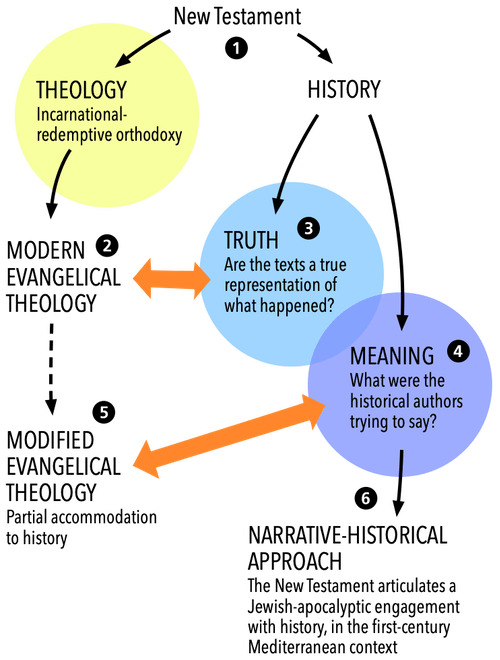

It’s summer in the northern hemisphere, and there’s not much happening, so I was doodling and came up with a little diagram to show the difference between traditional evangelical thought and the approach that I take on this blog. For many readers it will be familiar, but if you’re new here, it may blow your mind. Or maybe not.

1. Broadly speaking, there are two ways of reading the New Testament. We can read it theologically, or we can read it historically. The theological approach has dominated the history of interpretation and remains vigorous today—notably in the form of the Theological Interpretation of Scripture (TIS). The historical approach only really got going in the 18th century with the work of rationalist critics such as Reimarus.

2. The dominant theological tradition has read the New Testament according to an incarnational-redemptive paradigm or rule of faith. Its main purpose has been to proclaim, explain, and defend the central proposition that God entered the world as man to save sinners. Interpretation of the New Testament was subordinated to this task. Modern evangelical theology is defined, in the first place, by its relation to this historic (as opposed to historical) paradigm.

3. The modern historical method began as a re-evaluation of the tradition on the assumption that the truthfulness—or otherwise—of the New Testament witness is to be determined not by ecclesial authority but by critical enquiry. The New Testament was subjected to the acid rain of a zealous anti-religious scepticism, leaving it shredded and lifeless.

Scholarship came to the conclusion that the documents could not be trusted as a source of information about events associated with the supposed figure of Jesus—basically, the church had made the whole thing up, there was very little worth keeping. It is this reductionism, largely, that has provoked the distrust of historical methods that lies behind the Theological Interpretation of Scripture.

So modern conservative evangelical theology is defined both by its loyalty to the tradition and its opposition to destructive rational enquiry.

4. There is, however, a different type of historical question to ask about the New Testament texts. Not: is the New Testament true? But: what does the New Testament mean? What were Jesus and his followers trying to say? This is a much more constructive question. We still find ourselves at odds with the theological method but in a different way.

To cut a long story short, I think that the universal incarnational-redemptive paradigm is displaced by a Jewish exaltation-kingdom paradigm: the story of how God resolved the “political-religious” crisis faced by his people in the early first-century, and how through that resolution he established direct rule over the nations of the Greek-Roman world, through the Son whom he had raised to his right hand.

5. Evangelical thought has taken on board elements of the history-as-meaning model. We now hear more about the Jewishness of Jesus, the latent anti-imperialism of Paul’s gospel, and the overarching redemptive story that runs from creation to new creation.

But this is really only a selective accommodation of history to the powerful and complacent modernism that controls evangelical thought. It can hardly be regarded as a serious attempt to read empathetically from within the trenches of first-century Jewish thought, with all the constraints of practical concern and prophetic vision which that entails.

6. The “narrative-historical” approach that I argue for here is an uncomfortably rigorous attempt to discover and articulate this perspective. It cannot be done apart from more traditional historical-critical concerns, but its “truthfulness” is found not in any particular claims made by the text but in the more or less indisputable fact that a Jewish-Christian community in the first century told this story about itself. The other challenge is to show that an uncomfortably rigorous historical reading of the New Testament still has relevance for the church today. To my mind, the narrative-historical method is inherently evangelical.

Thanks for this, Andrew. A question perhaps for a future post: who else do you consider to be working in a narrative-historical space or on a related trajectory? I’m not interested in the full cast list, more just those who you personally consider yourself to be learning/working from/with.

And a related question: how did you get to where you’ve got to? I read your Romans book a few years ago and have been following along here since. As well as being an area of inquiry, your narrative-historical approach has something of a conceptual leap to it — it is a way of seeing. I’d like to hear a bit about that: was there a breakthrough moment for you, or did it evolve more gradually, or…? Were you pushed or pulled? Etc (Maybe I’ll get the picture if I read your other books)

@Arthur Davis:

A nice comment, Arthur. Thank you. I might come back to it, but a few quick thoughts for now.

As a broad generalisation I would say that most of critical New Testament scholarship since E.P. Sanders has been operating in a “narrative-historical space.” It’s simply been a matter shifting the focus from “How does the New Testament support traditional dogma?” to “How do we best make sense of the New Testament witness according to its full literary-historical context?” In this post I suggested that the method goes back to Albert Schweitzer. Most people who have come to it in the last twenty years will have been greatly influenced by N.T. Wright.

At the conservative/evangelical end of the spectrum, I think much of the interpretation is compromised by a reluctance to let go of traditional formulations and priorities.

At the historical-critical end of the spectrum, analysis tends to disintegrate into sociological description because there is no real interest in making scholarship work for the believing church. It’s regarded as a powerful political-religious story, but basically Jesus and his followers got it wrong. Paul Fredriksen is a good example of this.

So the challenge is to reconstruct a narrative that is more or less true to the historical perspective of the texts and which has genuine “evangelical” power, which has the capacity to inspire and form a people in service of the living God.

It is in these two respects that I find myself somewhat isolated: 1) I go further than most in confining the New Testament witness to Christ to the historical outlook of the first century; and 2) I resist the pressure to make the New Testament directly applicable as a supra-historical sacred text.

I struggle to think of many scholars with the same agenda, but there are certainly people in the vicinity—Matthew Bates’ Salvation by Allegiance Alone and Stephen Burnhope’s Atonement and the New Perspective come to mind. But there are plenty more, and it might be a good idea to do a bit of cataloguing some time.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew

Thanks for you post.

My question is in response to your following statement:

At the conservative/evangelical end of the spectrum, I think much of the interpretation is compromised by a reluctance to let go of traditional formulations and priorities.

Can conservative evangelicals let go of traditional formulations and priorities without rethinking the nature of what the Scriptures are? For example, you spoke that “a Jewish-Christian community in the first century told this story about itself.” But here you are speaking of the Scriptures as witness, perhaps along the lines of Walter Brueggemann. But in my conservative circles, the Scriptures are still understood to be the Word of God, that is verbal, plenary inspiration. This Summer’s edition of Cedarville magazine (a decent size liberal art’s university in Ohio) opens with a letter from the school president lauding the school for not compromising in its commitment to the ‘inerrancy, infallibility, sufficiency and authority of Scripture.’

Such a view, I think, lends itself to seeking a fixed body of knowledge from which we can be confident in how we are to live. Further, I think that it tends to down play the real differences between the varied times in which the Scriptures were written and the time and varied places in which we live today.

I do not see how we can completely embrace ourselves as being a real part of the ongoing story of God unless we are willing to see the Scriptures themselves as witness (rather than fact).

Any thoughts? Am I barking up the wrong tree?

@Jason Brubaker:

You’re barking up the right tree, Jason, and you make the point very well. But I think things will change.

On the one hand, there is a vibrant dialogue under way amongst scholars and others around the world about the historical Jesus and the mission of his followers. I get only limited opportunities to teach on these things in the UK and Europe, but I find that there is a growing openness to thinking differently, even at a grassroots level and in quite conservative church and mission contexts. I am optimistic.

On the other hand, I think that the bastions of the verbal-inerrancy model will dwindle over the next few decades. I can’t see them surviving, even in the US, except in a very sectarian mode of religious life that will largely be ignored.

Having said that, I’m not sure it’s inerrancy that’s the real issue. You could have a pretty good narrative-historical take on the Bible and still insist that texts are directly inspired by God and in all respects accurate. That’s difference between history-as-truth and history-as-meaning But the conservative church has used the rigorous hermeneutic to defend a narrow, reductionist and flawed definition of “the gospel.” Question the incarnational-redemptive paradigm and you are denying the truth of the Word of God.

Thanks for another helpful post, Andrew.

Question: it seems inevitable to me that if the approach to the Scriptures that you advocate is widely embraced within the churches, it will raise the question: “what sorts of stories should we be telling now about ourselves, the people of God, and the Creator?”

That’s not a particularly scary question to me (post-evangelical but still sympathetic to the people and, consequently, sensitive to things that are of deep concern to that movement), but the next one is a bit more so: “How should churches in the future regard the stories that we tell now?” Should we expect that some of these stories should or will come to be regarded to have the kind of authority that is currently ascribed to the old stories?

Fourth question, if I may: “Do we need prophets, again?”

Not trying to be “difficult”. I’m genuinely curious about this. Things need to change, and I’m wondering about the longer-term ramifications.

@Samuel Conner:

Should we expect that some of these stories should or will come to be regarded to have the kind of authority that is currently ascribed to the old stories?

You could compare modern storytelling to the construction of patristic orthodoxy, which I would regard as itself a continuation—and misrepresentation—of the New Testament narrative under different conditions. Theological orthodoxy has had a massive authority in the church, and we struggle still to work out how to balance it against the independent authority of scripture.

I would argue that the orthodox paradigm is in decline, and we may indeed find that we are implicitly generating a new story (or theology) for the post-Christendom age comparable in force to orthodoxy. But it will still have to be, I think, an interpretation of the Bible, and to that extent, at least, we will give priority to scripture.

Fourth question, if I may: “Do we need prophets, again?”

I don’t think our epistemology, our intellectual culture, really allows us to have old style biblical prophets, except perhaps in limited and isolated instances. But I certainly would argue that the church in the West needs a shared, intelligent, biblically grounded, imaginative, Spirit-led prophetic vision—to account for the crisis that we are confronted with, and to give expression to a new viable future for a people devoted to the service of the living God under the lordship of his Son.

Recent comments