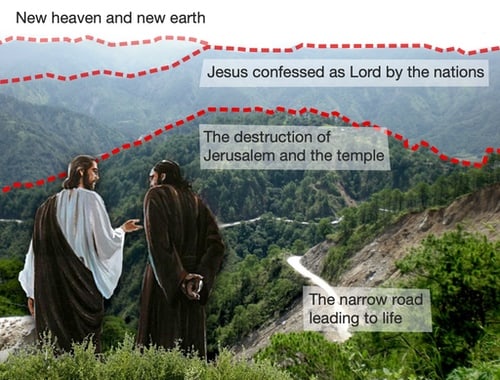

The New Testament narrative at every point is directed towards future events, from John the Baptist’s announcement that the bad trees of Israel would be cut down and burned in the fire to John the Seer’s vision of a new heaven and a new earth. I say “events”—plural—because I don’t think the standard modern eschatological assumption that we are still waiting for a single “end” makes sense historically. I argue instead for a three horizons model that fits the evident historical contours of the New Testament without sacrificing the conviction that God will have the final word.

If we imagine ourselves standing with Jesus and his followers on the high mountain of prophetic foresight—to begin with, quite literally on the Mount of Olives—what looms first in our field of view is the grim prospect of a devastating war against Rome. Jesus’ message to his people was that they were on a broad road leading to the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and the massive loss of life represented symbolically by Gehenna. This is the first horizon, the future as Jesus saw it. He called the Jews to repent of their folly and challenged some of them to follow him down a narrow road of suffering that would lead to the life of the age to come.

The disciples hadn’t gone too far down this difficult road before they realised that the historical salvation of the people of God would have far-reaching repercussions for the nations of the Greek-Roman world. Paul summed it up precisely when, according to Luke, he told the men of Athens that the creator God of Israel was no longer prepared to overlook their ignorance and had “fixed a day on which he will judge the empire (oikoumenē) in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed, giving assurance to all, having raised him from the dead” (Acts. 17:31, my translation).

This gives us our second “eschatological” horizon—somewhat hazier from where the apostles stood, harder to discern in detail—when YHWH would judge the ancient pagan world, and his Son would be acclaimed as Lord by the nations. Historically speaking, this was the conversion of Rome and the beginning of European Christendom. I’ll get on to defending that contentious claim in a moment.

Then in the furthest distance the early church could just about make out a third horizon of the final putting right of all things—a final judgment of all the dead, the elimination of all evil, the destruction of death, and the remaking of heaven and earth. This third horizon is much more important to us now, not least because we are facing a global ecological crisis that overrides national, cultural and religious distinctions. But the outlook of the church in the first century was geo-politically circumscribed. No one was worried and climate change.

Now, obviously, the most controversial part of this hermeneutical model is the suggestion that the conversion of the Roman Empire from paganism to Christianity constituted anything close to a “fulfilment” of New Testament expectations regarding the “day of Christ”. One response to my argument about the new Jerusalem in Revelation 21:22-26 was that Christian Europe was at best an opportunity for the church to be the New Jerusalem community but the church blew it: ‘I can only see that opportunity wrongly seized by the church and enacted in ways scarcely different from “Babylon”’.

The problem is that the traditional “single end” model (setting aside all the dispensationalist elaborations) has left us with the impression that everything that we would associate with the final renewal of creation (destruction of sin, Satan and death) is already entailed in the parousia. We’ve had no reason to differentiate. But if we examine the passages that describe the day of our Lord Jesus Christ, we find that much less happens than we might have expected. It’s a point I’ve made many times: the kingdom of God is not new creation.

So here’s the question: what did the early church think would actually happen on the day of Christ?

1. The revelation of his presence

The eschatological moment, the day of Christ, is conceived as a revelation (apokalypsin) or “appearing” (1 Tim. 6:14; 2 Tim. 4:1; Tit. 2:13) of the Lord Jesus (1 Cor. 1:7), an “appearing of his royal presence” (tēi epiphaneiai tēs parousias: 2 Thess. 2:8), as simply his parousia (1 Cor. 15:23; 1 Thess. 2:19; 3:13; 5:23; 2 Thess. 2:1; 2 Pet. 1:16; 3:4; 1 Jn. 2:28). Paul describes a descent of the Lord from heaven in language which strongly evokes Old Testament theophanic visions (“with a cry of command, with the voice of an archangel, and with the sound of the trumpet of God” (1 Thess. 4:16). The church prayed that the Lord will Jesus would “come” and bring about the foreseen transformation (1 Cor. 16:22; Rev. 22:20).

To what extent this appearing or revelation or descent or coming was imagined in “literal” terms is difficult to say, but the character of such apocalyptic discourse certainly leaves open the possibility that this is symbolic language for something that would transpire on the plane of human history.

2. The end of persecution and punishment of enemies

Persecution would come to an end and the persecutors would be punished by God. The clearest statement of this is found in 2 Thessalonians 1:5-10. The believers were having to endure intense suffering for the sake of the future kingdom of God. Jesus would be revealed from heaven, the persecution would end, and their opponents would “suffer the punishment of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord”—that is, they would be excluded from the new political-religious order and, before long, will become a thing of the past.

3. The resurrection of the martyrs

Those who had died in Christ, perhaps specifically as martyrs, would be raised. This is Paul’s improvised apocalyptic argument in 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17 (cf. 1 Cor. 15:23). The Lord would descend from heaven, like a warrior king coming to be welcomed by the citizens of a remote provincial city. The narrative is left incomplete, but probably we are to think that he would then return to his place of rule in heaven with the resurrected dead and perhaps with the transformed church.

According to John, the martyrs would be raised, following the overthrow of corrupt idolatrous Rome and the confinement of Satan to the abyss, and would reign with Christ for a thousand years (Rev. 20:4-6). In the symbolic landscape of John’s vision this is envisaged as a reign on earth, in the aftermath of the defeat of the beast and the kings of the earth (Rev. 19:19-21), but I suggest that what John saw, when heaven was “opened” (Rev. 19:11), was an apocalyptic representation of the reign of the exalted Christ at the right hand of God in a new post-pagan world. The reign of Christ presupposes the continued existence of enemies (cf. 1 Cor. 15:25-28) and therefore the continuation of history. We have not yet reached a final end.

4. The vindication of the apostles and the faithful witnessing churches

Salvation was not so much something that the churches had because they believed in Jesus; it was something that they would have if they weathered the storms of persecution to stand blameless before the throne of Christ at his parousia. Paul told the Thessalonian believers that if they overcame opposition by putting on the armour of faith, etc., they would obtain salvation on the day of the Lord and whether they were alive or dead, would live with him (1 Thess. 5:8-10; cf. Rom. 13:11-14; Phil. 1:6, 10). The writer to the Hebrews urged his readers to be “imitators of those who through faith and patience inherit the promises” (Heb. 6:12). The marriage supper of the Lamb is perhaps the supreme vision of the vindication of the suffering churches, whose faithful witness eventually leads to the desolation of Babylon the great (Rev. 19:6-9).

Of the apostles specifically Paul wrote: “we all must appear before the tribunal of Christ in order that each may receive the things for what he did through the body, whether good or substandard (phaulon)” (2 Cor. 5:10, my translation; cf. 1 Cor. 3:14-15; Phil. 2:16). The task of the apostles was to establish and form churches which would bear consistent witness, with moral and spiritual integrity, to the coming day of Christ and its implications for the ancient world.

5. The end of classical paganism

There would be a judgment of the unrighteous pagan religious system that had dominated Israel’s world for centuries. I have mentioned already Paul’s clear and unequivocal declaration of such an outcome in Athens. It is the “wrath” that was coming on the ancient world, against the Jew first, then against the Greek, from which the churches would be delivered because of their faith in Jesus as Lord (cf. 1 Thess. 1:9-10; Rom. 1:18; 2:6-10; Eph. 2:3; Col. 3:6; Heb. 9:28; 2 Pet. 3:7; Rev. 11:18).

6. The overthrow of Rome

It would also be a judgment of the aggressive political powers that had forced matters to an eschatological tipping point. The Lord Jesus would destroy the blasphemous Caesar-figure, the man of lawlessness, who made himself out to be a god, by the “appearance of his presence” (tēi epiphaneiai tēs parousias). John put forward a comprehensive vision of the judgment and overthrow of “Babylon the great” and the Satanic powers that inspired its antipathy towards YHWH and his people (Rev. 17-19).

7. The rule of the Lord Jesus Christ over the nations

The climax to the hymnic piece about Jesus in Philippians 2:6-11 is not that he had been exalted but that eventually the nations would confess him as Lord and that, as a result, the God of Israel would be glorified across the empire. The prophetic paradigm for this triumph is found in Isaiah 45:20-25. When YHWH acted to redeem his people and restore them, it would become apparent to the pagan nations that there was no other god; they would abandon their idols, bow the knee to YHWH and confess that he alone was God.

Jesus was the root of Jesse who would arise to rule the nations (Rom. 15:12; cf. Is. 11:10). Psalms 2 and 110 are widely applied. Jesus was the king of Davidic descent who had been seated at the right hand of God and given the nations as his heritage to rule with a rod of iron (cf. Rom. 1:3-4; Heb. 1:13; Rev. 19:15). He was “the firstborn of the dead, and the ruler of kings on earth”; he would be “King of kings and Lord of lords” (Rev. 1:5).

8. The foundation of the new Jerusalem

Finally, I’m inclined to think that in Revelation 21:9-22:5 we are given a highly symbolic depiction, drawing especially on Ezekiel’s vision of the restored Jerusalem in the midst of the nations, of the presence of God in the world after the overthrow of pagan Rome. If this is correct, and it is not a reiteration of the descent of the holy city in Revelation 21:1-8, this is the only place where the New Testament attempts to describe how things would be after the establishment of Christ’s reign over the nations.

The city of God’s presence would displace Rome as the centre of an idolatrous, and depraved civilisation. In it the servants of God would serve as priests in the presence of God and the Lamb. The kings of the nations would actively acknowledge the glory of God by bringing their wealth into the city, but no vestige of the old pagan order would be allowed in. The nations, so brutalised and damaged by Roman imperialism, would be healed by the leaves of the trees that grow along the banks of the river that flows from the city. The presence of the living God generates a whole new moral order.

Less is sometimes more

So the focus of the parousia motif—the day of Christ—is almost entirely on the victory of the suffering church over hostile paganism. Its scope is really quite limited. The long period of persecution is brought to an end, the supernatural and worldly opponents of YHWH are defeated, the nations confess Jesus as Lord to the glory of the one true living God, worship of the old Greek and Roman gods is progressively abandoned, and a new political-religious order is established, with a radically different set of values, in which Jesus rules with the martyrs. All this happened in due course.

Nothing suggests that this new order would constitute a perfect or ideal state, or that the church would get everything right. We’ve over-interpreted it. At the heart of the vision is the simple conviction that the nations as nations—and not just the churches as prophetic communities—would worship one God and acclaim one Lord (cf. 1 Cor. 8:5-6). The vision remains true to the fundamental historical realism of biblical prophecy: the old age of classical pagan hegemony is brought to an end, a new age of Christian hegemony is introduced. History continues. And continues. And now the age of European Christendom in its turn has come to a slow and inglorious end, and the church is having to devise a new modus operandi.

Your “three horizions model”, the way you describe it here, seems quite compelling.

N.B. The older post that you link to, in the first paragraph, as “three horizions model” (but is, in fact, titled The Son of Man sayings and the horizons of New Testament eschatology — 13 February, 2016) speaks, at best, of only two of those “horizons”.

So, let’s take stock:

- The “first horizon” (destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple) is in the past and gone in 70 CE, at the very latest in 135 CE.

- The “second horizon” (Jesus confessed as Lord by the nations), “[h]istorically speaking, … was the conversion of Rome and the beginning of European Christendom”. This was presumably achieved with the official conversion of the Roman Empire, let’s say by 400 CE, and lasted up to the French Revolution (1789 CE).

- As for the “third horizon” (new heaven and new earth), now that “the age of European Christendom in its turn has come to a slow and inglorious end”, it should be, inevitably, the next on the agenda.

Logic would dictate, if we take the above model seriously, that the present time is NOT the time when the Church (what remains thereof) helps establish the Kingdom of God, BUT only a time when we wait for God to bring it about Himself.

Thank you. Some clarifications:

1. The three horizons model is an attempt to explain how things appeared from the perspective of Jesus and the New Testament church. They foresaw the confession of Jesus as Lord by the nations. They did not foresee the French Revolution and the triumph of secular humanism (unless Revelation 20:7-10 somehow registers this possibility). I would count this “disaster” as an eschatological or prophetic horizon on the same scale as the exile, the destruction of Jerusalem, and the conversion of Rome.

2. We might then also begin to imagine that another horizon is beginning to emerge from the mist—perhaps a global environmental crisis. It’s the way history goes. I agree that the prospect of a new heaven and new earth should be on the agenda, and perhaps it has a special relevance at this time. But I think the lesson of scripture is that there are always intervening historical developments and crises that impinge on the integrity and witness of the people of God. We do history in the light of the final vindication of the living creator God.

3. I think that the “kingdom of God” language belongs to history and should not be used for the final renewal of creation. It has reference to how God safeguards, judges, reforms and renews in the course of history, in response to historical events of great magnitude—such as the collapse of Western Christendom, though, as I say, this “kingdom” event was beyond the horizon of the New Testament church.

This is one of the ways, incidentally, in which the narrative-historical approach can inform, give direction to, the church today.

@Andrew Perriman:

1. My mention of the date of the beginning of the French Revolution doesn’t mean that it could be located in time from the perspective of Jesus and the New Testament church. Nor could the “conversion of Rome and the beginning of European Christendom” be put a precise data on, from the same perspective, BTW. Nor could even the date for the disaster of the destruction of Jesusalem and its temple be located precisely in time. Even today, 70 CE is a conventional date. There were two more Jewish-Roman wars, after that date, and only 135 CE can be considered, with some reason, a definitive final date. So the dates I have indicated are obvioulsy and legitimately given from our historical-theological persective. Now, 21st century.

2. The emergence of a “global environmental crisis” (there are, and/or have been several others BTW: nuclear crisis, overpopulation crisis, migration crisis, at present, etc.), while it is most serious and requires acting, rather than sitting on our hands, is a false “horizon”. Once we have become collectively secularized, our only “religion” left is “progress”. I believe that Solovyov’s book Three discussions. War, progress, and the end of history, including a short story of the Anti-Christ (1900/1904) is much more helpful for our understanding than any immediately contemporary perspective (see also my Solovyov’s Antichrist).

I think that the “kingdom of God” language belongs to history and should not be used for the final renewal of creation. It has reference to how God safeguards, judges, reforms and renews in the course of history, in response to historical events of great magnitude—such as the collapse of Western Christendom, though, as I say, this “kingdom” event was beyond the horizon of the New Testament church.

3. The “kingdom of God” notion was certainly the centre of Jesus’ preaching (and before him of John the Baptist’s). While it is still perfectly valid for today, It has nothing to do with the action of the church . In your linked post of 7 March, 2018, you write :

6. The kingdom of God was something that God would do eventually

It still is.

Recent comments