A major part of my general argument is that the modern church thinks of the New Testament as theology (or beliefs) set in a historical context and thinks that the historical context is of much less importance than the theology. My contention is that the New Testament gives us the opposite: history set in theological context, or theologically interpreted history; and that the history is of central importance. The defectiveness of our common understanding of the New Testament can be illustrated rather well by means of a couple of diagrams from Donald Hagner’s book The New Testament: A Historical and Theological Introduction.

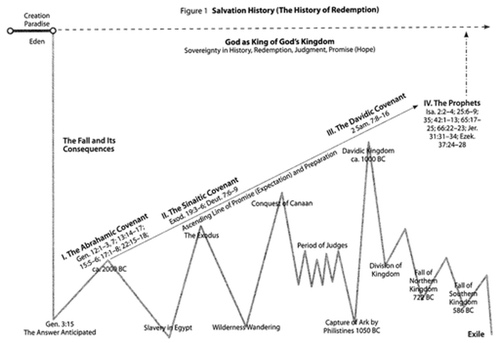

The first diagram presents the salvation-historical timeline of the Old Testament (15). We begin, naturally, with Eden and the fall, and then the chart splits between the up-and-down historical experience of Israel and an idealized trajectory which culminates in prophetic visions of a renewed creation that transcends history.

I think there are some problems with the chart. For example, I disagree with the popular argument that the answer to the fall is anticipated in the statement in Genesis 3:15 about enmity between the descendants of the serpent and the descendants of the woman. There are narratives beyond the exile that are of considerable importance for the New Testament which should be included, notably Daniel’s account of the crisis provoked by Antiochus Epiphanes. Lastly, the prophets do not envisage a return to paradise. They address what is going on in the lower part of the chart—the fall of the northern kingdom, the fall of the southern kingdom, the exile, the return from exile, and subsequent events. I will argue in my next post that this apparent language of transcendence has new creation in view only in a metaphorical sense. There is an ascending trajectory, but it does not escape the gravitational pull of history in the Old Testament. It climaxes in the rule of YHWH over the nations following the decisive restoration of his people—that is, in the kingdom of God.

But it’s the contrast between this detailed diagrammatic summary of the Old Testament story of kingdom and the simplistic chart which Hagner uses to explain Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom of God (75) that I think is really telling.

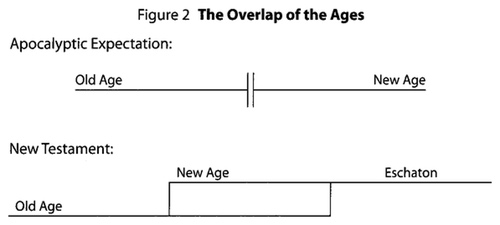

When we get to the New Testament, history has disappeared and has been replaced by an enervated eschatological schema. The clear assumption is that the historical narrative of the people of God no longer counts for anything. All we need is a flimsy two-age structure in which nothing happens any more. It’s just the church waiting for the eschaton, for ever and ever, amen.

The destruction of Jerusalem and the temple by the Romans and the conversion of the empire were much bigger historical and theological events than anything that happened in the Old Testament. The New Testament is no different from the Old Testament in that it narrates both past events and future events. Just as the Old Testament foresaw the exile, the return from exile, the defeat of Hellenism, so the New Testament foresees judgment on Israel and the overthrow of classical paganism. The New Testament chart should look like the Old Testament chart—a series of decisive events, moving into the future, interpreted theologically, culminating in the historical event of the coming of God’s reign over the nations—and whatever comes next—with the new heavens and new earth way off in the distance.

That’s where charts’ll get ya.

http://digitalsojourner.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/revelation_chart.gif

That one even shows where Satan is thrown out of Heaven (spoilter alert: it’s in the future).

Point well made. But there’s no history in it, is there.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hmm. What do you call historical fiction that’s set in the future?

Biblical prophecy/apocalyptic leaves no real doubt about what historical event or what sort of historical event is being described. Your linked chart, as far as it goes, is pure abstraction. Eschatological fiction rather than science fiction?

LOL!

The sad truth of the matter though is that graph is where 95% of (western) Christianity is at….what they believe as (Biblical) truth.

@Rich:

Yes Rich, that ‘Figure 2 The Overlap of the Ages’ would make more sense read as…

Old Age – Eschaton – New Age

It was the 40yr (a biblical generation) “eschaton” that overlapped one covenant to the next, Old to New. IOW… the eschaton was relative to the ending of the old covenant age. The new covenant age knows no end i.e., it has no eschaton.

The bible speaks of “the time of the end” NOT “the end of time”.

@davo:

davo,

my laugh was in regard to the link/graphic posted by Phil, but I agree completely with your assessment of the graph #2 in Andrew’s article.

The correct graphic, which you laid out, is presented in Gal. 4:21-31. I find it amazing how people miss such as basic thing and, which of course, takes them down a completely wrong understanding of NT eschatology when they don’t see it. ie. Andrew’s fixation on Rome’s fall.

@Rich:

Ah yes… Phil’s diagram link above was to one of the countless imaginative charts invented by dispensationalist Clarence Larkin.

@davo:

Mine was from Ironside, but I like Larkin’s better. I especially like how the church gets raptured off the earth, then comes back to the earth for the millennial kingdom, then leaves the earth again while it’s renovated by fire, then comes back.

They say you get harps in heaven, but it’s really a bungee cord.

“Ironside”… my bad, I stand corrected. I found it on a pictorial link to Larkin’s work etc.

“harps in heaven” – yep that pretty much goes along with the notion Christendom has presented of God being a divine magician-come-Santa Clause. *_*

@davo:

I hadn’t heard of Larkin until I followed your link, but his charts blow Ironside out of the water. So much more complicated and more text and pictures packed into that space. I’m definitely using him from here on out for eschatology jokes.

but it’s really a bungee cord.

LOL….now that was funny!

On a slightly more serious note, I remember that last diagram from Geerhardus Vos. I don’t know if I originated with him, but the point is the same: you have the present evil age (kosmos) and the age to come (eschaton), and the ages overlap between the first and second comings of Jesus with the eschaton being a current spiritual reality, but not a consummate one.

This schema more less defines the “boxes” for people to put prophecy in. A prophecy is either about the first coming of Jesus or the consumation of the eschaton. There is nowhere else for them to go. It’s either the incarnation or the end of time, and maybe you’ll get a little bit touching on the destruction of Jerusalem, but even those little hiccups roll up under the end of the kosmos. It’s as if an earthly deliverance is intrinsically inferior to a spiritual one.

This is a very anemic sort of eschatology that has the practical effect of abandoning hope for this world to wait for the eschaton. We’re all just polishing brass on the Titanic, saving as many souls as we can until the time is up.

I much prefer an eschatology that takes seriously the deliverance and judgement of God in history and invites me to be an active participant now in the new creation.

Re the overlap of the ages, I think you make a good point in that history (temple-destruction, Rome) is insufficiently represented. But there is in my opinion far more happening in this (‘overlap’) scheme than in the narrative-historical, where the narrative seems to run out of steam after the supposed ‘conversion’ of the Roman Empire.

The kingdom is breaking in constantly into history in the ‘overlap’ period (between Old Age and New Age/Age to Come). The church isn’t waiting in an enervated state for the eschaton (for ever and ever amen), though that may be the impression given by some of its members.

Around the world, the church is constantly being renewed and impacting history. It is, in effect, a ‘counter-history’, through which a kingdom is introduced which runs on its own principles, and poses a constant challenge to other kingdoms and empires. Even today, this can be seen in the various political hot-spots of the world, though not always in evidence in the news media.

I don’t go for Donald Hegner’s diagrams though, and I do think it oversimplifies OT history especially.

@peter:

As you know, my argument is that the apocalyptic narrative of New Testament eschatology runs as far the predicted defeat of pagan Rome and the conversion of the nations of the empire to the worship of the God of Israel. John interposes a “thousand year” period between this climactic event and a final judgment and renewal of heaven and earth. The New Testament does not attempt to predict what will happen in this thousand year period, but I agree, subsequent historical events are no less part of the theologically interpreted narrative of God’s people: the Great Schism, the Reformation, the clash with Islam, the Enlightenment, missionary expansion beyond Europe, the collapse of Christendom, postmodernity….

Hi!

Is there any chance you have figure 1 in higher resolution? I LOVE the diagram and have been looking for it everywhere!

are you able to send me a copy?

Recent comments