer, if the story of Jesus at Lazarus’s tomb is anything to go by. Might we then say that God the creator, whose Word brought all things into being and pronounced it ‘very good’, has no appropriate words to say to the misery when creation is out of joint? Paul’s answer, from this present passage, seems to point in that direction. The danger with speaking confident words into a world out of joint is that we fit the words to the distortion and so speak distorted words—all to protect a vision of a divinity who cannot be other than ‘in control’ all the time.

Isn’t this a false antithesis—between a divinity who must be in control all the time and a divinity who must remain speechless? Jesus didn’t just weep at the tomb of Lazarus. His intention was always to “awaken him” in order to make a point about resurrection and life (Jn. 11:11, 25). He was clearly “in control” of the situation. The apostles were groaning not because creation was out of joint but because their witness to the future rule of God’s messiah over the nations of the Greek-Roman world was so vehemently opposed by Jews and pagans. But they had no doubt that God was “in control” of this slow, long-term historical process (Rom. 8:31-39).

A narrative of accountability

We, as the church, do not have to single out any particular group for blame, though we might want to start by admitting our own complicity in the crisis. It is the whole global progressive-consumerist system that is at fault. We should not confuse it with the apocalyptic scenarios envisaged in scripture; if anything, it is far more serious. We should certainly lament, in the way that the prophets lamented, both before and after catastrophe. We should do all the good things that Wright urges us to do in chapter five, though I think he rather overestimates the relevance of the church in the modern world.

But the biblical witness encourages us explicitly to frame the lament and the prayer and the service in narrative-historical terms.

Jesus told Pilate that his authority was from God and that God would hold to account those who had handed him over to him (Jn. 19:11). Wright infers from this that “we need proper investigation and accountability for whatever it was that caused the virus to leak out, and for the lesser ways in which various countries and governments have, or have not, dealt wisely in preparing for a pandemic and then handling it when it rushed upon us.”

Very sensible and practical (now who’s the “cause-and-effect pragmatist”!), but myopic surely.

I think we must seriously consider the possibility that the virus is a warning that God will hold modern humanity accountable for its greed and folly.

The world is going through convulsions—environmental, economic, and social. The church is having to learn quickly how to speak on behalf of the living God with intelligence, discernment, clarity, and conviction.

As you are aware, I am a big fan of the hitorical-narrative approach and it has fundamentally altered my approach to scripture and theology in important ways. I think the modern evangelical chruch far too often makes everything abstract, psychological and theological rather than rooted in history and events.

And I have a sense that Wright is falling back into this trap having pushed the boundaries about as far as he felt he could. The new creation approach fits much better within the larger evanglical world. I am not assigning motives to Wright, this is just what it appears to me from the outside reading his writing.

But I have two issues with your approach to these books and to the issue of the pandemic and the ecological crisis.

One is that the evanglical church can’t suddenly switch gears to a prophetic historical-narrative approach to the pandemic when it hasn’t even really wrestled deeply with issues like the triumph of secularism/paganism, the growth of popularism/nationalism, and the challenge of consumerism and celebrity culture within and without the church. They are comfortable in their theologicalized and abstracted buble, happy to add a patina of new creation or mission or some other lable to freshen up their hermenutics. Prophetic voice is a step too far. Unless of course you are speaking out against things the dominat culture is already comfortable with castigating/pontificating about: implicit racism, global warming, corporate greed, elite priveledge, etc. Mostly progressive churches are cofmortable with low risk prophecy on these topics which rarely challenge their own members. A few brave souls have dared to speak out on uncomfortable issues for conservatives but it is more rare.

Which brings me to point two: I think there is a real risk in getting too far out on crisis and losing your credibility. And relatedly, I think exageration has already caused much damage in both the environmental and the pandemic cases.

Take this statement: “Humanity is approaching the greatest crisis in its history, with the possible exception of the flood.” I simply don’t beleive this is the case. At the every least, I would need to see a lot more evidence to believe it. My knowledge of history makes me sketical.

Without getting into a debate about global warming or an ecological crisis, and acknowedlging that plenty of people have their heads in the sand for ideological reasons, exageration and ideological fervor has undermined prudent policy and public understranding at nearly every turn. If the church gets caught up into hysteria reagarding current events it risks becoming even further marginalized or becoming part of a polarized politics. And their is a long history of cranks attempting to use current events to make theological points and coming out the worse; their are good AND bad reasons prophecy is associated with cranks and cults. And I thnk you can’t approach this issue without wrestling with this history and culture.

And I think this is a difficult time where political polarization threatens everything. I am conservative by temprement and political philosophy in many ways, but I think this is a danger for both sides. Just as I decry the evanglicals in America who have embraced nationalism and abadoned character in the age of Trump so to I decry progressives who seem to be all to willing to use Christianity as a weapon in the culture wars but in the name of domestic politics and environmentalism (which frequently seems a religion unto itself).

I think we know far too little about COVID-19 and surrounding issues to speak with clarity and foresight about the historical implications, let alone attempt to tie them into God’s judgement on the world. I think secularism, nationalism, and consumerism are plenty enough for the church to wrestle with and speak prophetically about without having to wade into the murky waters of the pandemic.

Thus are my thought from a small village in Ohio anyways…

Very provocative. Thanks. I will have a stab at addressing your concerns. But I am very conscious of the fact that the attempt to extend the narrative-historical trajectory into our own era is fraught with difficulty. I don’t mind taking the risk occasionally, but there’s a good chance I’ve misjudged the landing place.

My guess is that to some extent this reflects our different locations. I write from a British perspective, and while I doubt my point of view is representative of the majority, I don’t think that the church here is stuck at the same point of cultural change as the church in the US. Your first issue appears to be that the “prophetic historical-narrative approach” to the pandemic or anything else is ahead of its time, come back in fifty years.

I’m not sure how defensive to get about the second point. I could just say, well, let’s use this crisis as a test case for the methodology. Let’s pursue this as a thought experiment. How does it sound if we try to tell the story in this way? I would be quite comfortable with that, but I can’t help thinking that there really is something very serious that we—as church, as humanity—need to come to terms with, so for now I’m prepared to try a more stubborn defence.

If the church gets caught up into hysteria regarding current events it risks becoming even further marginalized or becoming part of a polarized politics.

That’s a somewhat loaded way of putting it. The climate debate is not just a clamour of hysterical voices. There’s a good deal of sanity going on behind the scenes as scientists do the painstaking work of gathering and interpreting the evidence, and I have to say that my comment about the “greatest crisis” since the flood does not seem to me particularly hyperbolic. There is good reason to think that we are facing global flooding, extreme weather conditions, desertification, drought, famine, mass migration, economic chaos, and massive loss of species. I can’t think of anything more severe in the postdiluvian era. Can you?

That aside, why should the church not look for a way of speaking about and for God that escapes the extremes of joining in the polarised hysteria, on the one hand, and retreating into a safe silence, on the other?

Is there really a good theological reason for thinking that the God of the scriptures no longer has anything significant to say about human history? Wright makes a lot of the fact that Jesus was the last person to be sent to the wretched vineyard of Israel; therefore there is no further need to speak on God’s behalf about historical events. But is that really persuasive? Jesus was decisive for the judgment and renewal of Israel and transformation of its place in the world, but does that answer every question? For a start, it wasn’t Jesus who saw that the solution to Israel’s problem would lead to the conversion of the Greek-Roman world. Others were sent to the nations with, actually, a quite different message. History proceeds.

And if I make the admittedly hazardous hermeneutical move of identifying the revelation of Jesus to the nations with the conversion of the Greek-Roman world, I am bound to ask about the theological or eschatological significance of the deconversion of the West, the dethronement of Jesus, over the last two or three hundred years. The possible collapse of global modernity would be just another momentous chapter in this long saga of YHWH and his people, and isn’t it our responsibility to tell that story well, to the glory of God, as difficult as that may appear to be? If not now, then later. If not in America, then somewhere else. But I don’t see how we can with integrity highlight the intensely difficult and demanding historical dimension to the New Testament texts without at the same time addressing our own place in history on the same terms.

I can well imagine that this seems a tall order from an American perspective because the church is so deeply entrenched in the culture wars, and clearly there is a lot of fighting still to be done. But here in the UK the problem is that the church has shrunk to the point of invisibility, and it may be that the challenge to speak about the creator God in the midst of a crisis of creation gives us a way to re-engage in the public arena without falling into the old cultural and political traps. Climate change, like coronavirus, transcends the rift between left and right.

I think we know far too little about COVID-19 and surrounding issues to speak with clarity and foresight about the historical implications, let alone attempt to tie them into God’s judgement on the world.

Of course, but the pandemic is an ecological issue one way or another. It may well have been a consequence of a bad relationship with the natural world, it is exceptional in its global reach, lockdown has opened the eyes of many people to the damaging impact of industry and travel, and I hear lots of people in Europe saying that we should rebuild a “greener” economy. It’s becoming a powerful secular argument to say that coronavirus is both a warning of worse to come and a spur to widespread social change.

To speak of God’s judgment on the world, finally, is obviously problematic, but you don’t need to be a person of faith to think that coronavirus and similar disasters are a direct consequence of bad human behaviour. A sort of quid pro quo. This needs more thought, clearly, but is it so unreasonable to say that the God of the whole world is disruptively redressing the balance because he is faithful to the promise made, in this case, to Noah that he would not again destroy all flesh? Why not tell such a big and relevant story about the God of history?

@Andrew Perriman:

Thanks for engaging with what I wrote. Nice to have civilized and intelligent discussion on the internet.

I will put aside the complicated issue of global climate because I think that is likely to take us too far afield. But the totalitarian forces of the last century were a bigger threat to humankind that global climate change in my opinion (the deaths that resulted from Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, etc. are staggering and too easily forgotten).

I don’t beleive that “coronavirus and similar disasters are a direct consequence of bad human behaviour” in a direct or global way. With the very large exception of China, which has played an outsized role in spreading misery and death across the globe and to millions of their own citizens. Perhaps that is an area where Christians could find a prophetic voice.

But one area where there could be much fruitful, even though uncomfortable, focus is this:

And if I make the admittedly hazardous hermeneutical move of identifying the revelation of Jesus to the nations with the conversion of the Greek-Roman world, I am bound to ask about the theological or eschatological significance of the deconversion of the West, the dethronement of Jesus, over the last two or three hundred years. The possible collapse of global modernity would be just another momentous chapter in this long saga of YHWH and his people, and isn’t it our responsibility to tell that story well, to the glory of God, as difficult as that may appear to be?

This is exactly what I think the churches of the West should be wrestling with and exploring but I think question about the story we tell and whether Jesus is still Lord of his church are better than God sent this pandemic because humans have acted badly.

For fundamentalist evanglicals, the temptation is to simply assum this is the end times (yet again) and try and save as many people as we can. For the left I feel like the equally easy fall back is progressive politics which neatly provide the answer to any crisis. Asking why the church has been pushed from the center of culture and what the church is called to in this emerging world should engender harder questions.

I agree that events like the pandemic and resulting lockdowns should act as opportunities to pause and rethink our assumptions and actions. The stay at home orders provide a good opportunity to think about consumerism and whether we are acting out of the search for comfort or the callings we have as the people of God. With churches shut down we can ask uncomfortable questions about their place in our neighborhoods and communities.

I guess what I am trying to get at is the difference between trying to understand what God might be calling us to in an age of pandemic and economic and ecological diaster and the assumption that God is punishing the earth for specific actions.

But I don’t have any good answers.

I’m not sure I have any good answers either, but here’s an attempt to address some of the points that you raise. Thanks for explaining your perspective.

Paul calls the men of Athens to repent of their idolatry because God’s patience has run out and he has “fixed a day on which he will judge the oikoumenē in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed” (Acts 17:30-31). In Luke’s writings the oikoumenē is the classical pagan sphere or the Greek-Roman world or the Roman empire (Lk. 2:1; 4:5; 21:26; Acts 17:6; 19:27; 24:5). It’s the region that suffered famine in the days of Claudius (Acts 11:28). This is not a judgment of all humanity. It is judgment of a section of humanity in history.

And in further support of this above point, it could be noted regarding the immediacy of such history… along with the oikoumenē of both Acts 11:28; 17:31 the word mellō meaning ‘about to’ is also used; being indicative of that which is on their immediate horizon — and thus not something delayed, postponed nor put out into some distant never-never eons.

Your thoughts on the virus, scripture and the challenges are thought provoking and stimulating.

You say:

“It is the whole global progressive-consumerist system that is at fault”

I agree with the sentiment. How is it connected with the corona virus epidemic?

@peter wilkinson:

In the first place, the link is symbolic. Just as the fall of the tower of Siloam was not directly linked to the future destruction of the city but was for Jesus a sign or symbol for it, so I think that we may “prophetically” treat the pandemic as a sign or symbol for the far more serious global crisis of a climate emergency.

The globally disruptive nature of the pandemic is a core aspect of the symbolic connection. Coronavirus is more like the foreseen climate emergency—in its impact on life, livelihood, and way of life—than any other natural event in the modern era. “The pandemic is a cataclysmic event so big and disruptive that it can be measured in the planetary metrics of climate change” (A Pandemic That Cleared Skies and Halted Cities Isn’t Slowing Global Warming).

There is the positive symbolic point that the pandemic has shown us something of the environmental benefits of reduced carbon emissions, noise, travel, consumption, etc.

Finally, there is the more direct scientific argument that viruses are making the jump from animals to humans because of the pressure that we are putting on the natural order—on the one hand, the intensive farming required by massive populations; on the other, widespread encroachment on the the natural environment.

- How will coronavirus shape our response to climate change?

- Climate change and coronavirus: Five charts about the biggest carbon crash

- ‘The parallels between coronavirus and climate crisis are obvious’

- How our responses to climate change and the coronavirus are linked

- Coronavirus is an SOS: Mend our broken relationship with nature, says UN and WHO

@Andrew Perriman:

Just a quick instinctive initial gut reaction response to a quick reading of your review. If I may sum up the difference in responses: Wright thinks we should get off our soapbox, lament, suffer with, and help the needy. You (along with Brueggeman) think its a prophetic opportunity. My reaction is, why be driven into an either/or response to this ? Don’t we need both? Perhaps if we did what Wright was saying to start with, people would be more ready to listen to the prophetic voice that came with the loving action. It may be Wright is reacting to those who stand on their soapboxes trumpeting judgment and do nothing to help the poor unfortunates who often end up suffering most in a corporate judgment.

@Andrew B:

Yes, a good point well made. But (I hope this doesn’t sound too defensive) my argument from the start was that, biblically speaking, lament and prophetic speech go hand in hand. Lament is not just an expression of sympathy with those who suffer. It is an acknowledgement of failure, at the level either of the individual or, more commonly, of the nation. Jeremiah lamented over the past destruction of Jerusalem, Jesus lamented over the coming destruction of Jerusalem.

So if we are going to invoke lament specifically as a biblical category, we have to very seriously the prophetic dimension. Part of what that means, I think, is exactly identifying with those who suffer, but in the way that the “prophet” Jesus identified with those who suffered—to bring into sharp focus the failings of the political-religious system and the coming intervention of God on behalf of the “poor” in Israel.

Identification and compassion are an important part of the validation of prophecy, but I would argue that where we really fall short is in telling a meaningful story about the God of history in this time.

@Andrew Perriman:

Fair enough. But then it may be a question of what we start with. Because of the unique set up of Israel which was founded on covenant commitment to Yahweh, prophets did not need to earn a hearing — they had a recognised right to speak out, as did Jesus coming into his own people Israel with its legacy of covenant, law and prophecy pointing towards him. The prophetical role was a recognised role; there was no argument about having divinely appointed prophets. The only argument was, who are the real prophets?

We are in a much more awkward position; we don’t have a legacy like that to appeal to, just a historical legacy of Christendom, with all the negative associations for which liberal enlightenment humanism finds itself reacting against (empire, hypocrisy, church-state collusion, religious wars, Christian monarchs with mistresses galore etc etc).. U.S christian politics plays into all that and gives us a very bad image indeed (Evangelicals supporting Trump, uncritical support for Israel etc). Christendom brought real blessings as well, which the humanists are all too slow to acknowledge, but on the other hand we have a lot to live down in terms of negative associations. Where Wright may be coming from is that we need to win the right to be heard before we get on the soapbox. I think because of that we may need to start with Wright and then we are in a better position to do Brueggeman. What do you think?

@Andrew B:

That’s very interesting.

I wonder if the status of Old Testament prophet was quite as secure as you suggest. Yes, there was a debate over who were the real prophets, but if a prophet was something of an outsider (Jeremiah?), he needed to gain a hearing and often failed to do so.

True, we don’t share a narrative with secular society, but then Jonah didn’t share a narrative with Ninevite society, Paul didn’t share a narrative with Athenian society. So they had to make one. Paul, according to Luke, framed pagan history within the story of the creator God (Acts 17:22-31). He devised a narrative, somewhat consistent with the Old Testament vision, that spoke of the decline of the pagan world and the arrival of a new “Christian” order, ruled over by the risen Lord Jesus.

So can we do something similar today?

It is hardly a Christian argument to say that human behaviour is leading to climate catastrophe. Most scientists are saying just that. My question would be, if that is the case, why the church is not able, or is so reluctant, to connect this massive global event with the God who made the heavens and the earth. Why shouldn’t we do what Paul did, so outrageously, when he manufacture a shared prophetic story for the Greek-Roman world, even if they didn’t get it at the time?

So the prophetic part is not to say that climate catastrophe is going to happen (if that’s what we think), but to say how the living God is in this crisis.

Yes, you’re quite right, we have a miserable legacy as the modern church—that is part of the story, needs to be confessed, and perhaps atoned for. But then Paul the Jewish apostle was also saddled with the dubious reputation of the Jews in the ancient world, who had brought the name of God into disrepute (Rom. 2:17-24). Paul was not a Christian who had left failed Judaism behind. He was a Jew who believed that God was doing something new to reform and reinvigorate his people.

@Andrew Perriman:

Yes, I agree, we are slow to engage with a prophetic perspective on climate change, which is a good place to start, because it is widely recognised as a corporate problem created by corporate sin (though the world does not like the sin word) . I think evangelists should be finding a way of bringing a prophetic perspective on climate change into their evangelism. But it’s more difficult than for Paul in Athens; at least his hearers did believe in a transcendent heavenly realm where gods acted on human affairs and where people sort out divine oracles. We, on the other hand, as Wright says, are living in a world where Epicureanism is the default mode for secular culture rather just than a niche market for a section of the leisured class.

Unfortunately our culture’s understanding of consequences is driven by a materialist perspective. Somehow we need to get over the OT Jewish perspective that God put the consequences there, is at work through them and, like the wise woman in Proverbs calling out in the streets, is trying to speak to us through them.

Corona is a more difficult one, because it cannot be straightforwardly seen as a problem created by all of us in the way that Climate Change can. We can tell ourselves that we don’t allow live animal markets of the kind that exist in China, so we see it as their fault and we are suffering. But we know that Climate change is our fault.

@Andrew B:

Corona is a more difficult one, because it cannot be straightforwardly seen as a problem created by all of us in the way that Climate Change can.

I think lot of people would see the pandemic as symptomatic of the stress to which humanity has subjected the planet—threatened natural habitats, the global travel industry, etc. I responded to a similar observation here.

Recent comments