My last post dealt with some specific texts which Paul K. suggested do not fit the kingdom paradigm that I am proposing. A more general question raised in his comment has to do with the relation of the story about kingdom to the theme of creation. Paul agrees that “there is something bigger and fuller going on than individual salvation and individualistic Christianity” but thinks that it is God’s story, not Israel’s story, that should be at the heart of the interpretive framework. He takes the kingdom narrative back to Genesis 1, where Adam and Eve are “given the commission to rule the earth (under God’s rule)”.

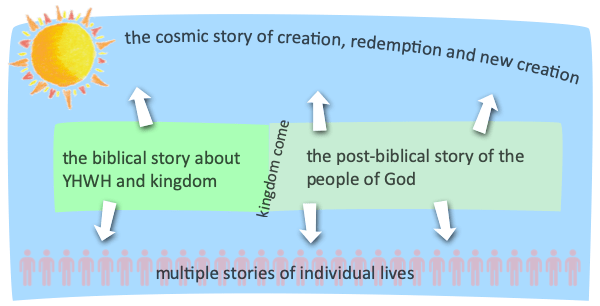

There are three narrative levels in the Bible—this is implicit in Paul’s comment. At the top there is an overarching story about God and creation. At the bottom there are innumerable individual stories. Between the two there is a story about Israel as a people struggling in the course of history to maintain its identity and vocation in engagement, for better or for worse, with the nations.

The question is which of these narratives is the controlling one. Which fundamentally determines the meaning of words such as “kingdom” and “gospel”? Which narrative tells us who Jesus is? We agree that it’s not the bottom story about individuals. But we perhaps disagree about the relation between the middle and top narratives.

The middle narrative barely features in modern theologies unless you are some sort of dispensationalist. Or perhaps an allegorist. But it seems pretty obvious to me that this is the storyline that overwhelmingly dominates scripture, from the “election” of Abraham in the shadow of Babel, through profoundly transformative clashes with Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and the Greeks, to the climactic overthrow of Babylon the great, Rome, the idolatrous and satanic persecutor of the churches.

It is in this narrative stratum, in my view, that the argument about kingdom belongs. So I note, for example, that the Old Testament passages that are most influential in shaping the New Testament vision of the kingdom are all political texts that speak of the rule of YHWH or his king or his people over the nations (notably Pss. 2, 110; Dan.7), or the deliverance of Israel from oppression—the Aramaic version may or may not go back to the disciple of Hillel, but it at least highlights the relevance of these passages for understanding Jesus’ proclamation:

Go up on a high mountain, O prophets who proclaim good news to Zion; lift up your voice with strength, you who proclaim the good news to Jerusalem, lift up, do not fear; say to the cities of the house of Judah, “The kingdom of your God has been revealed.”

How beautiful upon the mountains of the land of Israel are the feet of the one proclaims good news, who causes to hear peace, who proclaims good, who cause to hear deliverance, who says to the congregation of Zion, “The kingdom of your God has been revealed.” (Is. 40:9; 52:7 Targum Jonathan)

I also made the point in the previous post that texts which out of context perhaps suggest broader Wisdom sentiments, such as Jesus’ exhortation to seek first the kingdom of God, always presuppose an eschatological argument about how God is judging and restoring Israel. [pullquote]I don’t see either Jesus or Paul taking the argument back to Genesis 1, as though the coming of the kingdom of God would be a restoration of humanity’s sovereignty over the non-human world.[/pullquote]

Similarly, our theologies tend to locate the story of Jesus either at the top or at the bottom of the multi-storied world of scripture. On the one hand, he is the divine Word through whom all things were created, who became flesh in the middle of history to deliver humanity from its bondage to sin, and who will judge the living and dead at the end of history. On the other, he is my personal Saviour, who died for my sins, and is now my best friend.

My argument, however, is that it is the middle narrative about Israel and the nations, looking backwards and looking forwards, that mainly frames and interprets the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. In this narrative he dies for the sins of Israel in order not only that God’s rebellious people might have a new future in the ancient world but also that the nations might become subject to the God of Israel. His death and resurrection will have implications for the cosmos (cf. Rom. 8:19-22), but that is not what the narrative is driving at.

If the middle narrative is given its proper biblical weight and prominence, it becomes apparent that it determines the significance of the two other levels.

1. Throughout scripture the fate of individuals is bound up with the fate of the people of God. So, for example, Zacchaeus is not just an individual who is saved by his belief in Jesus. He is a wealthy and typically dishonest Jewish tax collector who is restored to the family of Abraham by one who claimed to “fulfil” Daniel’s vision of a persecuted “son of man” figure, who comes on the clouds to receive authority over the nations (Lk. 19:1-10). [pullquote]That is, his salvation is part of Israel’s story and counts for nothing outside of that framework—and I don’t see why that shouldn’t give us the template for “personal salvation” today.[/pullquote]

2. The story of Israel is the story of how the creator God has responded to humanity’s fundamental disobedience and self-determination. But then it seems to me that what happens is not that the apostles and New Testament scriptures start to reveal God’s eternal purpose for creation but quite the opposite: the creation narrative serves to interpret what is happening in the middle level narrative about Israel and the nations.

The story of Adam and Eve is as much a typology of the exile as an account of human origins. The family of Abraham will be a new creation in microcosm in the land. Restored Judah will be like Eden (Is. 51:3); it will be as though God has made new heavens and a new earth (Is. 65:17-18; 66:22). Negatively, the Prince of Tyre was like Adam in Eden but his heart has become proud (Ezek. 28:1-19). The resurrection of Jesus anticipates—and, I think, necessitates—a new heaven and a new earth, but in the narrative it constitutes the “resurrection” of punished Israel on the third day (Hos. 6:1-2). Paul’s description of Jesus as a new Adam is part of an argument about the condemnation and justification of Israel (Rom. 5:12-21) or the liberation of Israel from the power of the Law (1 Cor. 15:45, 56-57).

I can understand why from the modern post-imperial, socio-ecological perspective it would seem desirable to give greater prominence to the creational story than to a historical narrative which, as I see it, culminates in the conversion of the Roman empire. But, of course, the New Testament wasn’t written from the modern perspective. It was written from within the historical narrative of first century Israel, and it seems quite reasonable to think that from that perspective the political-religious crisis had interpretive priority over the bigger story about God and creation. In that regard, God’s story was Israel’s story—and I don’t see why we shouldn’t allow it to run through to the present day to give us the narrative basis for our own self-understanding.

“…to the climactic overthrow of Babylon the great, Rome, the idolatrous and satanic persecutor of the churches.”

I think the payoff from your approach is huge, and I agree that Scripture is almost all about Israel. But this quoted sentence is the sticking point for me. When did it happen? Alaric? The history of Rome doesn’t come to a satisfying catastrophe like the history of Assyria, Babylon, and Antiochus’ Greco-Syrian empire. Indeed, so non-obvious was this “overthrow of Rome” to Christians that they continued to think of Rome as the source of power. That is why an anonymous Gregorian Reform author forged the Donation of Constantine. It is also why Charlemagne, a Frank, not a Roman, called himself Caesar; why Russia had Tsars; why there was such a thing as a Holy Roman Empire.

It bothers me a lot. Everything the Scripture says about those who persecute God’s people leads us to expect that God will violently destroy them. But this never really happens to the Romans. If, on your view, Babylon in Revelation is Rome, then we should expect to see a moment in history when God’s vengeance on her for the persecution of His Church is obvious to all. Instead, we find the opposite.

Does this bother you?

Good questions, Matt, to which I may not have satisfactory answers.

1. I would stress that we should still read the New Testament forwards and not backwards. Hindsight is unavoidable at some level, but the meaning of New Testament apocalyptic is not determined by the shape of what actually happened.

2. I would argue that it is not Rome, as such, or empire in general terms that is judged but Rome as a pagan, idolatrous power, demonically inspired, and hostile to the people of God. The Bible is not anti-imperial, certainly not to the extent we would perhaps like it to be—consider Daniel 4:34-37. I don’t think “the empire of YHWH” is a contradiction in terms.

3. I’m not sure about the violent destruction part with respect to idolatrous Rome. The point appears to be that it is defeated by the Word of God and the faithful witness of the saints to the truth of Jesus’ resurrection and its implications for the future of the ancient world.

4. The apocalyptic expectation is primarily that persecution will come to an end, that the suffering churches will be vindicated—not forgetting the dead—and that Christ will be confessed as Lord by the nations, to the glory of the one true, living creator God. There is also Lactantius, Of the Manner in Which the Persecutors Died, to consider.

Zacchaeus is not just an individual who is saved by his belief in Jesus. He is a wealthy and typically dishonest Jewish tax collector who is restored to the family of Abraham by one who claimed to “fulfil” Daniel’s vision of a persecuted “son of man” figure, who comes on the clouds to receive authority over the nations (Lk. 19:1-10).

How do you get from the description of Zacchaeus’s restoration in the first part to the association of Jesus with the Daniel 7 prophecy in the second part? There is no mention of the latter in the Zacchaeus story.

Zacchaeus’s ‘restoration’ to the family of Abraham has to be taken in a very qualified way. It shows rather that Jesus was bringing salvation to those regarded as sinners by “all the people”, those presumably regarding themselves as within the Abrahamic family, according to the same narrative which you assert to be the main biblical story.

The Zacchaeus story highlights something very different, that the narrative presumed by Israel which excluded the likes of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:7), was taking a completely unexpected turn. We should have been alerted to this all along by the appearance of Jesus as a very different messiah from anything expected by Israel.

In the light of this difference, we might also expect that the anticipated overthrow of idolatrous pagan oppression was not going be the paradigm controlling the story. This proved to be the case. In fact Jesus has nothing to say about this outcome, which might have been expected in the light of your interpretation of the meaning of the Daniel prophecy. Rather, he approves of the Romans he encounters in the story (Pontius Pilate excepted, though even here the encounter can hardly be described as antagonistic). It was the overthrow of unbelieving Israel which Jesus predicted, and which historically took place.

I find as many problems as there are solutions in your adaptation of the narrative into the middle band.

@peter wilkinson:

How do you get from the description of Zacchaeus’s restoration in the first part to the association of Jesus with the Daniel 7 prophecy in the second part?

By compressing a lengthy argument into a few words. It is the Son of Man who saves the lost Zacchaeus, and I am firmly of the view that the Son of Man motif in the Gospels consistently evokes Daniel 7.

I don’t understand what you mean about the restoration of Zacchaeus having to be taken in a qualified way. But my point was simply that he is saved not as a generic individual but as a participant in Israel’s story. Clearly something unexpected is happening, but it is still happening within the story of the family of Abraham.

In the light of this difference, we might also expect that the anticipated overthrow of idolatrous pagan oppression was not going be the paradigm controlling the story.

I agree that Jesus does not predict the overthrow of pagan Rome. His attention is directed to the coming judgment on unbelieving Israel with at best a marginal expectation that he will judge the nations according to how they treat his disciples in the coming decades. He might have taken the story further, but he didn’t, for reasons best known to him. It was left to the apostles, as they proclaimed the resurrection in the pagan world, who drew the conclusion that this must inevitably lead beyond judgment on the Jew to judgment on the Greek.

In this narrative he dies for the sins of Israel in order not only that God’s rebellious people might have a new future in the ancient world but also that the nations might become subject to the God of Israel.

In keeping with the importance of a hermeneutic that takes seriously narrative context, I would substitute “he dies for the sins of Israel…” with “he was made Lord and Messiah so that God’s rebellious people might…” simply b/c the louder message of the Christ-event for Jews (as evidenced in the messages spoken to Palestinian Jews in Acts 2-5) seems to be the fact of the enthronement of the Messiah. The details of the pathway/basis for his enthronement (perfect obedience, suffering servant/ vicarious death, vindicated resurrection) are vaguely asserted in these contexts, and Jesus’ vicarious death for Israel’s sins is notably absent. The word preached to Palestinian Jews as recorded in Acts in response to Jesus’ appointment as Messiah was “repent.. in the name of Jesus the Messiah” (Ac 2:38) that is, “believe that God saves Israel through the name of the Messiah” not “believe in Jesus the lamb of God and his sacrifical death on the cross for your sins.” If narrative context is important for exegesis, and if the middle narrative deserves the most attention, then the message preached to Palestinian Jews in Acts 2-5 should probably be given prominence.

@Charles:

I fully agree with your reading of Acts, but there may be a danger of pushing the argument too far in that direction. I’m inclined to think that Isaiah 53 is an important factor in the apostles’ reflection on the significance of Jesus’ death. The Maccabean traditions bear witness to the idea that the death of a martyr has atoning significance. Paul clearly regarded Jesus’ death as more than a pathway to enthronement: “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15:3). So while I think that the atoning function of Jesus’ death has been overstated, I wouldn’t myself want to suggest that it can be erased from the narrative altogether.

On this question generally I recommend David Brondos’ book Paul on the Cross: Reconstructing the Apostle’s Story of Redemption. For example, he argues that Jesus’ death “is certainly salvific and redemptive, but not in itself, and not through any “effects” it has. Rather, it is salvific and redemptive only in that it forms part of a story”.

Hi Andrew,

I think that is a really good point about the amount of time given to Israel story in the Bible, and especially the Old Testament – and one that, I’m embarrassed to say, I hadn’t fully appreciated before.

I’m still thinking through your post. But here are a few questions that come to mind:

Is the story about Israel and the people of God still the main (middle) narrative of New Testament?

Or is Jesus the main (middle) narrative of the New Testament?

When the apostles went out proclaiming the good news, were they telling Israel’s story or were they telling Jesus’ story?

Did Jesus exist as a man to fulfil God’s promises to Israel?

Or did Israel exist so that, through them, Jesus would come as a man and fulfil God’s purpose for himself and the whole of creation?

Paul

@PaulK:

This question gets to the heart of the hermeneutical problem. Traditional readings have tended to make Jesus the centre of the New Testament story—individuals are saved through their relationship with him, and the cosmos is potentially transformed by his resurrection from the dead. The New Perspective in New Testament studies and narrative-historical approaches have put Jesus back in the context of Israel’s story. He remains supremely important, both for individuals and for the cosmos, but not apart from the story of a people.

So the angel says to Joseph that Jesus will save his people from their sins. Jesus’ ministry in the Gospels is not about himself, it is about Israel, culminating in a lengthy account of what will happen to the nation within a generation. Or another example, the Lord’s prayer, when read contextually and intertextually, becomes a prayer about the restoration of Israel through the witness of a marginalized community. Why does Acts begin with a question about the restoration of the kingdom to Israel? Why do we have Romans 9-11? Why does Revelation climax in judgment on Rome? The whole New Testament, once you start looking at it this way, is seen to be the story of what YHWH is doing in and through and for the sake of his people, including sending his Son on a dangerous mission to the vineyard in search of its fruit.

So contrary to predominant evangelical sentiment, it’s not all about Jesus—it’s all about us as God’s people, called in Abraham to walk with him through history as his people, subject now to Jesus Christ as Lord, filled with the Holy Spirit, but still required to be new creation in the fullest terms. The narrative-historical approach fundamentally addresses the question of why we are here.

Recent comments