The text argues that what we call “Christianity” is the religion shaped by the West, emerging not directly from the New Testament but from the historical development of Christendom. The New Testament anticipated Christ’s triumph over pagan empire, not a new civilisation’s structure. Modernity disrupted Christendom with secularism and historical readings of scripture. Shortt defends Christianity as vital cultural heritage but blurs the difference between the historical Jewish Jesus and later theological constructs. The Gospels stress God’s kingdom and eschatological hope, not abstract love. Theology later reinterpreted Jesus’ role, but history reveals faith rooted in concrete crises, demanding fresh retelling today.

What we call “Christianity” is the religion of the formerly Christian West. It survives residually in both the historic and modern churches, and globally as a result of both historic and modern missionary expansion. It is defined by diverse, overlapping systems of belief and practice, which generally speaking determine how the scriptures are to be read.

This Christianity is not found in the New Testament except inasmuch as a new civilisation is foreseen in which Christ Jesus is acclaimed as Lord to the glory of the one God who made all things and chose in Abraham a people for his own possession, etc. The New Testament does not prescribe the shape or workings of this civilisation, only the narrow and painful path that the churches of the Greek-Roman world would have to follow in order to get to it.

John’s “marriage supper of the Lamb” (Rev. 19:7-9) is the wedding that brings the man biblical storyline to a close—the climactic celebration of the triumph of the crucified messiah and his persecuted witnesses over the deadly pagan empire. But weddings are both endings and beginnings and we are given no indication how married life would work out.

In any case, modernity has changed this state of affairs in two key respects.

First, it has brought to an end Christendom as a socially and politically constructed worldview, laced together by the creeds, and has replaced it with what for convenience we call “secularism.”

Secondly, it has taught us to read the Bible historically, which means, happily, that as we go through our own end-of-the-age crises, we are much better equipped to learn from the end-of-the-age crises that shaped the events and ideas presented in the New Testament.

History is both the problem for western Christianity and the solution.

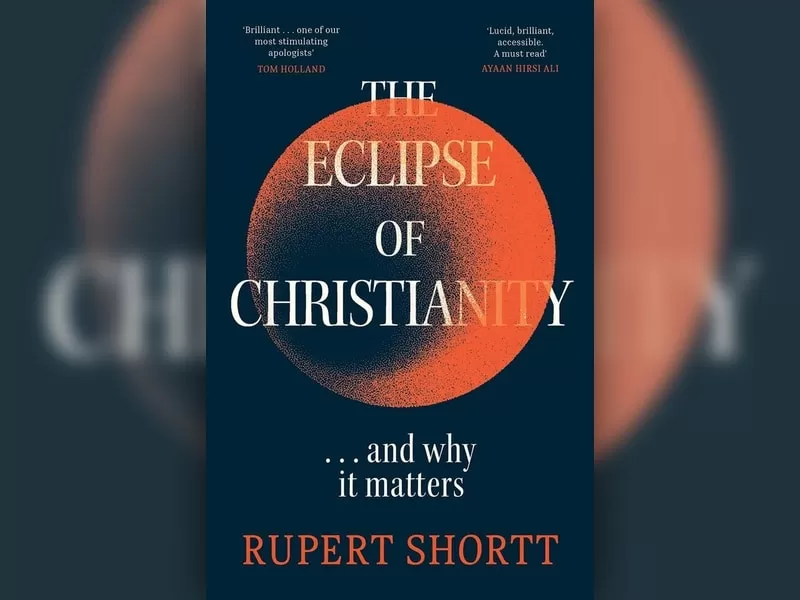

The nature and urgency of the rethinking involved can be illustrated from a section on “The Jesus of History and the Christ of Faith” in Rupert Shortt’s book The Eclipse of Christianity: And Why It Matters. In summary, the book defends historic Christianity as “the foremost expression of human culture” and puts forward the view that western societies neglect their theological roots at their peril.

Which Jesus?

Shortt begins the section with a quote from the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams:

By listening to what Jesus says, and by watching what he does, people’s whole sense of their world changes… Reading [the New Testament] is like watching people feeling their way into the new landscape and seeing the light in it. Bit by bit people put together a jigsaw and you end up with that really strange and mind-bending notion that God… lives in Jesus in an absolutely unique way….

I find that quite extraordinary. Presumably Williams is not wrong, and it really happens, but which Jesus are we talking about here? The first century Jewish prophet-Messiah utterly preoccupied with the fate of his people, whom we see in the Synoptic Gospels? The Jesus sharply differentiated from and at odds with the “Jews” in John’s Gospel? Or the Jesus of one contemporary piety or another projected back on to the gospel accounts?

Did those who encountered him in the Gospels really arrive at the “strange and mind-bending notion” that God lived in him? And if they didn’t, why should we? Something quite different is at issue in the Gospels—not the presence of God in Jesus but an authority that will have devastating future consequences. It is not the love of God that is proclaimed but the kingdom of God. “Kingdom” means “kingdom”; it does not mean “love.”

The fully human one?

Very loosely, from the theological perspective, Jesus is understood to have proclaimed and to have embodied the love of God, expressed especially in the renunciation of violence, compassion towards the poor and weak, the expulsion of evil spirits, and “those resources of generosity and compassion which are so easily deflected by social convention and spiritual legalism.”

In a Church Times article, Shortt says that the “greatest story ever told” is the one about “love’s mending of wounded hearts.”

So Christian theology is the product of two elements: “the actions and the words and sufferings of this particular human being, and the vision of a God whose purpose is unrestricted fellowship with the human beings that he has made.” The death and resurrection of Jesus have ushered in a “new phase in history,” in which people “discover their destiny in an orientation towards the source of their being.”

But why does it take the crucifixion of Jesus to bring about this new state of affairs?

Shortt gives two reasons; first, Jesus scandalised the Jewish authorities by claiming that his teaching fulfilled the Law of Moses; secondly, it is a general human trait to “despise and reject full humanity when we encounter it.”

The explanation is problematic on both accounts.

First, while the chief priests and the elders were certainly upset by what Jesus’ had to say about the Law, what finally got him killed was the declaration that the Son of Man who suffered many things would be given royal authority by YHWH to judge and rule over Israel:

And Jesus said, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.” And the high priest tore his garments and said, “What further witnesses do we need? You have heard his blasphemy. What is your decision?” And they all condemned him as deserving death. (Mark 14:62-64)

Secondly, I don’t think that anything is said in the New Testament to the effect that Jesus was thought to represent “full humanity.” This is an accommodation of the historical Jesus, who is the only Jesus we have, to a modern humanistic value system.

The most that we can say, as far as the New Testament witness goes, is that he represented an ideal, male, Jewish response to the religious and political crisis faced by Israel in the first century. To be conformed to his image was to be persecuted as he was persecuted, to suffer as he suffered, to die as he died, and to share in his resurrection life.

The “Father’s will” was not that he should be “completely human” but that through the suffering of Jesus and his loyal followers the kingdom should come, on earth as in heaven—that government on earth should conform to government in heaven. This is an eschatological or apocalyptic expectation. The enduring love of God towards his people is in there somewhere, but that is only a secondary concern.

It’s where we ended up, not where we started

Shortt goes on to say that the impact of Jesus’ life was “so extraordinary that it took centuries for the Church to reconceive its understanding of the divine nature.” But that merely highlights the immense gulf between the historical, Jewish Jesus and what the new Christian civilisation came to make of him.

As the kingdom expectation was fulfilled through the witness of increasingly gentile churches, the role of Jesus shifted dramatically: from the Son seated at the right hand of the Father, to whom authority had been devolved for an eschatological purpose, to the Son who is eternally “of one substance with the Father.” We are now in a very different conceptual-linguistic world—in Oz, not in Kansas—even if for good reasons.

Shortt is very dismissive of what he calls the “‘unadventurous’ model of God and his deputy,” according to which “the promised outcome was an authorised communication from God that would help us to lead better lives and to pray with a bit more confidence.” But that is a hopelessly inadequate account of the faith of the early churches in the one whose sufferings they shared quite realistically, in whose glory and rule they also expected to participate. Scripture and history demand something far better than this trivialisation of the “deputy” model:

This Jesus God raised up, and of that we all are witnesses. Being therefore exalted at the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured out this that you yourselves are seeing and hearing. For David did not ascend into the heavens, but he himself says, “‘The Lord said to my Lord, “Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool.”’ Let all the house of Israel therefore know for certain that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified.” (Acts 2:32-36)

Peter’s programmatic statement cannot be dismissed as a primitive and provisional construal on the way to a fully explanatory, trinitarian account of the relation between the Father and the Son. It was the whole faith of the early church in Jerusalem and needs to be read as such. It was transitional only to the extent that judgment against the Jew would be followed by judgment against the Greek and the glorious rule of this same crucified “Lord and Christ” over the nations of the Greek-Roman world (Rom. 2:9; 12:15).

The muddle that results from the theological interpretation of scripture is also evident in Shortt’s assertion that the Church “holds that an axe was laid to the roots of evil through the passion and resurrection.” At best, the words of John the Baptist have been used metaphorically; at worst, they have been completely misunderstood. John said that the axe of divine judgement was laid to the root of the trees of an unrighteousness nation and that Jesus would soon come with his winnowing fork to “clear his threshing floor and gather his wheat into the barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (Matt. 3:10-12).

Death and resurrection are just means to this historical end. To jump from the preaching of John the Baptist to a discussion of the “variety of theories” that purport to explain the atonement is incoherent—far too great a jump for theology to be a meaningful interpreter of history.

The scandal of particularity

So yes, there is a “scandal of particularity,” as Shortt notes. But it is not that the large, universal and eternal “verities” of Christian theology have been made contingent upon the circumstances of Christ’s life and death: why is the “unrestricted fellowship” of God with humanity dependent upon “the actions and the words and sufferings of this particular human being”?

It is that the encounter with God is always bound up with the chaotic historical experience of a priestly community. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus gain their meaning at a particular moment in that historical experience. But so also do the supposedly “eternal verities” of European Christian theology, and history is forcing us to reconsider how the story should be told from now on.

We are back in Kansas to get our historical bearings again.

Andrew, it’s been a while (transition back to the US, new employment, etc.), but I have continued to follow your work and on the whole I continue to track with your construal of Jesus, Paul, and the New Testament, with anabaptist questions and quibbles here and there. I’m wondering, here, whether there is a return of “judgment of the nations” in your thinking. It’s just my impression (that I haven’t confirmed by re-reading the last few years of your blog), but it has seemed like “judgment, first for God’s people then for the nations” has been largely replaced by “judgment of God’s people and conversion of the nations” in your recent writings. So, it caught my attention when both make there appearance in this post: “It was transitional only to the extent that judgment against the Jew would be followed by judgment against the Greek and the glorious rule of this same crucified ‘Lord and Christ’ over the nations of the Greek-Roman world (Rom. 2:9; 12:15).” In any case, when we read the NT and early church history narrative-historically, we have a significant account of what “judgment of God’s people” looked like (e.g., destruction of the temple), along with an account of the “conversion of the pagan empire to Jesus as Lord” (e.g., Christendom). But an account of “judgment against the nations” seems non-existent in our extant literature. At least there doesn’t seem to be any judgment of the nations that is as vivid and catastrophic as the “judgment of God’s people”. Or have I missed something? But shouldn’t we expect, narratively, something akin to the judgment of Israel to appear with judgment of the nations? If not, why not? On what narrative grounds is the judgment of the nations so much softer (at best) than the judgment of Israel? Relatedly: what is the narrative-historical basis of speaking of judgment and conversion of the empire? And given that basis, how was a relationship between judgment and conversion understood?

@Tim Peebles:

Hi Tim. Very good to hear from you. To save you reading the last few years of my blog here’s a quick overview of the judgment theme in the New Testament. You’re right, judgment of the nations is less concretely conceived—partly because the Greek-Roman oikoumenē was a much bigger and more complex entity than Jerusalem, but mainly, I would think, because the expectation was that YHWH would put things right by means of the witness of the churches rather than by military means.

Recent comments