I have to say, I have enjoyed my conversation with Carl Mosser about theosis as an account of what it ultimately means to be redeemed. I still don’t really get it. That may have something to do with language—an “allergic reaction” on my part to the “deification terminology”—but it clearly has a lot to do, too, with different understandings of New Testament eschatology.

In a comment, Carl briefly set out the eschatological frame for an understanding of redemption that might be restated in terms of theosis or deification.

1. What is “presently true of the Son in his resurrected, ascended, glorious humanity will be made true of the redeemed”.

2. This is what is meant by the quite widely used imagery of “firstfruits”, “firstborn”, “first among many brothers” (1 Cor. 15:20; Col. 1:18; Rom. 8:29; cf. Heb. 2:10-11). What Jesus experiences first, the redeemed will experience later.

3. Comprised in this condition of glorious new humanity are “all the NT themes that are tied together in the patristic concept of deification: union with Christ, being one with the Father and Son, being filled with the Spirit and the fullness of God, adoption to divine sonship, being begotten with imperishable seed, being raised immortal and incorruptible, sharing in the glory of God, being made a new creation, growing in likeness of Christ, restoration of the divine image and likeness, imitation of God, undergoing ethical transformation, and so forth”.

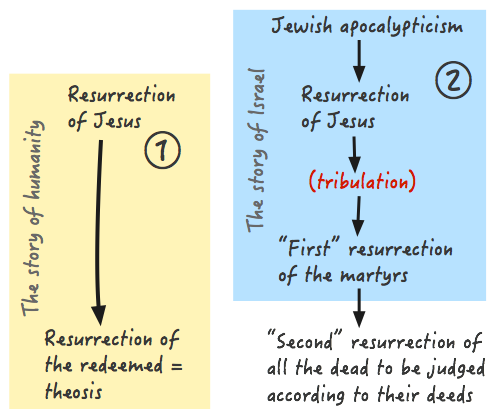

My guess is the most evangelicals would baulk at the introduction of the word “deification” but would otherwise broadly affirm such an account of the relationship between Christ’s resurrection and that of the redeemed. My argument is that the relationship is more or less sound but has been wrongly framed. So in the interest of clarity, I will set the two schemes side-by-side.

1. The politics of resurrection

The conventional account assumes the widest possible scope for resurrection. Jesus is raised as a second Adam, the beginning of a new humanity constituted of the redeemed, which is such a comprehensive participation in the glory and life of God that it is not an exaggeration to call it a theosis (1).

The New Testament, however, does not for the most part speak of the resurrection of Jesus as the means by which he assumes a new “glorious humanity”. What he gains as a consequence of his resurrection and exaltation to the right hand of God is lordship or authority. Sitting at the right hand of God is itself a symbol of royal status. In order to gain that lordship he must be raised from the dead and must therefore be the beginning of a new humanity, but that is not the principle objective. The objective is the political one—to exercise sovereignty.

So my contention is that New Testament eschatology is fundamentally and irreducibly political—or perhaps better political-religious—in the sense that it belongs mostly to the story of YHWH’s rule over his own people and the nations in history. This sets narrative boundaries to the significance of resurrection.

New Testament eschatology assumes an apocalyptically coherent chronology: a period of “tribulation” or “distress” as the churches bear faithful witness to the resurrected Jesus as Lord, culminating—in a foreseeable future—in judgment on the pagan world and on Rome in particular, the confession of Jesus as Lord by the nations, the vindication of the churches, and the inauguration of Christ’s reign over the nations accompanied by the resurrected martyrs (2). This corresponds, conveniently, to John’s “first resurrection” of the martyrs. His “second resurrection” of all the dead is actually of only marginal interest to the New Testament (Rev. 20:4-6, 12-13).

2 Thessalonians 1:5-2:12, for example, is a much neglected passage in modern constructions of Paul’s eschatology (partly, of course, because of doubts over authenticity), but it is a detailed description of the resolution at the parousia of an immediately relevant political-religious crisis. The Thessalonian believers are suffering persecution, but when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven with his mighty angels, he will bring an end to their suffering and punish their enemies. This may take longer than they would like—certain events must first unfold, having to do with a Nero-like “man of lawlessness”. But Paul’s language stitches this predicted “end” tightly into the fabric of a realistic historical expectation.

Because we have no direct interest in the political dimension of Jewish apocalyptic—usually because we assume it belongs to a remote future rather than a remote past—we filter it out, which leaves us with the sort of generalised, humanity-oriented eschatology that may be reformulated in terms of theosis.

2. Firstborn of those who would suffer

The Jewish background to resurrection has to do not with the renewal of humanity but with the restoration of Israel and in particular the vindication of the martyrs. It’s not a global or cosmic event but a national event (cf. Dan. 12:2-3). It is something that happens at a time of national crisis.

In the New Testament story the resurrection of Jesus anticipates this resurrection: he is Israel raised from the dead on the third day (cf. Hos. 6:1-2); he is the Son of Man who embodies in himself, or otherwise represents, the saints of the Most High against whom the blasphemous little horn on the head of the fourth beast—a type of “man of lawlessness”—made war.

The fundamental ground for his relationship with those who are raised at the parousia, when he comes to defeat the political-religious enemies of his people and establish his own rule over the nations, is that they have suffered as he suffered. This, I think, is what is in view when Jesus is described as the firstfruits or firstborn from the dead (1 Cor. 15:20; Col. 1:18), the firstborn of many brothers (Rom. 8:29), who would bring many sons because he suffered as they would have to suffer (Heb. 2:10-18).

This is especially clear in Romans 8:12-39. The chapter is usually read as a general account of what it means to be Christian, but I think Paul’s argument is more sharply focused than that, controlled by a pressing apocalyptic narrative.

1. Believers are children of God because they have the Spirit, but they will be “heirs with Christ” if they suffer with him, and if they suffer with him, they will be glorified with him (8:17).

2. The sufferings of the present eschatological period are not worth comparing to the glory of the age to come, when Christ will be confessed by the nations and the churches will be vindicated for having served him faithfully (8:18).

3. Creation looks to the redemption of the suffering churches for an assurance of its own eventual liberation from its bondage to decay (8:19-22).

4. Those who are called to follow this path are being “conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers” (8:29). Again, in the context this is not a general moral-spiritual Christlikeness. It is the conformity of those who are suffering to the image of the one who suffered, died and was vindicated by his resurrection from the dead.

5. Those who are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered will be conquerors, as Jesus conquered, and will not be separated “from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (8:35-39).

Paul’s very personal admission that he expects to share in Christ’s sufferings, “becoming like him in his death”, in the hope of experiencing the power of his resurrection (Phil. 3:10-11), also fits neatly into this paradigm.

3. Inheritance of the kingdom

What the suffering church is said to inherit, finally, is not the personal transformation that comes with resurrection and theosis but the kingdom, understood in this-worldly and political-religious terms. Christ and the martyrs reign from heaven, but they reign for the sake of the life and mission of the people of God on earth while time lasts.

The close connection between inheritance and kingdom is everywhere apparent. Jesus says that the meek will inherit the earth or the land (Matt. 5:5). The twelve will sit on thrones judging Israel when they inherit the life of the age to come (Matt. 19:28-29). The Son’s inheritance is not a glorious new humanity but the vineyard of Israel (Matt. 21:38). Righteous Gentiles will “inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (Matt. 25:34).

Faith is the means by which the descendants of Abraham will inherit the world (Rom. 4:13; Gal. 3:18; 3:29). The unrighteous will not “inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 6:9; Gal. 5:21; Eph. 5:5). Those who are raised inherit the kingdom of God (1 Cor. 15:50). The “glorious inheritance in the saints” derives from the fact that Christ has been seated at the right hand of God, above all rule and authority, etc. (Eph. 1:18-21). Those who share in the inheritance of the saints have been transferred to the kingdom of the Son (Col. 1:12). God has chosen those who are poor to be “heirs of the kingdom” (Jas. 2:5).

This is not every reference to inheritance in the New Testament, but it is hard to discern any other coherent theme that would explain the concept. The supreme attainment of the saints is not transformed humanity but kingdom, understood as reigning with Christ throughout the coming ages.

Significantly—or perhaps just coincidentally—Psalm 82, which features prominently in the arguments about theosis, ends with the cry, “Arise, O God, judge the earth; for you shall inherit all the nations!” In my view, the New Testament tells us how this will come about—through the faithful witness of a persecuted community whose suffering and vindication is anticipated in the death, resurrection and exaltation of Jesus.

Andrew, I’ve read this post and your follow up a couple times. I’m left with a lot of questions about your views best discussed in person, should our paths cross. It will come as no surprise that I disagree with your reading of certain texts and think the tail of your distinctive eschatological framework is wagging the exegetical dog. However, in several places where you present your views as at odds with deification, I don’t see any conflict. As you depict your view in the graphics, there is no tension whatsoever. So, I am a bit mystified as to why you resist the idea that deification isn’t an apt description of what awaits the righteous when the cosmos experiences “its own eventual liberation from the bondage to corruption” and we enter into that which is “barely visible beyond the horizon.” If you don’t think the NT gives us any hints about what happens then, then rather than oppose deification you should be agnostic.

In this post you actually say a great deal with which I either agree or might be persuaded. However, the difference between us is that you seem driven by a reductionistic impulse that severely limits the scope of many texts to imminent political realities. I can agree with many of the referents but would contend that these texts also point beyond those circumstances to additional and deeper fulfillment in the new creation. Thus, repeatedly on my printout I wrote “not either/or” and “false dichotomy.” Its not kingdom or deification; its not lordship/authority or glorious humanity. The texts themselves point to both. Daniel provides a nice example.

Daniel is clearly concerned with imminent political-religious crisis. The dominion, glory and kingdom given to the son of man relates to the destruction of competing kingdoms and dominions. Furthermore, the kingdom and dominion is given to the saints of the Most High and “their kingdom shall be an everlasting kingdom, and all dominions shall serve and obey them” (7:27). But the language of “dominion” also takes us back to creation themes in Gen 1 and Ps 8. We have here something that points both to the restoration of Israel and transcendent eschatological realities that will manifest in the new creation. This becomes especially clear in ch. 12 where the description of resurrection takes up the explicit language of astral deification: “And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, like the stars for ever and ever” (12:3). They will be clothed with glory, as the ascended Christ now is (Ps 8/Heb 2). Daniel’s description of resurrection points beyond the political restoration of Israel to the glorious transformation of the saints. Its not one or the other but both.

We find this same vision of glorious transformation throughout Jewish apocalyptic literature and deeply embedded in NT ideas such as: “the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father” (Matt 13:43), being called into God’s “own kingdom and glory” (1 Thess 2:12; cf. 1 Pet 5:10; 2 Pet 1:3), called to “obtain the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ” (2 Thess 2:14), “the hope of glory” (Rom 5:2; Col 1:27), being “transformed from glory to glory” (2 Cor 3:18), the “eternal weight of glory” for which we are being prepared (2 Cor 4:17), appearing “with him in glory” (Col 3:4), partaking “in the glory that is going to be revealed” (1 Pet 5:1), and so forth. These texts do not point merely to an imminent political vindication or temporary millennial age. Rather, they go beyond those things to describe the transformation of the redeemed in conformity to the risen and ascended Christ. That entails an elevation and transformation of human nature, just as Paul clearly indicates in 1 Cor 15.

Finally, two things to note. First, throughout our discussion I’ve placed as much emphasis on ascension as resurrection, so I’m not sure why you focus only on the latter. Does your schema leave room for the ascended Jesus fulfilling Ps 8 as the archegos whose path we follow? If it does, then you’ve got a redeemed humanity crowned with glory and honor with all things subject in fulfillment of God’s intentions in creation that is not limited to resolution of a political crisis or millennial period. Second, I have not used the term theosis. Despite its popular use as a simple synonym for deification, this is problematic and generates no small amount of confusion in the literature. I prefer to reserve theosis for certain developments of the patristic doctrine of deification in accord with the word’s historical usage.

Carl, thank you for the thorough response. I love the clarity of your writing. Sorry it has taken a while to get round to replying.

However, the difference between us is that you seem driven by a reductionistic impulse that severely limits the scope of many texts to imminent political realities.

This is perhaps true. The reductionism is a little self-conscious, even a heuristic method. But it is also, in my mind, a deliberate push-back against the expansionist readings that aim to accommodate the biblical texts to one theological perspective or another. Frankly, I have found that, at both the micro and the macro level, the Bible makes better sense and holds together better when read forwards, according to historical assumptions, than when backwards, according to theological assumptions.

So I distrust the hermeneutic that allows that prophetic-apocalyptic texts may have further levels of meaning and reference beyond the immediate historical. It is too convenient. I am inclined to agree with Ben Meyer: “Neither Testament shows us prophets entertaining a compound, temporally disjoined perspective, both imminent and non-imminent” (Christus Faber: The Master Builder and the House of God, 47).

But the language of “dominion” also takes us back to creation themes in Gen 1 and Ps 8.

But the presence of the English word “dominion” doesn’t mean that the thought is there. There is nothing in Daniel to evoke the creational “dominion” over living creatures (Gen. 1:26-28; Ps. 8:6-8)—or, say, the associated mandate to spread and fill the earth. It is a dominion over nations, asserted in the context of a political crisis: “to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him” (Dan. 7:14). You can call this insistence reductionist, but I would say it’s simply reading what’s there rather than what’s not there.

We have here something that points both to the restoration of Israel and transcendent eschatological realities that will manifest in the new creation. This becomes especially clear in ch. 12 where the description of resurrection takes up the explicit language of astral deification…

Again, this seems to me an overstatement. What Daniel describes is the resurrection of some Jews following a great day of affliction for Israel. The nation will be “delivered” or “lifted up” (LXX). The righteous dead—presumably the martyrs—will be raised to the life of the age to come; the dead apostates will be raised to shame and contempt in the age to come. But they remain part of the life of the saved nation. They are not taken to heaven or to some transcendent existence in a new creation. Daniel’s resurrection is presumably a more literal one than we have in Ezekiel 37, but it is no less historical.

I’m not sure that Daniel includes the “wise” among the resurrected righteous, but supposing he does, they are only said to shine like the “brightness of the sky” and like the stars. Is this really the “language of astral deification”? Arguably, in biblical terms, the comparison with stars or celestial beings points to kingship (cf. Num. 24:17; 1 Sam. 29:9; 2 Sam. 14:17, 20; Is. 9:5). Antiochus Epiphanes exalted himself above every god (Dan. 11:36); the righteous gain such exalted kingly status through suffering. Brueggemann sees in this passage a movement “from dust to kingship”.

What we would then have here is the beginning of the apocalyptic motif of the reign of the martyrs, who lose their lives out of faithfulness to YHWH but who are eventually vindicated and reign over the nations—not over fish, birds, livestock and creeping things—in the age to come. In which case, resurrection here belongs to the political-kingdom narrative, not to a final renewal of humanity in a new creation. There is no need for a both-and: the point is simply that some of the dead, both righteous and unrighteous, are included in the ongoing life of the saved nation.

Jesus expects a similar crisis at the close of the age. He depicts the coming judgment on historical Israel as the separation of the weeds from the wheat at the time of harvest. In his telling of the story, there is no resurrection of unrighteous Jews—they are destroyed in the fire. The righteous will “shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father” (Matt. 13:37-43). But there is no “astral deification” here—no stars at all. He is speaking of the “glory”—the reputation—that the righteous will have in the age to come, in the people of God reconstituted and restored after the catastrophe of the Jewish War. Or so it seems to me.

What I would then point out with regard to the various texts that you cite having to do with sharing in Christ’s glory is that they all presuppose a pattern of Christ-like suffering followed by Christ-like glory. In effect, this is the Jewish martyr narrative being worked out according to a slightly revised template determined by Christ’s death, resurrection and exaltation to a position of glory in the ancient world.

- The Thessalonians have been called “into his own kingdom and glory” insofar as they “suffered the same things from your own countrymen as they did from the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all mankind by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles that they might be saved” (1 Thess. 2:14–16).

- The assurance in 2 Thessalonians 2:14 that they will “obtain the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ” should not be separated from the preceding apocalyptic narrative about the deliverance of the persecuted Thessalonian believers from their enemies. They are worthy of the kingdom of God because they have remained faithful in all their persecutions (2 Thess. 1:4).

- Urging his readers to stand firm in their persecutions, Peter writes: “after you have suffered a little while, the God of all grace, who has called you to his eternal glory in Christ, will himself restore, confirm, strengthen, and establish you” (1 Pet. 5:10).

- Peter’s statement about sharing “in the glory that is going to be revealed”, is explained by 4:12-13: “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you. But rejoice insofar as you share Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed.”

- Paul rejoices in the “hope of glory” because it is a hope that arises out of suffering (Rom. 5:2-5). In 8:17 being glorified with Christ is made directly dependent on having suffered with Christ.

- It is the “momentary affliction” of his apostolic sufferings that is preparing the apostles (not all believers) for “an eternal weight of glory” (2 Cor. 4:17).

- The connection is a little looser in Colossians 1:27, but he has just affirmed that he rejoices in his sufferings and is busy making up the deficit between his own sufferings and Christ’s for the sake of the church. The remarkable thing is that the Gentiles have also been afforded the privilege of sharing in Christ’s suffering and vindication for the sake of the future of God’s people in the ancient world.

- The connection with suffering is not immediately apparent in Colossians 3:4, but given the reference in verse 6 to the coming wrath of God, it is not difficult to imagine the same apocalyptic narrative is lurking in the background.

So my argument here is less that the language of deification is inappropriate than that the apocalyptic narrative of which it is part is much narrower than the theological constructions allow. It is not about humanity and creation but about martyrdom and kingdom.

Finally, I agree that the ascension/exaltation of Jesus is integral to the significance of his resurrection in the New Testament context. I also grant that Hebrews uses Psalm 8 to speak of the “subjection of the oikoumenēn to come” to Jesus. This may well look beyond the immediate “political” horizon to a final defeat of death and renewal of creation (note Heb. 2:8b-9).

But I would still maintain that in Hebrews he is archēgos in that his suffering and vindication preceded the suffering and vindication of the many sons who were to be brought to the same glory (cf. Paul’s idea of firstborn among many brothers). This is apparent in Hebrews 12:2-4: Jesus is the archēgos of their faith—almost prototype—who endured hostility, but they have not yet “resisted to the point of shedding your blood”; and in a passage like 13:12-13: “So Jesus also suffered outside the gate in order to sanctify the people through his own blood. Therefore let us go to him outside the camp and bear the reproach he endured.” Suffering as Christ suffered is everywhere a crucial factor in the equation.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

Sorry for the delayed response. Thank you again for the push back. You raise objections I would not have anticipated, so its helpful. With conferences coming up next week, however, I’ll need to make this my last contribution to the discussion for a while.

- Reductionist readings can be used to accommodate biblical texts to one theological perspective or another as easily as expansionist readings. So, self-conscious reductionism cannot inoculate against that disease.

- You distrust a hermeneutic “that allows that prophetic-apocalyptic texts may have further levels of meaning and reference beyond the immediate historical.” I oppose those approaches that take all those texts to primarily refer to the distant future with little concern for the immediate context in which they were written and in which the first readers would have understood them. If that is what you have in mind, then we have similar concerns. However, when I look at the way Matthew 1-4 or Revelation, for example, make use of the OT it is entirely obvious to me that “prophetic-apocalyptic texts” do in fact have further levels of meaning and reference beyond the immediate historical. They can be “fulfilled” (in the Matthean sense) more than once and in more than one way legitimately.

- You are right that Daniel’s immediate focus is rule over the nations. But intracanonical allusions would not have been deemed insignificant by any ancient Jewish or Christian interpreter. The mindset that led interpreters to see significance in the co-incidence of words, phrases, and concepts was shared by the ancient authors who composed these works. So, it seems to me that you are not “simply reading what’s there” but rather allowing your reductionism to put a blinder in front of something that is actually quite prominent in the text.

- In a couple places you pit kingship against deification as if they are incompatible alternatives. They aren’t. Bruegemann’s phrase about movement from dust to kingship quite nicely captures an important facet of the doctrine of deification: the righteous will attain exalted kingly status, participating in God’s rule and reign as his image in the created order.

- “Glory” in the Bible sometimes refers only to reputation, honor, etc.; sometimes to the luminescent radiance of God’s holiness; and sometimes to both simultaneously. The passages I cited do not refer merely to reputation or honor. They presuppose the narrative of glory we find in early Jewish and Christian texts. In this narrative, Adam is understood to have bene clothed in glory, that glory was lost because of disobedience and corruption, and the restoration of that glory is a key eschatological hope. That restoration is partially anticipated in Moses’ radiance and the transfiguration.

- I fully agree that the passages I cited presuppose the pattern of Christ-like suffering followed by Christ-like glory—a point I’ve myself made on other occasions. But these texts neither address nor refer exclusively to those who will be martyred. Nor can their scope of reference be limited to the apostles. The experience of Christ and the apostles are paradigmatic and prototypical for the Christian community, not special cases that differ from that of believers generally.

- 2 Cor 4 is the only passage on the list for which I can see any kind of plausible case for delimiting the scope of reference to exclude believers generally, but only if you ignore its place in the letter and refuse to allow Paul an inclusive we/us/our that the broader context simply demands. In 2 Cor 1-6 Paul is indeed focused on his ministry and that of the other apostles. But its clear from the beginning of the letter he is not differentiating apostolic experience from the Corinthians’. Rather, he sees the experience of Christ, the apostles, and the Corinthian churches as organically connected: “we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings… you patiently endure the same sufferings that we suffer… as you share in our sufferings, you will also share in our comfort” (1:5, 7). As he does in 2 Thess, he puts his example forward as a model to imitate.

The suffering and glory he speaks of throughout are not reserved for the apostles or a special class of martyrs exclusively, but the people of God inclusively. What is true of Christ and true of the apostles is what is also supposed to be true for believers. Thus, throughout these chapters Paul’s we/us/our frequently includes the Corinthians themselves. We see this movement explicit when he says, “It is God who established us with you in Christ, and has anointed us, and who has also put his seal on us and given us his Spirit in our hearts as a guarantee” (1:22). Guarantee of what? The ministry of the Spirit and righteousness that brings more glory than even Moses experienced, and glory that will be permanent (3:8-11). This is not for the apostles alone, because “we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (3:18). The “we all” here is not “all us apostles” but all who experience the ministry of life found in the new covenant (cf. 3:7, 14) for whom the veil has been lifted through Christ (3:14). It is for all believers, those who receive “the gospel of the glory of Christ” (4:4) and are given “knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (4:6). So, I see no way that one can limit his subsequent reference to an “eternal weight of glory” to the apostles or martyrs alone.

- Hebrews’ use of Psalm 8 most definitely looks beyond the immediate political horizon. And key to my argument is the fact that Jesus came to “bring many sons to glory” so they too fulfill the psalm’s description of a humanity crowned with glory and honor, exalted above the angels, with all things subject to them. That is deification. Jesus in his humanity is the first example of the psalm’s ultimate fulfillment. But he is also the one whose blazed a trail for his brothers so they too will fulfill its description.

- Finally, it’s simply a false dichotomy to say passages are either about humanity & creation *or* martyrdom & kingdom. Throughout the Pauline corpus Paul and his co-authors freely employ the language of renewal, creation/new creation, suffering, kingdom, etc. in a lovely jumble that defies hermetically sealing them off from one another.

I am wrestling with the concept of the ressurections having metaphoric significance (I also do not understand what parameters you set, Andrew, for a “literal” resurrection of Christ. How do you see it? Was he dead and rose from a literal death by miracle? I found this study pertaining to Jewish scholarship and metaphor around Daniel 12.

@Jason Coates:

Thanks, Jason. I’ll have a look at this. I’ve taken the liberty of deleting the study from the comment and providing a link to the pdf—it’s neater, keeps the formatting, and is easier to read. I hope you don’t mind.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, I felt guilty about that too. Thanks.

@Jason Coates:

Well, here’s a partial answer to your question. The bit about the “parameters” for determining whether or not Jesus’ resurrection was understood in a literal sense is complicated. If we don’t want to go down the apologetic road of proving that it really happened, we have to ask whether the New Testament writers believed that it really happened. Perhaps key then is the argument in 1 Corinthians 15. On the one hand, Paul seems convinced that death is no longer a threat at the individual level. On the other, he thinks it’s meaningful to speculate on the nature of the resurrection body. But these are just some first thoughts.

I’ve read these posts on theosis and the comments with great interest. It’s amazing to me how a consistent historical-narrative hermeneutic — which naturaly leads to a preteristic eschatological framework — would eliminate much of these disagreements.

Let look first at the new creation aspect. When the new creation of Rom 8 and Rev 21 is put into it proper 1st century contextual category as the new people of God, the redeemed, it makes much more sense for this deification argument (based on a proper reading of Isaiah particularly ch. 65-66). I see the deification aspect in here, though likely in a different ontological aspect than Mosser (closer to the pneumatic body view that Dale Martin takes), but I also think Andrew’s eschatological framework is closer than Mosser’s (though I would disagree with the first resurrection being at the fall of Rome, I would place it at AD70 and the end of the age at the fall of the Temple).

What’s interesting is watching you two talk past each other (I don’t mean that in a bad way, I mean it sincerely — it is very interesting). A Preterist framework actually cleans a lot of this mess up IMO.

Doug Wilkinson and I are co-authoring a view in a Three Preterist Views of the Millennium, hopefully to be published sometime next year. I don’t want to hijack this post and talk about that, but I think this point is relevant. Essentially in our view we see two millennial periods in Rev 20, one of Satan and one of the saints. The one of Satan end in AD70, and the one of the saints begins in AD70 and is perpetual without end as far as the narrative concerns (particularly this is what Dan 7 has in view regarding the coming of the kingdom, and it connects with 2 Thess 1-2 where Paul saw the destruction on this little horn in his generation, for his exact audience of Thessalonians). The new heavens and earth (new covenant relationship with a new people who are raised to sit on thrones) arrived in AD70 and that’s when the Great White Throne scene commences and Hades is emptied and done away with. That’s when the “first resurrection” occurs. We don’t believe the textual variant in 20:5a has any validity (we make our arguments in our book), and it contradicts the rest of Scripture which poses only one general resurrection (John 5) after the resurrection of Christ (N.T. Wright sees that there’s only one resurrection in the NT but he doesn’t know what to do with it because of Rev 20, accepting the variant as he does), so we don’t see a second general resurrection at the so-called “end of time” (Daniel’s “time of the end” being the end of the old covenant people, Dan 9 & 12). After the general resurrection in AD70, we see ongoing judgment/resurrection at the death of each believer (Rev. 14:13).

This is important because it relates directly to the disagreements in this thread. In Andrew’s first blog on this, he says in refutation of Mosser:

“Christ and the martyrs do not reign over a “redeemed cosmos”. Kingdom is required precisely because the cosmos is not redeemed, because there is still sin and hostility. Kingdom comes to an end after the thousand year reign, when the cosmos is finally made new (Rev. 20a:6; 21:1; cf. 1 Cor. 15:24-28).”

I think Andrew is wrong here and Mosser is right. There is still sin and hostility for those living outside of the new Temple, the new H&E, in Isa 65 and Ezek 47 for example. It’s defeated for those who are inside. Even Revelation 21-22 clearly shows that during the new H&E, kings and nations are perpetually entering, and outside this new heavenly city are the immoral, the swamps and marshes of Ezek 47. The kingdom does not come to an end, the kingdom is specifically without end throughout the entire narrative . The delivering up of the kingdom to God in 1 Cor 15 is not it’s end; Paul didn’t surrender the kingdom when he delivered it to the Corinthians. This co-reigning is exactly what Rev. 21:22 & Rev. 22:1 depict.

I think the most logical option for how the early church developed its eschatology, ontology and deification schemes is our scheme of the millennium, which is inherently a type of proto-Amillennialism that would have been very at home in the early church. Clearly we see the deification of the saints in the early church especially the Eastern Orthodox Church, and you can’t have deification if Hades still exists and the New heavens and earth are the material cosmos and still awaiting renewal (some of the early writers saw this as an already reality — Eusebius quotes it in Theopany).

The Jewish hope for renewal as Andrew said wasn’t the universe as we know it in the 21st century, it was of the nation of Israel (and inclusive of the Gentiles into a new people, whether they saw it or not). This can be clearly seen in Matt. 17:11-12. Yet Peter would go on to say that heaven must receive Jesus until the restoration of all things that the prophets predicted (including Isa 65-66), and we know as Andrew and many others have shown that the Parousia of the Son of Man was in the events of AD70, as Jesus himself promised that it would happen while some of the disciples were still alive. So it becomes disjointed to belooking for a second, bigger, more “real” restoration (the known material cosmos), on top of the one the prophets and Peter looked for. I suggest this view ultimately arose due to a combination of neo-Platonism and a knee-jerk reaction against Gnosticism in the second century.

I think that the entire ontological argument of the transition of man under salvation and resurrection can only be cleanly accomplished through our scheme for the resurrection, millennium, and kingdom. To put it another way, if the EO church was right and truly established orthodoxy, then the only possible orthodox end game is the one we propose, whether they realize it or not. The only other way around that is to start pushing passages outside their exegetical context and forcing double fulfillment on some but not others, but that runs into a lot of problems. More could be said but I’ll leave it there for now.

@Jerel:

Jerel, I’m not going to respond to the substantive argument. I just find the Preterist refusal to allow that the New Testament might have something to say about Rome very peculiar. The expectation of judgment on Rome is so widespread in second temple Jewish writings that it seems perverse to discount it when it comes to the New Testament. It looks to me as though Preterists are being blindly dogmatic about it, if you’ll forgive me for saying so.

Even Revelation 21-22 clearly shows that during the new H&E, kings and nations are perpetually entering, and outside this new heavenly city are the immoral, the swamps and marshes of Ezek 47.

Did you see this post: What happens at the end of Revelation? A bit of a concession to the Preterist argument perhaps.

…we know as Andrew and many others have shown that the Parousia of the Son of Man was in the events of AD70, as Jesus himself promised that it would happen while some of the disciples were still alive.

As you know, my argument is more complex. Jesus understood his own mission to Israel in light of the Son of Man narrative, culminating in the deliverance and vindication of his disciples following judgment on Jerusalem. The church in the Greek-Roman world, I think, reoriented the Son of Man narrative towards the foreseen victory of YHWH over the pagan nations and over Rome in particular. The final judgment and renewal of creation is not dependent on the Son of Man narrative.

I suggest this view ultimately arose due to a combination of neo-Platonism and a knee-jerk reaction against Gnosticism in the second century.

Sibylline Oracles 2, probably dating from the turn of the era and not what you’d call a neo-Platonist text, predicts God’s judgment of Rome, the salvation of the pious, the rule of the Hebrews for some generations, concluding with a final destruction of the earth, resurrection, punishment of the wicked, and a new world. A very similar schema to what we find in Revelation 18-22, in my view.

@Andrew Perriman:

I just find the Preterist refusal to allow that the New Testament might have something to say about Rome very peculiar. The expectation of judgment on Rome is so widespread in second temple Jewish writings that it seems perverse to discount it when it comes to the New Testament. It looks to me as though Preterists are being blindly dogmatic about it, if you’ll forgive me for saying so.

Well you’re forgiven :) I think however you may be misunderstanding part of the preterist argument. We’re not ignoring Rome, we are just dealing with it differently than you are. I have read a lot of 2T literature and though not an expert in it by any means, I see the same thing you do. It’s easy to pick up on that in the NT narrative, how the Jews were looking for a Messiah to bring a kingdom to break the yoke of Rome. But the kingdom Jesus brought was not the kind they were looking for.

Now you’ll have to forgive me, but I don’t think you’ve dealt very adequately with the preterist arguments for the kingdom having come in AD70. I think the nature of that kingdom was quite clear that it was spiritual in nature (“within you”; “does not come with observation”; “not of this world”; etc) and that it was to happen at the end of the 2nd Temple age (“the sons of the kingdom will be cast out;” “the kingdom will be taken from you and given to another people”; etc). Daniel 2 posits not the fall of Rome, but the fall of the metal man statue. It was the entire covenantal structure of the four beasts/nations, the ones that held cover over the Old Covenant people of God, that fell all at the same time from the rock. There are many allusions to this in Matthew, ch. 21:33ff being one of them. This metal man is replaced by the new man seen in Dan. 10. One scholar who has done well showing these connections is James Jordan. Another scholar who took not a covenantal structure but a spiritual being/divine council replacement structure is Duncan McKenzie. The point is, that the NT is very clear in many places that there was one upcoming eshatological event, and it was tied to the end of the age of the Second Temple. I know you don’t want to deal with the substantive arguments, but it’s in those arguments that we see that the Harlot city is defined as Jerusalem not Rome, so however much one wants to see Rome as the harlot, she is not. She is the beast the Harlot rides on. The technical details are worth debating, because your whole structure rides on it.

I did read your post on What Happens at the End of Revelation. I saw a little bit of some preterist concessions, but I still disagreed with your end conclusion…but that’s ok, I really don’t make more of that disagreement with folks as far as fellowship goes. I’m in about 98% agreement with you compared with pretty much everyone else I fellowship with, so you’re good bed company for me ;-)

I agree with the comment that the post-AD70 Greco-Roman church reoriented the prophecies and aligned them with the fall of Rome (it was less of a fall than an old man slipping into a warm bath, but let’s call it a fall for the sake of conversation). I don’t think that reorientation makes it right, however. I’m fine with taking the text in its true historical context and seeing how we could apply it to our present situation (which is why I like a lot of your posts), but to lift it off of Jerusalem and place it on Rome 4 centuries later is unwarranted IMO (not that you are doing that, you’re more splitting it into two, some on each end, but some ANF writers did place it all on Rome).

Sibylline Oracles 2, probably dating from the turn of the era and not what you’d call a neo-Platonist text, predicts God’s judgment of Rome, the salvation of the pious, the rule of the Hebrews for some generations, concluding with a final destruction of the earth, resurrection, punishment of the wicked, and a new world. A very similar schema to what we find in Revelation 18-22, in my view.

That’s a good point, and I would like to spend more time looking into that. I’ve done less work on this than Doug Wilkinson has, so maybe he’ll comment, but from my studies I do think a strong argument was made by some scholars that the view that the earth needed destruction and renewal originated first and foremost from Gnostic writers. But all that aside, while interesting about the Sibylline Oracles, the biblical texts themselves are more germaine to the discussion and you can’t find anything in the prophets that look past AD70 (something you said recently, right?)…and I don’t see how Peter and John were addressing anything different than what they read in the prophets.

@Jerel:

While Carl doesn’t see a fundamental disagreement in your comments, I do see a very significant one. And, I think your own comment on it is telling. In the graphics you provided you clearly show that Carl’s approach assumes and requires only one resurrection. You, on the other hand, have two resurrections, though possibly subconsciously you have one of them disconnected from the main piece of art almost as if it didn’t really connect to the theology. I then noted this very interesting sentence:

“This corresponds, conveniently, to John’s “first resurrection” of the martyrs. His “second resurrection” of all the dead is actually of only marginal interest to the New Testament (Rev. 20:4-6, 12-13).“

This comment becomes all the more interesting when we recognize what the second resurrection means to your system (and all modern eschatology). The second resurrection is the resurrection of 99% of the dead of all time, which makes it by far the most important resurrection next to Christ’s personal one. But, it’s only of “marginal interest” in scripture? Another way of saying this is that scripture almost ignores the topic of the second resurrection (an assertion that should give everyone pause).

But, what if I were to prove that the only reference in all of scripture to a second resurrection is a textual variant found in one verse in Revelation? I won’t go into the Rev. 20:5a issue in too much detail because I know you’re aware of it. But, I don’t think you’ve addressed how significant it would be if that variant weren’t in the text. If it weren’t, it would (finally) cause eschatology to line up perfectly with a theosis based soteriology, which is the fundamentally orthodox approach to the topic in Christian literature. On the other hand, to leave that variant in the text would cause eschatology to be incompatible with the soteriology of the church in the first four hundred years. Is it any wonder we never had a consensus on eschatology?

@Doug Wilkinson:

Andrew,

For clarity sake, the above post should have been addressed to you in response to the first two exchanges between you and Carl. This one is as well.

I argue that there is only one direct reference in scripture to a second resurrection, which is the textual variant in Rev. 20:5a. But, even if the other verses in Rev. 20 are added to the list per your suggestion, do you think that is fair warning to the rest of the world throughout history that God is going to judge them according to their works at some future event? The rest of that warning usually comes from a vague secondary meaning given to passages that have already in some way already been fulfilled. So, 99% of the people who will ever be resurrected for judgment will have had no unambiguous notice of it. That’s just not God’s style according to the rest of scripture.

Also, you were clear in the original post (which is consistent with your previous work) that your eschatology is heavily anchored in a political kingdom of some kind. And, you’ve said in the past that the collapse of Christendom (the European church) is an indication of the end of the kingdom era that began in the early church. A major part of your ministry as I understand it is to try to find a way of explaining the church’s role in the world after this kingdom has ended. Since Rev. 22:5 and Daniel 7:21-27 clearly argue that the kingdom will last “forever, forever and ever”, doesn’t that directly invalidate your definition of the kingdom? Since Carl, Jerel, and others are arguing for a spiritual kingdom that is continuing, and growing, even after the collapse of the European church, wouldn’t their defintion be sustained?

Recent comments