What took us so long? G.B. Caird on the historical Jesus

I was pointed to G.B. Caird’s Ethel M. Wood Lecture “Jesus and the Jewish Nation” last week. The lecture was delivered in 1965 and published by The Athlone Press. It can be downloaded from Rob Bradshaw’s BiblicalStudies.org.uk.

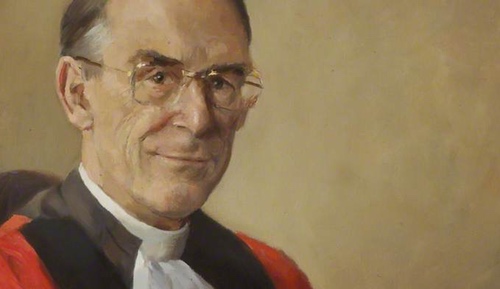

I tend to trace my understanding of Jesus’ eschatology back to Wright’s Jesus and the Victory of God, which was published in 1996. But Caird’s lecture gives us a brilliant, vivid, precise and very accessible sketch of the reading, in much the same language, from thirty years earlier. Wright acknowledges the influence of Caird—“it was his little book Jesus and the Jewish Nation that provided the clue to a fresh line of thought” (JVG xix). But still, you have to wonder why it has taken us so long.

Recent comments