This article questions the theological weight of Paul’s portrayal of creation as a suffering thing in Romans 8:19-22 and its ability to support a prophetic response to ecological issues. The author argues that the standard interpretation of creation’s suffering as a result of Adam and Eve’s sin is over-ambitious and suggests a more limited historical account of creation’s subjection to Greek idolatry. The article also critiques the focus on Rome as the cause of ecological devastation, arguing that Paul’s argument is about Greek idolatry, not environmentalism or anti-imperialism.

In our age of intense ecological anxiety, Paul’s sympathetic portrayal of creation as a suffering thing, yearning for liberation from its bondage to corruption (Rom. 8:19-22) has an obvious appeal. It’s a remarkable image, but how much modern theological weight can it bear? Can it support the sort of heavy-duty prophetic response that I think is needed to undergird the mission of the church in the western context, if not globally, as we enter the Anthropocene?

The statement looks both forwards and backwards—forwards to the revelation of the sons of God and the liberation of creation from the slavery of corruption, backwards to a moment when creation was subjected to futility.

The standard understanding is that all created existence is included in this span. Dunn writes, for example: “What is at stake in all this is creation as a whole and the fulfillment of God’s original intention in creating the cosmos.”1 The cause of creation’s suffering is found in the original sin of Adam and Eve, which resulted in the entry of death into the world (cf. Rom. 5:12), pain in childbirth, and the cursing of the ground (Gen. 3:16-19). The future consummation is the end of all things and the beginning of a new creation (cf. Rev. 21:1-8).

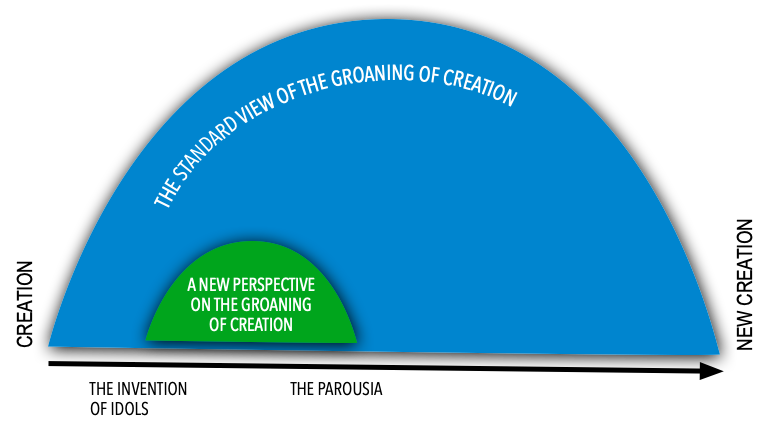

I suggested in The Future of the People of God: Reading Romans Before and After Western Christendom that there are two stages to the future fulfilment envisaged here: the vindication of the sons of God at the parousia, at the time of the confession of Jesus as Lord by the peoples of the Greek-Roman world, and then much later the final renewal of creation. The point was that creation looked forward to the first event as a sign and guarantee of its own eventual liberation from suffering. Now I think that there may be a better way of construing the relation between the two trajectories.

The standard interpretation is theologically useful because it encompasses the whole of human experience. My argument here will be that, as with much theological interpretation of scripture, it is over-ambitious. What Paul puts forward is not a universal but a limited historical account of the subjection of creation to the futility of “Greek” idolatry, consistent both with his critique of Greek idolatry in Romans 1:18-32 and with the speech that Luke gives him to make in Athens (Acts 17:22-31).

The scholarly obsession with Rome

That Paul might be thinking here in contingent political-religious terms was suggested by two speakers on the Ecological Hermeneutics / Paul and Politics stream of the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting.

First, Crystal Hall argued that Paul’s language echoes not the primal fall of humanity but the subsequent descent into violence portrayed in Genesis 4: the blood of Abel cries from the earth, Cain is cursed from the earth, which has opened its mouth to receive his brother’s blood, and there will “be groaning (stenōn) and trembling on the earth” (Gen. 4:10-14 LXX). Cain then goes off and builds a city, which is the prototype for Babel, which is the prototype for Babylon, which is the prototype for Rome.

Secondly, Robert Mason proposed to make use of post-colonial interpretive strategies in order to imagine how the provincial non-elites, among whom Paul elucidated his gospel, might have perceived Rome’s ideologically determined abuse of the environment. In particular, he suggested that the unnamed agent of creation’s subjection in Romans 8:20 is not God or Satan (the usual suspects) but Caesar.

I think that these two scholars are right to break with the standard theological interpretation, but in focusing on the ecological devastation inflicted by Rome on subjugated territories they mistake the target of Paul’s analysis. Paul is neither an anti-imperialist nor an environmentalist. His argument about the groaning of creation is an argument about Greek idolatry.

Let me explain.

Wrath against the Greek

Paul’s critique of idolatry in Romans 1:18-32 is grounded, I think, not in Genesis 2-3 but in a distinctly Hellenistic-Jewish analysis of the origins of the dominant Greek culture. The Greeks should have perceived the transcendent reality of the creator God in the natural order but instead made for themselves images of created things to worship. This is quite different to the sin of Adam and Eve.

So God handed them over to uncleanness and unnatural sexual practices, and to all manner of unrighteousness. The prominence given to same-sex relationships in this passage, therefore, is attributable not to Paul’s fundamental anthropology but to a civilisational analysis. For the details and the implications for our own telling of the “evangelical” story see my book End of Story? Same-Sex Relationships and the Narratives of Evangelical Mission.

The same contingency is operative in Paul’s address to the “men of Athens” in Acts 17:22-31. Despite the proliferation of objects of worship—so distressing to a devout Jew such as Paul (Acts 17:16)—the Greeks have overlooked the God who made the world and everything in it, who is not “like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man” (Acts 17:29). God has long turned a blind eye to this ignorance, but he has now fixed a day when he will judge the Greek-Roman oikoumenē “in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed” (Acts 17:30-31).

So I suggest that in Romans we are dealing with a limited historical outlook: the period of classical pagan hegemony, which would end with wrath against the idolatrous practices of the Greeks.

Now to the argument about creation in Romans 8.

The sufferings of the now time

Those who will be heirs-together (synklēronomoi) with Christ, Paul writes, are those who suffer-together (sympaschomen) in order that they may be glorified-together (syndoxasthōmen) (Rom. 8:17). Again, contrary to the theological consensus, I have to insist that he is not talking about the experience of all Christians throughout history. It is the exclusive community of the persecuted witnesses to the coming reign of Christ over the nations that will share in his inheritance and glory.

The “sufferings of the now time” (Rom. 8:18) are the afflictions experienced by the apostles and by the churches at this particular eschatological moment—the birth pains of the age to come. The afflictions are real but trivial by comparison with the glory that will be revealed to them when Christ is accepted as Lord and King by the nations of the Greek-Roman world. They are now disgraced, humiliated, and harassed, but eventually they will be vindicated for their faith, found to have been right all along, and thenceforward held in high esteem.

Creation also looks forward to this climactic moment in history.

At some point in the past, creation “was subjected to the futility (tēi… mataiotēti… hypetagē), not willingly, but because of the one who subjected it in hope.” It therefore “groans together and suffers-pain together until the now” (Rom. 8:20, my translation). But when the sufferings of the persecuted apostles and churches come to an end, creation will be “liberated from the slavery of corruption (phthoras) to the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21-22).

Two texts help us understand how Paul came to this conclusion, drawn from works that unquestionably influenced his thought in Romans. The first is Isaiah 24, the second is Wisdom of Solomon 14.

The Lord is ruining the world

Isaiah 24 is an oracle of judgment, probably against the “land” of Israel and its environs rather than against the whole “earth,” but that doesn’t make too much difference here.

- The people who live in the land, from the greatest to the least, from the priest to the slave, have “transgressed the law and changed the ordinances—an everlasting covenant” (Is. 24:5 LXX). The nature of the sin strongly suggests that the passage principally has Israel in view.

- Because of this, “the Lord corrupts (kataphtheirei) the inhabited world (oikoumenē) and will make it desolate” (Is. 24:1 LXX). The land will be “corrupted with corruption” (phthorai phtharēsetai) and “plundered with plunder” (Is. 24:3 LXX). A “curse will devour” the land (Is. 24:6 LXX). This is a change that has taken place in history, not at the beginning of history: there used to be natural and social flourishing; now the vineyards are wasted, streets are silent, cities are desolate (Is. 24:7-13 LXX).

- Therefore, the land “mourned” (epenthēsen), and the vine “mourns” (penthēsei) (Is. 24:4, 7 LXX). The land grieves over the wickedness that has been committed on it and over its entanglement in the fate of the people.

- In fact, the experience of the land mirrors the experience of its inhabitants: the land mourned and the “exalted ones of the land mourned”; the land behaved lawlessly (ēnomēsen) because its inhabitants transgressed the Law; the vine will mourn, and “all who rejoice in their soul will groan (stenaxousin)” (Is. 24:7 LXX).

- The oracle concludes with the affirmation that in the end the Lord will punish both the hosts of heaven and the kings of the land. He will reign in Zion, “and before the elders he will be glorified” (Is. 24:21-23).

If Isaiah 24 is an oracle about the “land,” then its scope is narrower than Paul’s appropriation of the prophetic argument in Romans 8:19-22. But the basic shape of the argument is the same: divine action by which the land is subjected to corruption (phthora); the mourning or groaning of the land; the parallel between the experience of the land and the people who live on it, though Paul’s interest is in the hope of the righteous rather than the lawlessness of the unrighteous; and a final scenario in which the Lord reigns and is glorified among the elders of Judah, just as the “sons of God” will be glorified in the presence of Christ.

But we also need to account for the widening of Paul’s perspective.

Idolatry and the corruption of life

His argument about the “degeneration” of Greek civilisation in Romans 1:18-32 echoes several themes in the standard Hellenistic-Jewish critique of pagan religion.

The author of Sibylline Oracles Book 3, for example, says that idolatry was introduced into the world 1500 years back by the Greek kings, which led to vain thinking (ta mataia phronein). But the wrath of God will come upon them, and they will “groan (stenaxousai) mightily and stretch out their hands straight to broad heaven and begin to call on the great king as protector and seek who will be a deliverer from great wrath” (Sib. Or. 3:551–561).

Similarly, we read in Wisdom of Solomon of the impending “visitation” of divine judgment on the idols of the nations. The idols as physical objects are “part of the divine creation” (en kismati theou), but their invention was “the beginning of fornication, and the discovery of them the corruption (phthora) of life” (Wis. 14:11–12). The created order has been misappropriated by the pagan nations, and the result is corruption.

The end of creation’s enslavement to the corruption of idolatry

Paul clearly draws on this analysis, or something very much like it, in the first two chapters of Romans—indeed, in one of the SBL sessions Margaret Mitchell accused him of having plagiarised Wisdom of Solomon. The wrath of God has been—and will be—revealed against the Greek world because they did not acknowledge the transcendent power of the living creator God, but “became vain” (emataiōthēsan) in their thinking and “worshipped and served the creature rather than the creator” (Rom. 1:18-23, 25; 2:9-10).

If we suppose that Paul still has this polemic in mind when he gets to chapter 8, there is good reason to connect the argument about the subjection of creation to the futility and its enslavement to corruption with the widely referenced Jewish narrative of Greek idolatry and an impending divine judgment. The article with “futility” (tēi… mataiotēti) may, in fact, look back to the whole argument about futility in Romans 1:21.

The general subjection of creation to futility or vanity, in that case, is a consequence of the fact that the physical materials of God’s creation have been forced into the service of pagan religion. Gold, silver, and stone (cf. Acts 17:29) do not want to serve idolatry; they have been conscripted against their will (hekousa). Because idolatry leads to the “corruption of life,” this is a “bondage to corruption” (tēs douleias tēs phthoras).

Perhaps the subjugation was God’s doing, in much the same way that God “handed over” the idolatrous Greeks to dishonourable passions and a debased mind (Rom. 1:24, 26, 28). But if we allow for a simple parenthesis in the text, the one subjecting creation to futility could easily be the “Greek”:

For the eager expectation of the creation awaits the revelation of the sons of God (for the creation was subjected to the futility, not willingly, but because of the one having subjected it) in the hope that the creation itself will be liberated from the slavery of corruption to the freedom of the glory of the children of God. (Rom. 1:20-21, my translation)

So within the purview of Paul’s apostolic mission, the foundational “error” (cf. Rom. 1:27) of the Greeks in manufacturing and worshipping images has resulted in the subjection of creation to the futile practice of idolatry; it has been forced into servitude to a religious system that corrupts life in the manner described in Romans 1:24-31.

This is why creation is so eager to see the revealing of the sons of God on the day of Christ. When, because of Jesus, the nations of the oikoumenē abandon their idols en masse and finally worship the “immortal God,” creation will no longer be subjected to the pointless production of “images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things,” and will be liberated to be what the creator always intended it to be—a sign of, or evidence for, “his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature” (Rom. 1:20-23).

The future fulfilment means not only the establishment of Christ’s rule over the nations and the vindication of his followers, but also the end of Greek idolatry and with that the liberation of creation from its implication in the corrupting practice of idol worship.

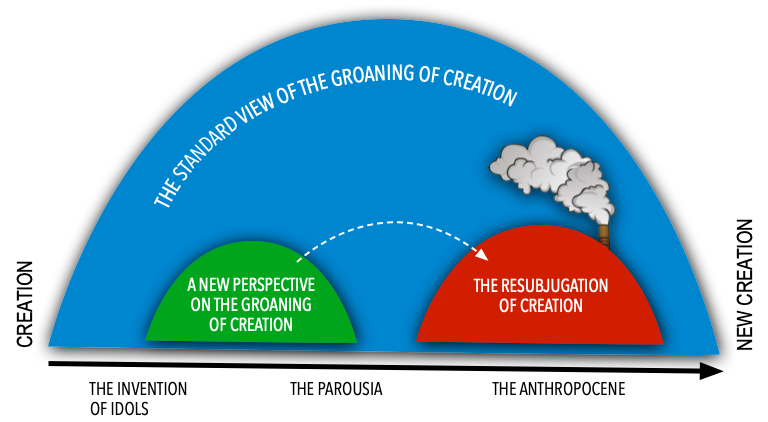

The re-enslavement of creation in the modern world

So the passage is less useful to the modern post-colonial, eco-prophetic programme than we might have hoped. It has its own historical context, and I think that it makes excellent sense in that context. So I have moved this passage to the second horizon category in my table of eschatological texts, leaving only 1 Corinthians 15:24-28 and Revelation 20:7-21:8 as third horizon texts. That will be disappointing to some people.

It was reported a couple of days back, however, that scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Sciences in Rehovot, Israel, have worked out that by the end of the year the weight of human-made products on the earth will exceed the weight of living things. Christmas will no doubt be the straw the breaks the camel’s back. That’s ironic—the celebration of the birth of Israel’s impoverished king.

If creation was liberated from its servitude to Greek idolatry when the nations of the Greek-Roman world confessed Jesus as Lord, over the last couple of hundred years it has been resubjugated, compelled against its will to feed the monstrous appetite of modern, global consumerist society.

Only it may not merely groan with those prophetic communities that desire a better world. It may be getting ready to fight back.

- 1J.D.G. Dunn, Romans 1–8 (1988), 487.

Wow. You nailed it again. Now it is getting much more concistency than traditionally. Well done. That changes all biblical arguments used today for the better and helps construct more plausibility of theological argumentation. I love it.

@Helge Seekamp:

Now, I worked it through and produced a sermon in three parts (GERMAN Language).

Thank you again for the exegesis and your approach, Andrew!

My latest attempt in St. Pauli Lemgo:

I am putting my congregation through the catastrophe. I have overcome my fear.

An German Pastor, Peter Aschoff, quote:

“There is Team Rainbow (Eden Culture) in the church and Team Apocalypse…” (Bendell apocalyptic with Perriman-supported realistic hope).

Video from www.st-pauli-lemgo.de

Part 1: https://youtu.be/JA8unU0vfKg

Part 2: https://youtu.be/JA8unU0vfKg

Part 3: https://youtu.be/pfd8H2uFnVg (coming soon)

Here the transcription as TEXT in GERMAN.

Very nice, Andrew; thank you!

A (perhaps bone-headed) question: given the immediate proximity of the following ch 9, would it be valid to see an element of “first horizon” also in view? Pretty clearly Paul’s anxieties about the fate of his countrymen are related to his sense of impending “first horizon” events, and at the time of Paul’s writing, the churches in aggregate are still mostly Jewish and the worst persecutions are happening “Jew on Jew” (which Paul would be quite familiar with, have previously been one of the persecutors). Perhaps the first person pronouns in ch 8:31-39 are self-referential or primarily “believing Jew”-referential, and this text is counterpoint to contemplation of the “first horizon” wrath that is in view starting with 9:1.

I’m trying to see less discontinuity between the end of ch 8 and the beginning of ch 9 than is commonly reckoned. If the ch 8 liberation from bondage and the glorification of the sons of God is entirely 2nd horizon, it remains a bit jarring that there is this sudden shift to first horizon concerns in the space of a single verse.

@Samuel Conner:

That’s a very interesting suggestion. It would mean reading Romans 8:19-22 as more like Isaiah 24 and less like Wisdom 14, and we would have to weaken the link with the argument about creation and creatures in Romans 1:19-25. But I wonder if Paul would have thought about a liberation of the land of Israel from its bondage to decay. He doesn’t mention the land in Romans 9:4-5.

There is perhaps a better way of explaining the abrupt shift of focus at the beginning of chapter 9. The argument to this point has been, among other things, that the descendants of Abraham will inherit the post-pagan world (cf. Rom. 4:13) not on the basis of adherence to the Law but on the basis of enduring faith in the future reality of Christ’s rule over the nations of the empire (cf. Rom. 15:12).

In Romans 8:18-39 Paul restates the conviction in somewhat unusual terms: through the faithful witness of the apostles and churches, creation, which has been forced to serve the practice of idolatry, will be liberated from that futility, because the nations will abandon their idols.

But this “glory”—this stunning accomplishment—should have been Israel’s. After all, “to them belong the adoption, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship, and the promises” (Rom. 9:4). It should have happened either because Israel as a people kept the commandments (traditional Jewish eschatology) or, when that failed and God had to come up with a different strategy, a different way to hold the world accountable (Rom. 3:6, 19, 21-22), because Israel as a people confessed Jesus as Lord.

So he turns to talk about Israel, which faces that first horizon of God’s judgment (cf. Rom. 9:22), because it should have been his own people according to the flesh who got the credit for bringing the long hegemony of classical Greek-Roman paganism to an end. Instead, it was the Gentile church that triumphed.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thank you, Andrew; this is helpful and I agree it does a better job than my hypothetical.

If I may be suffered to pick at this scab a bit more, though…

I notice a possible connection between some of Jesus’ warnings (false Messiahs, false prophets) and the 2nd big revolt, 132-135. From my reading of Josephus’ account of the AD66-73 war, there does not seem to have been a strong religious component to the motivations of the rebel leaders. Florus’ (seemingly intentional — that’s how JF portrays it, IIRC) maladministration pushed the people beyond their limit of endurance. The rebel fighters in besieged Jerusalem seem to have been interested more in exploitation of the civilian population than in redeeming Israel from pagan overlordship. There was little diaspora participation (for unknown reasons; I like to hypothesize that the memory of the suppression of a popular messianic movement 40 years prior was sufficiently fresh that many Jews in both “the land” and the overseas communities were still cautious; doubtless there are other and better explanations)

132-135, OTOH, does seem to have a strong religious component — there is an identified (false) messiah, and the religious establishment is behind the revolt. Perhaps R. Akibah could be regarded to be an example of a contemporary false prophet. Believing Jews in the land, remembering Jesus’ warnings and rejecting the latest false messiah, did not participate in the revolt and for that reason were subjected to severe persecution. The aftermath of deportation of the population and erasure of the name “Judea” seems to me reminiscent of the Leviticus 18 warnings about the land vomiting out its inhabitants should they “defile” it.

(I’ll note parenthetically that the Lev 18 transgressions that result in defilement of the land and ultimately exile are sexual in nature, which seems somewhat parallel to Paul’s focus on the corruption of Gentile practices in Romans 1; I have no information about whether this was actually a concrete issue in 2nd century Judea)

It also reminds me a bit of Mt 25 in the sense that the people who perished in the conflict were the same kinds of people, and doubtless often the same individuals, who afflicted the non-militant Jewish Jesus-followers.

Should the “first horizon” be broadened a bit? Paul’s Romans 10 assurance (directed, I think, primarily toward Jews) that “salvation” lies along the path of acknowledging Jesus as lord (both verbally and in the sense of believing that he was vindicated by God from the charge of ‘false messiahship’ by being raised from the dead) remains relevant to the Jewish churches for decades after AD73.

@Samuel Conner:

I can’t comment on Josephus in detail off the top of my head. There were certainly plenty of false or failed messiah-type figures in the period before and during the war (cf. Acts 5:36; 21:38). And the war started with a revolt against Rome over taxation, and other issues, and a successful assault on the garrison.

But the other question is what belongs to foresight and what to hindsight. With hindsight we can perhaps see how later details could be aligned with details in the teaching of Jesus or Paul, but we also have to ask what constituted realistic foresight on their part.

It seems like too much of a stretch to tie Paul’s statement in this eighth chapter to his earlier statements about Greek idolatry. I think the traditional view makes more sense—Paul was thinking about God cursing the ground in Genesis; however, it’s possible he was referring to events in Isaiah.

Either way, his point remains: groaning by men, creation, even the Spirit will cease when Christ returns, so his listeners must patiently and faithfully wait.

@Peter:

It seems like too much of a stretch to tie Paul’s statement in this eighth chapter to his earlier statements about Greek idolatry.

Is it really such a problem to suppose that the letter draws on certain consistent underlying themes, motifs, ideas? The analysis of Greek religion stands prominently at the head of the letter. Is it so unlikely that the creation subjected to futility in chapter 8 is the creation misused by futile minds in chapter 1?

There is another point of contact that I think adds weight to my argument. Creation shares in the hope in which “we were saved” (Rom. 8:24). The salvation hope in Romans is quite sharply defined. For the Greek, it is salvation from the wrath that was coming on the pagan world because of idolatry (Rom. 1:16-23; cf. Acts 17:30-31; 1 Thess. 1:9-10), and it is a hope in the future rule of Jesus over the nations (Rom. 15:12-13).

So precisely according to the terms of Paul’s gospel, creation’s hope is directed towards a moment when idolatry will be abolished and Jesus will rule over the nations of the Greek-Roman world at the right hand of the living creator God.

@Andrew Perriman:

I certainly think Paul could have chosen to use a consistent motif like idolatry, but I don’t see that here. Since chapter 8 is a continuation of 7, we can safely say Paul is speaking to Jewish believers here; therefore, I think it makes much more sense to connect creation’s groaning with God’s curse on the land that came about because of Adam’s sin. It seems Paul is contrasting the beginning with the end.

While the book of Romans addresses the hopes of both Jewish and Gentile believers, I don’t think you will find the ramifications of Greek idolatry mentioned in these chapters.

@Peter:

Since chapter 8 is a continuation of 7, we can safely say Paul is speaking to Jewish believers here; therefore, I think it makes much more sense to connect creation’s groaning with God’s curse on the land that came about because of Adam’s sin.

But then it was my point that the issue at the heart of Romans is whether and how God’s people (at this stage still in principle Israel) would inherit the post-pagan world, the nations of the empire. This is not just a peculiar concern of Paul’s. It is present in the prophets and in extra-biblical Jewish texts. I would say that the whole argument directed at the Jews in Romans (I agree with you about the centrality of this theme) is about why, as things stand, the Jews will not inherit, and how the God of Israel has put forward an alternative strategy.

@Andrew Perriman:

Wouldn’t you agree that Paul believed most Jews would inherit the world? He said they stumbled but they didn’t fall, and even though some branches were broken off, Paul still held out hope that they would be grafted back in, which is why he refers to Jews’ “full inclusion” in Romans 11:12.

I guess I don’t see this as an alternative strategy … maybe a shifted timeline? Instead of Gentiles turning to Yahweh after the kingdom of God is established, Yahweh starts bringing them in earlier to motivate Jews through jealousy.

@Peter:

Paul still held out hope that they would be grafted back in…

Paul may have had the hope that apostate Israel would repent, and be grafted back in, and therefore inherit the former pagan nations under the rule of Christ. But my view is that we have to keep in mind that he was writing a decade before the outbreak of war in Judea. He was beginning to doubt that his people would repent before the wrath of God came upon Israel, but perhaps they would repent after the catastrophe.

What would he have concluded if he had lived long enough to see his people persevere in their rebellious mindset through to the Bar Kokhba revolt 60 years later? We don’t know, but I imagine he would have found it all very depressing

@Andrew Perriman:

Yes, I think if Paul had known that most Jews would never come around to accepting Jesus as the Messiah, and if he had known how Gentiles would transform “The Way” into a new non-Jewish religion, he would have been quite depressed.

His argument about the “degeneration” of Greek civilisation in Romans 1:18-32 echoes several themes in the standard Hellenistic-Jewish critique of pagan religion.

(I’ll note parenthetically that the Lev 18 transgressions that result in defilement of the land and ultimately exile are sexual in nature, which seems somewhat parallel to Paul’s focus on the corruption of Gentile practices in Romans 1;…

Andrew and Samuel, hi…

To my mind… given Israel’s history of wanton idolatry, e.g., the golden calf incident et al, I’m inclined to think based on Rom 1:18-19, 21, 32 that Paul’s thoughts in this entire passage are pointing much more to Israel specifically than to Gentiles generally, IMO.

According to Jesus and Peter, it was the religious elites, typically Jews, who were suppressing God’s truth (18) cf. Lk 11:52; Acts 15:10 et al. What was known of God had from the first been made manifest among them, Israel, in contradistinction to all others (19) cf. Amos 3:2; Deut 7:6. They Israel knew God (20) cf. Rom 9:4-5. And, Israel not the Gentiles knew God’s righteous judgements (32) and thus the consequences of the likes of Lev 18, of which we know elsewhere are numerous like references, etc.

Just a thought…

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us. 19For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. 20For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope 21that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. 22For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. 23And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. 24For in this hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what he sees? 25But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

Andrew, verse 22 alone makes it clear this has nothing to do with the physical. It’s clear there is a distinction between the “creation” and the “whole creation”. The creation is the creation. If the physical were in view one couldn’t have two entities.

The first creation (Israel) was longing for the sons of God/first-fruits (see verse 23) to be reveal. Once they were revealed, Israel (the creation) could be set free from its bondage to corruption. After that the Gentiles who have also be groaning (together they make up the whole creation) could now be grafted in.

@Rich:

That seems rather implausible to me. On what ground is “the creation” identified with Israel? Surely the whole point of Romans 9-11 is that Israel has not been eagerly waiting for the sons of God to be revealed. And why on earth would we think that “the creature” and “every creature” refer to two things?

For reasons already given, I would suggest that hē ktisis in 8:19-21 is in effect the “creature” of 1:23 which has been forced to serve, against its will, as an object of worship in place of the creator.

The creature, the material object, longs for liberation from its subjection to the futility of idol worship. Paul then expands on this to speak either of “every creature” or perhaps of “the whole creation” groaning together and in pain together.

Recent comments