My response to Peter Wilkinson’s attempt to show from Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus had no thought of reforming or restoring Israel as a nation has grown too long to post as a comment. My contention, more or less in agreement with Caird and Wright, is that the Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels announced a coming judgment on the state of Israel, largely because of the corruption and obduracy of the ruling elites, but he nevertheless expected the people of Israel to continue under a new covenant in fulfilment of Old Testament prophecies, with himself as its true king.

I would suggest, further, that Paul had not moved very far from this belief even at the time of the writing of Romans. God’s people were at heart reformed, new covenant Israel as heirs to the promises made to the patriarchs according to the flesh, but an increasing number of Gentiles were being added to this people, grafted in to the rich root of the patriarchs, on the basis of their belief that Jesus had been made Lord above all powers. This was not, alas, having the effect of making the Jews jealous, but Paul clung to the hope that after judgment his people would see the error of their ways and so repent and be saved. It didn’t work out that way, so we are now left with an overwhelmingly Gentile people of God drawing unnaturally on the promises made to Abraham.

But all that’s beside the point. Here I consider each of the passages in Matthew that Peter cites in support of his view, and several that he doesn’t.

Matthew 1:21: The angel tells Joseph to call the boy Jesus because “he will save his people from their sins”.

Matthew 1:22-23 The Immanuel prophecy in Isaiah has reference to the presence of God with his people to judge and redeem them.

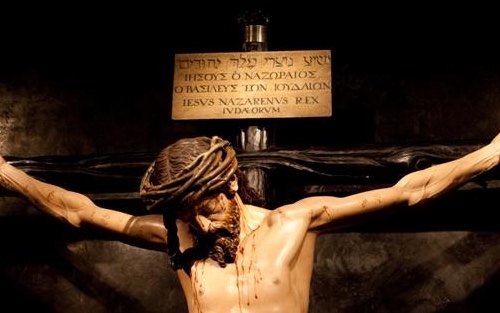

Matthew 2:1-6 The birth narratives make much of the fact that Jesus would be “king of the Jews”, “a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel”. The trajectory of the infancy stories is firmly in the direction of the redemption of sinful Israel and the establishment of Jesus as king. This theme runs all the way through the crucifixion. It makes no sense to present Jesus as the Davidic king who would rule over his people for ever if Israel as a people was to be terminated.

Matthew 3:16-17 Jesus is identified at his baptism as the anointed servant, the true Jacob, obedient Israel, which would bring justice to the nations (Is. 42:1-9).

Matthew 3:10 John the Baptist speaks of “trees” plural, allowing for a differentiation within Israel. “Every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.” Trees that do bear good fruit (all the righteous and the repentant sinners in the Gospels) will not be cut down.

Matthew 3:12 The metaphor of the threshing floor entails the separation of the righteous from the unrighteous. Only the unrighteous are destroyed. Part of Israel will survive as Israel. Nothing in the imagery suggests that the wheat becomes something completely different.

Matthew 4:1-11 The testing in the wilderness identifies Jesus as obedient Israel.

Matthew 4:12-16 Jesus’ ministry begins with the quotation of Isaiah 9:1-2, which is a prophecy not of judgment and termination but of restoration.

Matthew 5:17 “I have not come to abolish the Law and the Prophets” means that Jesus has not come to abolish the Law and the prophets. He must fulfil the Law and the Prophets without abolishing them or negating their relevance for Israel as Law and Prophets.

Matthew 7:13-14, 24-27 Jesus says that most Jews are going through a wide gate leading to destruction but some will find a narrow path leading to life. The two ways image is used in the Old Testament to describe the choice between life and death put before Israel (cf. Deut. 30:15; Jer. 21:8). The parable of the two houses serves a similar purpose.

Matthew 8:11-12 It’s quite possible that Matthew intended the faith of the centurion to anticipate the later faith of Gentiles in the authority of Jesus as Lord, but this does not mean that Jesus thought that national Israel would be excluded from the kingdom. If it is correct to think that Jesus is referring to Gentiles rather than to scattered (cf. Is. 43:5; Zech. 8:7) or unprivileged Jews, the most we can say is that they will be included in the eschatological celebration of the reformation of Israel. The “saved” will recline at table with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—this is not Paul’s theology of inclusion in the promise to Abraham by faith. The “state” of Israel will fail, but Israel will survive without a state, as it did during the exile.

Matthew 9:16-17 The sayings about the cloth and wineskins relate to fasting, not to “the old nation of Israel”. “Two little parables pick up the theme of a new and joyful pattern of religion which is incompatible with the old traditions represented by the fasting regimes of the Pharisees and the followers of John” (France). Of course, if we take the saying out of context, we can make it mean whatever we like.

Matthew 11:20 That the cities of Israel face catastrophic judgment is not in dispute. The issue is whether Jesus thought that “Israel” as a people would survive. I think it is pretty clear that Jesus expected a righteous, repentant remnant to be justified, to become a new community of Israel, living according to a Law written on their hearts by the Spirit in a new covenant, recognising the exalted Jesus as its king.

Matthew 12:39, 46-50 Jesus condemns the scribes and Pharisees as an “evil and adulterous generation”, but at the same time he says of his disciples, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:49–50). This is said to Jews about Jews. There is no basis for the assertion that Jesus is dissociating himself from “racial ties”—the distinction is between the religious elites and the ordinary people who gather to hear Jesus. The same thought is found in Matthew 7:21: “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.”

Matthew 13:1-30, 36-43 The parables of the sower and the weeds all have to do with division within Israel between those who respond positively to Jesus’ message and those who do not, between the righteous and the unrighteous. Israel will be judged, but the wheat of Israel—the righteous—will be preserved. The imagery does not allow for the destruction of all Israel and the beginning of something completely new.

Matthew 15:21-28 The faith of the Canaanite woman is a rebuke to faithless Israel. But the healing of her daughter is incidental. Matthew does not suggest that the encounter changes Jesus’ mission “to the lost sheep of the house of Israel”. This saying evokes the narrative of Ezekiel 34:1-24: Jesus is the “one shepherd, my servant David”, who is set over the sheep who have been maltreated by the corrupt leadership of Israel. Jesus’ purpose is to recover, restore and govern the lost sheep of Israel as their true Davidic king.

Matthew 16:4 The “evil and adulterous generation” sayings are always directed at the scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees. This does not mean that there will not be repentant and righteous Jews who will survive the destruction as Jews to be the nucleus of a renewed Israel. Yes, the failed “state” of Israel and its institutions faced destruction—especially the temple. But everything that Jesus says and does assumes the continuation of something from within Israel as a sufficient expression of a new covenant people. He fulfils the Law and the Prophets by judging and restoring Jacob.

Matthew 17:17 The whole point of the story of the healing of the epileptic boy is the exhortation to the disciples to have faith: “For truly, I say to you, if you have faith like a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you” (Matt. 17:20). Whatever precisely that means, it is clear that Jesus expected part of Israel to demonstrate a viable faith and therefore not be included in the “faithless and twisted generation”.

Matthew 20:20-28 The little exchange between Jesus and the mother of the sons of Zebedee tells us only that those who will reign in the coming kingdom of God will gain that authority because 1) they have suffered (“Are you able to drink the cup that I am to drink?”), and 2) they have not acted autocratically in the manner of the Gentiles. Authority in the kingdom will come by following the path of the suffering Son of Man. The passage certainly cannot be used as evidence that Jesus expected something other than Israel to continue.

On the contrary, the twelve disciples (signifying the beginning of a restored family of Jacob—not of Abraham) would be ruling over Israel: “Truly, I say to you, in the restoration (palingenesian), when the Son of Man will sit on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Matt. 19:28, modified translation). Josephus uses palingenesia for the “restoration” of the homeland (patris) following the exile (Jos. Ant. 11.66).

Matthew 21:12-13 The destruction of the temple did not mean the destruction of Israel as a nation, only as a state. The people of Israel survived the destruction of the temple by the Babylonians—they just needed to find a new modus vivendi. Jesus evokes precisely this narrative when he quotes Jeremiah in the temple: “Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your eyes?” (Jer. 7:11). It will become a “house of prayer for all peoples” when God restores Israel following judgment. Presumably Jesus believed that he himself would be the new temple, but this cannot be understood apart from the Old Testament narrative of the judgment and restoration of the people of Israel.

Matthew 21:18-19 The withering of the fig tree is usually understood as an acted parable for the coming judgment. The curse seems pretty final: “May no fruit ever come from you again!” In context, the fig tree may represent the temple in particular rather than Israel itself, which is why there is no conflict with the numerous other parables and sayings which point to the continued existence of a renewed people. “The withering of the fig tree is thus an apocalyptic word of judgment… that will find its analogue in the future destruction of Jerusalem and its temple” (Hagner).

But this is not obviously the meaning that is attributed to the miracle. Jesus approached the tree because he was hungry, and he makes the miracle an example of what the disciples will be able to do if they have faith and do not doubt. Perhaps Micah’s lament is more appropriate, in which case the cursing of the fig tree would represent Jesus’ anger over injustice in Israel:

Woe is me! For I have become as when the summer fruit has been gathered, as when the grapes have been gleaned: there is no cluster to eat, no first-ripe fig that my soul desires. The godly has perished from the land, and there is no one upright among men; they all lie in wait for blood, and each hunts the other with a net. (Mic. 7:1–2, modified)

Matthew 21:43-44 In the parable the vineyard planted by the master is presumably Israel, the people (cf. Is. 5:1-7); the wicked tenants are the corrupt leadership of Israel: “The identification of the tenants as the current Jerusalem leadership is demanded both by the context in which this parable is set (as still part of Jesus’ response to the chief priests and elders, which began in v. 27) and by the explicit comment in v. 45” (France). The old leadership of Israel will be replaced by a new leadership. France again is worth quoting:

The term ethnos, “nation,” … takes us beyond a change of leadership to a reconstitution of the people of God whom the current leaders have represented. But on the other hand the singular ethnos does not carry the specific connotations of its articular plural, ta ethnē, “the Gentiles.” We may rightly conclude from 8:11–12 that this new “nation” will contain many Gentiles, but we saw also at that point that this is not to the exclusion of Jews as such but only of those whose lack of faith has debarred them from the kingdom of heaven. The vineyard, which is Israel, is not itself destroyed, but rather given a new lease of life, embodied now in a new “nation.”

France also suggests that there may be a deliberate echo of Daniel 7:27: “And the kingdom and the dominion and the greatness of the kingdoms under the whole heaven shall be given to the people of the saints of the Most High” (Dan. 7:27). If this is correct, it is the suffering righteous, the community of the Son of Man, who will inherit the governance of the restored people of Israel—that is, the disciples who will sit on thrones judging Israel (Matt. 19:28; 20:20-28).

Matthew 23-24 Jesus prophesies judgment on the current evil generation, which will come in the form of war against Rome and the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. But in this judgment the humble will be exalted (Matt. 23:12)—those Jews defined by the beatitudes, the tax collectors and prostitutes who repented, the lepers and demoniacs who were healed, the disciples who take up their own cross and learn to lead by serving, and so on. Again, everything points not to the absolute termination of Israel but to its continued existence under radically new conditions. In the judgment Israel will be turned upside down—the mighty will be thrown down, the lowly and meek, the poor, those who mourn, will be raised up. But it will still be Israel.

Despite what you say, and the ingenuity of some of the comments (eg on the cursing of the fig-tree), there are no explicit statements cited anywhere that Israel would survive and continue as restored Israel. There is no argument about whether Jews would comprise the renewed people of God — they did, and initially 100%. But this did not constitute Israel. There is nothing to affirm that God’s plan was to preserve Israel, and plenty to affirm the opposite. Caird does not present detailed evidence for his view — only a rather sketchily drawn framework which does not reflect the thrust of Jesus’ teaching or actions. Some of my citations could be questioned; the accumulated evidence can’t. Jesus did not come to restore anything like national Israel; he never said he did; Paul never said he did, or that this was what was happening in the church. Missionary activity started almost immediately, and certainly when the Jerusalem persecution began. The ‘ripple’ effect of mission is then part of the structure of Acts — Jerusalem, Judaea, Samaria, the ends of the earth. Churches were planted in Antioch, Rome and elsewhere which included gentiles long before Paul got there.

Caird is right on ‘national eschatology’, but wrong on a political motivation to Jesus’ mission, and so are you. Israel, a people of God identified by their OT antecedents, was coming to an end, as far as Jesus and the NT were concerned. The big issue was what was being brought to birth by Israel’s end. Paul reinterpreted the OT in this light, a reinterpretation made necessary by the death and resurrection of Jesus. Ironically, I think you would be the first to disapprove of how Paul plays fast and loose (to us moderns) with the OT scriptures he cites to support his case. (Rather like Jesus, in fact).

Andrew & Peter,

I’m trying to figure out exactly the meaning behind the terms being used here and whether or not you guys are talking past one another. When referring to Israel (post AD70) continuing on under her new covenant, do you (Andrew) mean as an entity/body/people of YHWH, or Israel as a physical nation/state with physical borders etc.?

@Rich:

It can seem that way, but I think there’s a real difference. Clearly the church was formed partly of Jews who escaped judgment and partly of Gentiles. Peter appears to be arguing that this Jewish-Gentile body constituted a clean break from national Israel, which was fully destroyed in the judgment of AD 70. In retrospect that is a reasonable conclusion to reach. My view, is that everything that Jesus said and did presupposed the continued existence of Israel through a faithful remnant. So what would come after the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple was Israel reformed and restored.

The Gospel story is naturally told as part of the story of Israel—the historical context and the careful reliance on the Jewish scriptures means, as I see it, that the burden of proof lies very heavily on those who would argue that Jesus himself expected Israel to end and something new to begin. There are clear statements to the effect that Jesus would save his people, that Jeremiah’s new covenant with Israel would replace the old covenant, that the disciples would sit on twelve thrones judging Israel, and so on. There is nothing comparable to the effect that the Jewish people would cease and a new hybrid community would take its place.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

I’m in complete agreement with you. The OT prophets were clear that 1) YHWH would establish a new covenant with Israel - Jer. 31:31 for example and 2) YHWH would resurrect Israel — Ezk. 37 for example. See also 1 Cor. 15. Israel is the corporate “body” that was being raised.

Israel’s AD 70 event was the antitype of her 40 year wandering in the desert. The unfaithful were judged and a remnant would pass through entering the promise land maintaining the existence of Israel. Just as a remnant came out of the desert, so a remnant came out the other side of the AD 70 event maintaining the existence of Israel. The Church is Israel (Gal. 6:16), it just has Gentiles grafted into it — something must be there to be grafted into (Romans 11:17-18). Sure the number of Gentiles that responded were much greater than the number of Jews who remained faithful (it was a narrow path after all and only a few found it — Matthew 7:14), but it’s clear that some did — either a literal 144,000 or whatever number was symbolized by that number.

Anyway, thanks for the clarification. I’m won’t pile on to Peter. You two can hack it out.

-Rich

Are we talking past each other? I don’t think so, as Andrew’s argument on Israel is part of a broader package of radical continuity from the OT, in which Israel continues (until the end of so-called Christendom) to exercise a largely political role. I think Jesus radically redefined ‘kingdom’ to create discontinuity from its OT sense (in which judgment and violence were prominent features), and radical continuity which extends from his redefinition of the term to today.

Perhaps another question to answer is this. AD 40 and beyond did not eliminate the Jews or Judaism. Why then have Jews not taken for themselves the word Israel? Their survival, largely ignored in these discussions, surely gives them more right than Christians to the term. Isn’t the obvious answer the one that applies also for Christians: The word refers only to Jews in their own land living with all the panoply of OT theocracy. The word and its significance belongs to them, and they have rightly seen that it no longer applies.

@peter wilkinson:

Peter,

in which Israel continues (until the end of so-called Christendom) to exercise a largely political role

if that is a correct assessment of Andrew’s position then I disagree. I hold that Israel continued on as a people of YHWH post AD 70 via the remnant (believing Jews) who were baptized pre-AD70 into the body of Christ. This body (along with some Gentiles) became the Church. Thus, the Church is Israel. First they were The Way. That didn’t seem to stick. Then they were called Christians. That name seemed to stick, and that’s what we have today. Just because a new title seemed to stick to that group of people doesn’t mean they were no longer Israel. Titles change. Take the term Jew. Only those of the tribe of Judah are really Jews yet it came to be used in reference to any Israelite no matter what tribe he/she came from.

Why then have Jews not taken for themselves the word Israel? Their survival, largely ignored in these discussions, surely gives them more right than Christians to the term

How do you figure they have more of a right then the faithful Jews who were believers pre-AD70 and were “saved” making it through the Judgement? They were the fulfillment of what YHWH promised via all the OT prophets and Jesus himself. Why do those who rejected YHWH’s Christ even to this day get to claim the term Israel for themselves?

@Rich:

Rich — the church isn’t Israel for all the reasons given. It is not described as Israel in the NT. Your comments about Jews need some unpicking. Were Jews who made it through AD 70 also saved (since they survived, just as Christian believers did)? Since they survived, and continue to this day, why should they not call themselves Israel, with more justification than a largely gentile (today) church? The answer points to the reason why Christians do not and should not call themselves Israel, now or then.

@peter wilkinson:

Peter,

you haven’t provide any reasons. Paul in Gal. 6:16 does refer to the Church as Israel.

Andrew above has provided so much proof above I find it hard to take you serious on this matter. So, I’ll let you have the last word.

Blessings.

@Rich:

If I understand Peter’s point correctly in his last comment, I think it’s valid and not easily dismissed. More unbelieving Jews survived AD70 than believing Jews, so it’s hard for me to see how you can say the remnant were the “saved” Jews, i.e. the Church.

@peter wilkinson:

It seems to me that the confusion can largely be attributed to the fact that we are looking at this from at least three different perspectives.

1. The post considered only Jesus’ point of view. It seems to me incontrovertible that he simply thought in terms of the continuation of the reformed people of Jacob, constituted of the sort of Jews defined in the Beatitudes, perhaps with some Gentiles incorporated, under a new covenant and under a new régime, in accordance with Old Testament hopes for the restoration of Israel following a “final” judgment. We should not impose later perspectives, including Paul’s, on the Gospel narrative.

2. If Paul wrote Ephesians, then he appears to have thought that Gentiles were being included in the “commonwealth of Israel” (politeias tou Israēl), though perhaps this meant that the churches were in the process becoming something new as the “household of God, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone” (Eph. 2:19–20). Also I think that Romans 11:13-27 shows that Paul hoped that all Israel would repent after the catastrophe of AD 70, but he wasn’t to know how things would turn out. So the inclusion of Gentiles has at least opened up the possibility of discontinuity.

3. This brings us to the third perspective, which is the historical one. On the one hand, Peter points out that more unbelieving Jews survived AD 70 than believing. I’m not sure this is quite relevant as they did not survive as a new covenant people in the Spirit confessing Jesus as Lord. But still it reflects a historical perspective. On the other hand, we know as a matter of historical fact that the Church became an exclusively Gentile institution, with very little sense of its continuity with Israel, and is only now beginning to recover a sense of its relation to the Old Testament narrative, thanks to good old-fashioned historical-critical research.

@Andrew Perriman:

Jesus never uses the word “Israel” as in a renewed Israel, new Israel, or the survival of Israel (rather the opposite of the last). There is no confusion. He was clear on the issue. So is the rest of the NT, in which there is no mention of a continuing Israel at all. If there is a verse anywhere which refers to the continuation of national Israel, could you point me to it?

I think your hesitation about enlisting Ephesians to support Gentile inclusion in a new Israel is well founded. The Gentiles were at one time excluded from “the commonwealth”, πολιτεία, “of Israel,” — 2:12, but are now “fellow citizens”, συµπολιταί, not with Israel, but with “the saints and the household of God” … “on the foundation of the apostles and prophets” … “Jesus Christ himself being the cornerstone” — 2:19-20. Israel isn’t mentioned in this new people.

Romans 11:13-27 may reflect Paul’s hope that at some stage in the future Israel as a whole would repent, and possibly after AD 70 (though that is speculative). To me, a much more secure interpretation follows from the preceding chapters, in which Paul accepts (through great anguish) that only a remnant has repented, and on this basis there could (and will) be further repentance, but not a mass national repentance. This is because Romans 11:25-26 (and 11:11, 14) describes a continuing process.

Rather than saying that at some time in the future Israel as a whole will repent, Romans 11:11-26 is saying that during the period in which Gentiles are turning to God (11:25), there has been, and is, a partial (not complete) hardening of Israel (11:25b), during which time “all Israel” will be saved (11:26). Paul has been describing the very way in which Israel will be saved as a process, not an event.

“And so” (11:26), καί οϋτωϛ, means “And in this way”, which 11:11, 14 particularly describe as a process, in which “some” of Israel will be saved (11:14), which eventually will lead to “all Israel” being saved (11:26). “All Israel” can have the OT sense of a significant portion standing for the whole, or the grammatical sense of “all Israel who are going to be saved”, (or both meanings).

This of course does not chime with the narrative historical interpretation which you are proposing, but to me it makes sense not only of Paul, but connects our experience with his. It also frees us from the unlikely possiblity that Paul strongly believed that at some point there would be a national repentance of Israel en masse, which would have to be before Israel ceased to exist (ie as a nation), so by AD 135 at the latest.

Historical grammatical research is an important tool of interpretation, but it is only one of a number of tools which can and should be used. However, it is rarely an interpretive principle used by Jesus in his interpretation of the OT, and still less used by Paul. An example of Paul’s creative and non historical gramatical use of OT interpretation is in Romans 11:26, where he changes “The deliverer will come to Zion” (quoting Isaiah 59:20) to “The deliverer will come from Zion”, presumably to fit with the idea that Jesus was the deliverer of Isaiah’s prophecy, and also that the the mission of Gentile deliverance was and is, in the first place, a Jewish mission, and was taking place at that very moment through the likes of Paul himself.

Other examples of Paul’s creative and non historical grammatical use of OT interpretation are throughout Romans — sometimes taking verses and making them mean the very opposite of their OT historical gramatical sense. It’s odd that interpreters have kept quiet about this.

@Andrew Perriman:

I tend to agree with your first point, but as Peter said, it seems speculative in your second point that Paul was referring to a post-judgment repentance. I suppose you could argue Paul was a realist and knew this level of repentance couldn’t happen in the short time before Christ’s return, but I’m not convinced Paul thought unbelieving Jews would survive the soon-coming judgment.

I think the third point, the historical perspective, is valuable in assessing and interpreting Jesus’ and Paul’s views.

@Peter:

The argument about a post-judgment repentance is partly one of historical plausibility. It was clear to Paul that the inclusion of Gentiles was not provoking sufficient jealousy for Israel to repent as a nation. Paul expected Israel to suffer catastrophic judgment. 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch show that the Jews could interpret AD 70 as judgment and express repentance after the event. So it seems historically plausible to think that Paul imagined that his people would repent after the catastrophe. Historically speaking, there is no reason to think that he would have expected the Jews as a people to be utterly wiped out by the war.

But I think that the quotation of Isaiah 59:20 points to this sequence: God comes to punish Israel, Israel repents after punishment, Israel is restored.

@Andrew Perriman:

I did mention that Isaiah 59:20 as altered by Paul says that a the deliverer will come “from” Zion, not “to” Zion, as Isaiah has it, which doesn’t suggest a judge who comes to punish. It suggests to me a Jewish mission, which in the light of Romans 11 is to the Gentiles, and embodied in Paul himself. Further creative textual interpretation by Paul, of a non historical grammatical nature. (I haven’t heard from Tom Wright yet — interpret that however you like!).

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

We should not impose later perspectives, including Paul’s, on the Gospel narrative.

I don’t see how you can say such statements. You act as if God is not working through this unfolding story. As if Jesus and Paul were on their own with no “inside information”, if you will, to all the facts of what was unfolding.

Jesus obviously, being who he was, had been working out this story from the beginning (Genesis 1:1). Don’t think we need to question his knowledge and/or understanding of what was being accomplished via the Father, the Holy Spirit and himself.

Paul, while being just a man, was equally informed. First he was educated in the OT having studied it his entire life (Acts 22:3; Philippians 3:5-6), then on top of that God revealed to him, via revelation, the truth of the Gospel (Gal. 1:11-12). I would say Paul understood quite well what God had been doing from day one and how it was all being fulfilled in his day (1 Cor. 10:11).

As far as Jesus knowing/teaching that Gentiles were going to be brought into Israel, I think he made several statements that address that topic.

First, John the Baptist in Matthew 3:9 alluded to God being able to raise up children of Abraham even though they were not physical descendants.

Jesus, for example and one passage that pops off the top of my head and in-line with John the Baptist, pointed out that in the Resurrection the children of Israel would neither marry nor be given in marriage (Matthew 22:30). His point was Israel/children of Abraham would no longer consist of mere physical lineage, (Paul picks up this in Romans), which prior was the case and the reason why a brother was to take his dead brother’s wife as his wife to raise up offspring (Matthew 22:24).

Just because God changed, if you will, who/what constituted Israel (moved from physical lineage to those of faith) doesn’t mean it isn’t Israel. God made a promise. And because of that promise he would save OT Israel (Romans 9:3-5). But, not all were children of Abraham just because they were a physical descendant (Romans 9:7). Only those Jews of faith would be children of the promise (Romans 9:8) and there would only be a remnant (Romans 9:27), which means a small group, just as Isaiah stated. And on top of that Gentiles would be grafted in as well and also become children of Abraham (Romans 9:24-25) just as God stated in Hosea.

To argue that unbelieving Jews of physical descent (no matter what their number might be) also are Israel tells me that one has completely missed the entire message from the OT prophets all the way through the NT writings. I don’t know how Paul (especially in Romans) could have been any clearer as he made his arguments backed up by the prophets.

-Rich

@Andrew Perriman:

I keep getting hung up on personal salvation. After so many years of being taught this, it’s hard for me to consider anything else when I read the NT. :)

@Peter:

But there are passages like Acts 3:23 that do seem to say only Jews who repented would survive the coming judgment…

Let’s assume, for a moment, that Jesus in Matthew Gospel saw himself as the true and future king of Israel. This might have been credible in the first century, but subsequent history shows a different story:

- Christians have shamed the God of Israel by painting him as locked in unforgiveness from the fall of Adam to the death of Jesus. Such a doctrine, even in its mitigated forms, has always stood in contradiction to the lavish experience of forgiveness described in both the Hebrew Scriptures and in the parables of Jesus. Christians have, accordingly, proclaimed a false and misleading god to the Jews, and the Jews were right to reject it entirely. Since this falsehood is so intimately associated with Jesus, it remains unclear whether God could appoint Jesus as the moshiach of Israel in the end times without giving a false witness to an abhorrent misrepresentation of God.

- According to Matthew Gospel, Jesus anticipated that his disciples would some day “sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Matt 19:27f). How could the disciples of Jesus be expected to properly judge or guide Israel if they have been poisoned by a doctrine that “salvation is only found in the name of Jesus” and that “salvation consists in applying to Jews the merits Jesus earned dying on the cross”? One could assume, of course, that the Twelve would openly challenge such false doctrines. In so doing, however, the Twelve would be setting themselves up against the long-standing beliefs of Christians and, accordingly, risk being rejected as “true disciples of Jesus.” Given this terrible ambiguity, it remains unclear whether God would grant the Twelve any significant role when it comes to Israel in the world to come.

- The Church must also struggle with Elie Wiesel’s charge that “any messiah in whose name men are tortured is a false messiah.”[i] Thus, in humility and in truth, Christians must wonder whether the long history of Christian harassment, intimidation, and torture of Jews does not entirely preclude God from giving Jesus any significant role in the future of Israel. One can speak glibly of Jesus as being Jewish and sinless and the Son of God; however, this does not remove the fact that the name of Jesus has been historically tainted by the pain and horror of millions of Jews tormented in the name of this Jesus. Wiesel recounts his own story:

As a child I was afraid of the church . . . not only because of what I inherited‑-our collective memory‑-but also because of the simple fact that twice a year, at Easter and Christmas, Jewish school children would be beaten up by their Christian neighbors. A symbol of compassion and love to Christians, the cross has become an instrument of torment and terror to be used against the Jews.[ii]

Just as it is impossible to contemplate that God would use former S.S. officers to keep order during the final judgment, so too, it remains unclear whether the God of Israel could be so crass and insensitive as to allow the Crucified Savior to be the final judge of Israel.

So, with you, I ask, “Is this the kind of message that Christians really need or want to be proclaiming in favor of Jesus?”

Your brother, Aaron,

[i]. Elie Wiesel, The Oath (New York: Random House, 1973) 138.

[ii]. Elie Wiesel, “Art and Culture after the Holocaust,” Auschwitz‑-Beginning of a New Era? Ed.Eva Fleischner (New York: KTAV, 1977) 406.

@Aaron Milavec:

Aaron, thank you for your comments and for the very different perspective that you bring. I’ll do my best to respond briefly from my particular point of view.

1. It seems to me that judgment and forgiveness go hand in hand throughout the Bible. There are episodes of catastrophic judgment and there are moments of lavish and unmerited forgiveness. The theme of forgiveness in the prophets cannot be separated from the disasters of invasion and destruction by foreign powers. Even in the parables there is the real threat of judgment against, for example, the wicked tenants in the vineyard. We cannot sidestep this; it was Israel’s historical reality. But the assurance all the way through is that God will remain faithful to the people whom he has chosen to serve him.

2. It seems pretty clear, to my “Christian” eyes at least, that Jesus believed that only the way of faithful suffering that he opened up—as a Jew loyal to YHWH—would save his people from destruction. Israel was building its house on the sand, and within a generation a storm and a flood would wash that house away. The apostles in Jerusalem were likewise convinced, on the strength of the resurrection appearances, that YHWH had made the Son whom he had sent to Israel “Lord and Christ,” the only one by whom Israel would be saved from the coming catastrophe of the war against Rome (Act 2:36; 4:12). But I think that this can be construed quite pragmatically, much as Jeremiah presented the people of Jerusalem with “a way of life and a way of death.”

3. I think that in New Testament terms we can say only that God gave Jesus a say in the future of Israel in the short to medium term—through the judgment of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple to the point when it became clear (late first century?) that the Jews as a people were not going to change their minds about Jesus. After that, the church must be accountable for its treatment of the Jews.

Hi Andrew, I am wondering what your thoughts are on the modern nation of Israel and how Christians should think about them and Messianic Jews as well as Orthodox Jews and the issues surrounding conflict with surrounding nations? Got any posts on it? It seems to me that, at the most (regarding land), according to a narrative-historical reading of the Hebrew scriptures that Jews/Judahites would have claim to the land assigned to the tribe of Judah.

@Mathetes:

I’m not sure a narrative-historical hermeneutic gives much guidance on the question of Israel’s right to the land. As far as scripture is concerned, I think that modern Israel is off the map, far beyond the purview of Old Testament or New Testament prophecy. In the 50s Paul still held out hope that “all Israel” would repent and be saved in a foreseeable future, either before or in the aftermath of the judgment that was coming on his people, but that hope was not to be realised.

The logic of the rule of Israel’s messiah over the nations of the Greek-Roman world from heaven made the land and temple unnecessary, and in the post-christendom context, presumably, we think in terms of the global presence of the scattered people of God. If we want to ascribe significance to the land again, from a Christian point of view, it would be as a theological novelty.

I can’t say I’ve given a lot of thought to this, and there may be a better way of looking at the problem, even within a narrative-historical paradigm. Here are a few other posts that touch on the issue:

A very interesting discussion to me. Going outside of Matthew, to Mark, we have the parable of the wicked vinedressers in Mark 12 1-11. This seems quite conclusive. He will give the vineyard to others. He Himself has become the chief cornerstone, (though of course He always was). It therefore carries on through Jesus as Messiah, at once head of the true Israel, Jew and Gentile making up the church.

Recent comments