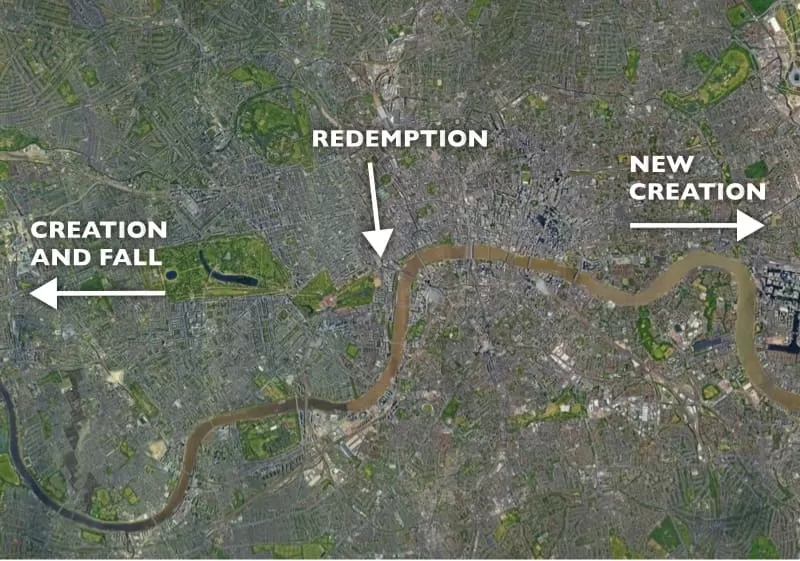

In an article on the Gospel Coalition website, adapted from a book about evangelism, Matt Smethurst attempts to explain the gospel. He suggests, to begin with, that we can view the gospel from two perspectives: a high level or aerial view, which reveals to us the overall shape of the biblical narrative; and a street level view, which “fleshes out how this epic narrative becomes good news for sinners like us.” He draws an analogy with two different views of a city, one from flying over in an aircraft, the other from walking the streets.

That’s a good hermeneutical model at first glance, but it’s not difficult to find fault with it.

First, we appear to be so far above the city that we can make out very little except the outer boundaries (creation and fall on the one side, new creation on the other) and some sort of large public space—a main square, perhaps—in the middle (redemption). The rest of it is just featureless urban sprawl. What would hard-working city planners make of that account?

Secondly, street-level experiences vary greatly, depending on where we are walking in the city—in some drug-blighted, inner city gangland, in the shiny new developments around the docks, in a park with its flowerbeds and ornamental fountains, among the towering office blocks downtown, in an immigrant community, in the leafy middle class suburbs, and so on. Perhaps many people in the city never get anywhere near that large central square. Maybe it’s full of tourists.

In other words, the model is reductive in both directions. Everything between the cosmic and the personal gets ignored.

We are then presented with one of those alliterative and formulaic outlines of the gospel so beloved of evangelicals, which Smethurst thinks synthesises the best of both perspectives: the Ruler, the Revolt, the Rescue, and the Response. I won’t summarise the stages of his argument—you should read the article; but I will comment on it, a little disjointedly, in the hope of showing why it is a poor account of “gospel” as a biblical concept.

The Ruler

I presume we start with “Ruler” for the sake of the alliteration. The God of Genesis 1 is presented not as a ruler but as the living God who created and declared good. The only ruler in the chapter is humankind, which is instructed to subdue the earth and have dominion over all living creatures. The creator has no need to subdue what he has created or exercise dominion over living creatures in order to feed and defend himself.

This God is not an “eternal community” of three persons, who has instilled love “at the heart of the universe.” Love doesn’t come into the story until we get to the patriarchs, to whom God shows “steadfast love” in keeping with the promise made to Abraham. Outside of John’s Gospel, it is hard to think of anywhere in scripture that speaks of the love of God for humanity in general, not just for his own people. Perhaps someone will correct me on this.

Nor did God make humanity in their image “to know and enjoy his love.” The most we can infer is that humans were made in the image and after the likeness of God with a view to their not being like the living creatures which had been created “according to their kinds.” Where do we get the idea from that the “chief end of man” is to glorify God and enjoy him forever?

The Revolt

Sin is characterised in very modern terms as a failure of love: we “look for love in all the wrong places because something has gone terribly wrong in our hearts.” Perhaps it’s necessary to pander to an insecure and self-absorbed generation, but even now there are larger narratives at work which suggest that sin should be understood, in the first place, as a repudiation of the creator. Isn’t the fundamental and systemic “sin” of the culture we inhabit its functional atheism? Everything else derives from that, including our distorted loves. At least, that would appear to be Paul’s argument in Romans 1:18-32.

Adam and Eve turned their backs on God, Smethurst says, “fracturing his creation and plunging his image-bearers into an ocean of sin.” This is not what the Bible says. Creation is not changed by the fall other than that the man and the woman become subject to death. Otherwise, they are merely expelled from a safe garden into a world that was presumably always unsafe, and they suffer the consequences.

The nature of sin

The commonplace argument that sin “is more relational than behavioural” applies to Israel and the church because God’s people have a relationship, which can be broken. In Smethurst’s account, sin is fundamentally individualistic and generalised because he is thinking like a modern evangelical, but he draws on texts that have a necessary corporate dimension. Most of the sin in the Bible is committed by God’s people and has corporate consequences.

For example, Smethurst quotes Isaiah 59:2 as though it referred to all people: “your iniquities have made a separation between you and your God” (Is. 59:2). But this is addressed to Israel; it is God’s people who have sinned, in many personal and societal ways, and need to be saved. The story in progress here should not be ignored.

Even the parable of the prodigal son is a story about division in Israel, not about the broken relationship between the individual sinner and God. When the son returns home and says, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you” (Lk. 15:21), he differentiates between God (“against heaven”) and Abraham as the father of Israel (“before you”). The son’s reckless and selfish behaviour is no less part of Israel’s problem than his brother’s self-righteousness, but the younger son repents and is restored to the historic community of God’s people.

If the church is to have any credibility as an interpreter of the Bible, we have to get beyond the trivialising idea that the Bible is an overblown communication from God to the individual sinner. It is the dense, complex account of the long history of a people, from the call of Abraham out of the shadow of Babel to the overthrow of Babylon the great, which was Rome.

That’s the story that defines Jesus—the Son sent at the right moment in history (on this see my recent CBQ article), before it was too late, to redeem those under the Jewish law from the consequences of their sins (cf. Gal. 4:4).

Children of wrath

Smethurst points to the impossibly high bar of “moral perfection” and brandishes the threat of a “hopeless future in hell”. So if you want to go to heaven, you have to be perfect, for “Only persons whom God considers perfect can live with him forever.”

Ephesians 2:1-3 is introduced as evidence that all people are dead in their sins and “by nature children of wrath.” This passage needs to be read carefully:

And you were dead in the trespasses and sins in which you once walked, following the course of this world, following the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience—among whom we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. (Eph. 2:1–3 ESV)

Paul first addresses the Gentile Ephesians: they were dead, etc., following the prince of the power of the air. Gentile culture is under the power of a supreme anti-Godly “spirit” which is now at work even in the “sons of disobedience”. What he means is that rebellious Israel (“sons of disobedience”) is now inspired by the same demonic force as the pagan nations and, therefore, faces destruction.

This is why he now switches to the first person plural: “among whom we apostles—or perhaps more broadly we believing Jews—also lived in the passions of our flesh,” etc. He is presumably thinking of his own fanatical opposition to the purposes of God. So we apostles or Jewish believers were “by nature children of wrath,” subject to the coming judgment against Israel, “like the rest” (hōs kai hoi loipoi). He doesn’t say “like the rest of mankind,” so I think it more likely that he differentiates here between those Jewish believers on whose behalf he speaks and the rest of his people.

Again, I stress the point that “wrath” in the Bible is directed against people groups—Israel, in the first place, then the nations which oppose Israel. And “hell” is not a biblical concept.

Now, however, Jews and Gentiles together have been saved by the grace of God. But nothing is said about going to heaven. They have been made alive in order to be a community that manifests the “immeasurable riches of his grace” in the coming ages of human history and performs the good works for which they have been recreated in Christ Jesus (Eph. 2:4-10).

The immediate significance of Jesus’ death in this argument is that it removed the barrier of the Jewish Law, which divided Jews and Gentiles (Eph. 2:14-16). This is not a death for the personal sins of all people. It is a death for the structural problem of ethnic division, so that non-Jews might be incorporated into the people of God and that God might be seen to be God not of the Jews only but also of the Gentiles (Rom. 3:29).

So what salvation meant for Greeks in Ephesus was that they became part of a people from which they had previously been excluded. By extension, salvation today means to become part of a community that two thousand years ago was redeemed, reconciled to God, and reconfigured with dramatic historical effect.

God’s “solution” to the problem

We are always in too much of a hurry to get from the expulsion of Adam and Even from the garden to Jesus, and in our haste we miss the real solution to the problem of sin and the relative significance of the cross.

The divine response to the degeneration of created humanity is not Jesus but Abraham, who is the beginning of a new creation family which will serve God as a priestly society or nation in the midst of all the peoples of the earth.

But what has immediately triggered this response is not the seminal disobedience of Adam and Eve but the civilisational hubris of the builders of Babel. It is the whole city that matters now, not the outer boundaries, and we should expect the solution to operate on the same level. The solution is counter-civilisational.

The localised priestly society, however, fails to bear consistent witness to the living God, gets into trouble, and then needs saving. The large main square is not a stopover between the outer limits of creation and new creation. It is the integral hub of a bustling metropolis that is being extended even now. Salvation is not merely relational. It is not merely corporate. It is historical. In the fulness of time, at a critical moment in the history of Israel, God sent out his Son….

And that means that the good news is also relational, corporate, and historical. When God acts to redeem and restore his people at whatever moment in history, that is good news. When he does something that impinges on the religious and social life of the cultures, societies, civilisations in which his people are embedded, that is good news and should be proclaimed as such.

So, in a nutshell, what Jesus does is not save humanity; he saves the solution, and this has far-reaching eschatological consequences. For a while, at least, it turns the relation between God’s people and the nations upside down; they become the head and not the tail (cf. Deut. 28:13).

The Rescue

To be fair, Smethurst acknowledges that Jesus appeared after “centuries of rebellion by God’s people,” but to couch this as the “second person of the eternal Trinity” becoming a man is hardly Pauline thought.

It is also misleading, I think, to say that “Jesus lived the life of moral perfection that Adam failed to live, that Israel failed to live, and that you and I have failed to live.” The New Testament does not portray Jesus’ obedience in universal ethical terms: he is obedient insofar as he faithfully pursued his vocation. When he is tested, as in the wilderness, it is not his moral character that is put under pressure but his mission. The writer to the Hebrews even says that Jesus, despite being a son, “learned obedience” through his suffering and in that way was “made perfect” (teleiōtheis).

Jesus is not the ideal human person; he is affirmed by God not as a morally perfect individual but as the “son” or “servant,” who has been anointed with the Spirit to carry out God’s purpose (Mk. 1:10-11).

It’s more or less correct to say that Jesus “died in the place of the law breakers,” and I think there is some point to the claim that he died as a penal substitution for the sins of his people: it is at least symbolically significant that he died in the place of the insurrectionist Barabbas. It makes no sense, however, to say that he was punished for the sins of the Gentiles.

Smethurst’s convoluted argument about winning 82 NBA games in a season strikes me as specious. The point of justification in Paul is not that believers are granted an absolute moral perfection. It is much more narrowly that they will be justified or vindicated for their belief in the lordship of Jesus when he is eventually confessed as lord by the nations.

Justification has to do with being on the right side of history. When it comes to moral behaviour, we are expected to act righteously and we will be judged accordingly.

The Response

So the question for the non-believer to ask is not “What must I do to be right with God?” but “What must I do to be part of the people of God?”

The existence of a new creation, priestly people through history—at least from the call of Abraham to the overthrow of pagan Rome—is what the Bible is all about. Assuming that this story continues even after the collapse of Christendom, the good news must remain relational, corporate, and historical. That has all sorts of personal implications, including the life-changing incorporation of individuals into a community in which the Spirit of the living creator God dwells. That will certainly demand repentance, faith, worship, and a radical reorientation of life along the axis of the biblical story.

But if there is “good news” in biblical terms to be proclaimed, it ought to be about the much larger action of God in and through his people at this moment in history. Do we have something to be excited about? If not, well….

The paragraph, ‘God’s “solution” to the problem” is a particularly clear way of framing the big story and what Jesus role is. The standard evangelical line is one so stubbornly embedded in my way of thinking, it seems to survive in another dimension unmoved by any amount of new incoming data. This little paragraph has helped pierce deeper into that unconcious dimension of religious belief. If that makes any sense. That simple resetting the problem-solution dynamic into Abraham’s context to reframe the context into which Jesus joins in seemed to click in a new way. Thank you.

There are two areas I’m exploring right now, and I think this post begins to address both of them:

- I’ve been trying to better “feel” what a community-focus vs individualistic-focus is like, especially in how we interpret the Bible. A few of your recent posts have stretched my understanding here.

- I’ve become more aware of a hyper-focus on morality.

It feels like modern Christianity

- Views sin solely as moral blemishes

- Salvation as correcting those moral problems

To me this feels little better (though slightly different) than works legalism: we are still fixated on what “we do.” Your comment “They have been made alive in order to be a community that manifests the “immeasurable riches of his grace” in the coming ages of human history and performs the good works for which they have been recreated in Christ Jesus” (for me) points to something different than salvation as moral perfection before God.

I also read your comment on the law as a critique of the modern notion that the law was about trying to correct humans’ morality.

I’m just starting to focus on our morality fixation, just wondering if you agree with my half-baked swirls of thought, or have any more thinking on this subject?

@Kevin:

Hi, Kevin. Here’s a quick response. See what you make of it.

The point I always try to get across is that New Testament thought, as an extension of Old Testament thought, operates historically or diachronically, not statically or synchronically. So all New Testament ideas (sin, gospel, salvation, justification, witness, evangelism, etc.) have an eschatological orientation; they have in view the unfolding of tumultuous and transformative future events.

Morality is certainly part of this, but it flows, of course, from theological error: the Jews turn their backs on YHWH and act unrighteously; the Greeks worship the creature rather than the creator and are handed over to sexual perversion and social evil.

Paul’s conviction is that this will mean “wrath,” first against the Jew, then against the Greek; and wrath in scripture, as I said, is always a historical phenomenon: so in this case, judgment against Jerusalem, judgment against Athens or Rome and the political-religious systems which they sustain.

Salvation also has these outcomes in view. In the first place, something needs to be salvaged from the train wreck which is first century Israel, and it turned out that Jesus’ life and death were used by YHWH to renew his people and make them fit for what was to come.

Secondly, Greeks were “saved” by abandoning their idol-worship and becoming part of this redeemed community of “Israel.”

This community of Jews and Greeks, united by the Spirit and their belief that Jesus would inherit the nations, then has to function as a prophetic sign, a pointer to the foreseen eschatological climax to the story: the worship of Israel’s God by the nations and the confession of his Son as “my Lord and my God” rather than the blasphemous Caesar.

But to be a legitimate sign the community has to live and behave accordingly: as one people, who keep the law written on their hearts, confessing Jesus as Lord, worshipping the one true God, etc. They have to embody—actually quite strictly—the ideals of the life of the age to come in their corporate existence in the present, under very difficult circumstances.

It seems to me, finally, that the church in the West is going through a similar process now, only without the prophetic clarity. And without that “eschatological” orientation, we carry on in our blinkered ways, reacting in knee-jerk fashion to our culture, restating the certainties of an irrelevant past. I could go on….

@Andrew Perriman:

“But to be a legitimate sign the community has to live and behave accordingly: as one people, who keep the law written on their hearts…”

This, then, is what you see as the true connection of the eschatological nature of the Bible with morality? In other/my words, rather than turning the Bible into a rule-book, a list of do’s/don’ts, we are signposts, via our behavior, to what’s coming.

Let me ask a probably ignorant question: so is “signpost morality” similar to the New Testament’s discussion of “works” as designating who belongs to what group? (e.g., if I’m circumcised I’m a follower of God.) I’m struggling (I think) to situate morality into a more “proper” place. It’s not the center of the Gospel/sin/salvation, but it still matters.

(I also am struck by your comment about modern Christianity living “without prophetic clarity.” My own (limited) opinion would be that we are so fixated on the morality, we miss what it points to. In an age where everyone has a voice, it can be extremely hard to precisely tune into the prophetic voices among us. Well, maybe this is not so different from the ancient Israelite, faced with many false prophets vs a few cantankerous/backwards-sounding true prophets.)

@Kevin:

Yes, I think you could probably argue that even in the Old Testament the Law is not merely a rule book, it is a code that defines Israel as a certain type of people among the nations—an obedient new creation, on the one hand, a holy and priestly people, on the other. Obviously, the rules need to be obeyed and severe penalties are in place for failure, but there is a symbolic purpose beyond ethical conformity.

My understanding would be that “salvation” in the New Testament consisted in 1) being or becoming—through faith, by the grace of God—part of a reformed people which 2) practiced righteousness 3) for the sake of the “eschatological” purpose of God.

That meant, among other things, identifying with the poor, etc., in Israel, not behaving like the synagogues, not behaving like the Gentiles, and—critically—demonstrating a unity of Jew and Gentile which would prefigure the future rule of Israel’s God over the nations.

So the community of practical “righteousness” only existed because its members believed and trusted in the eschatological narrative about the resurrected Jesus as future judge and ruler both of Israel and the nations. It did not exist because of Law-observance—in fact, the Law and the Prophets now condemned unbelieving and untrusting Law-observant (or non-observant) Israel to destruction.

I agree with your comments about prophecy.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, I’m struggling to frame this. Much of the Evangelical West is obsessed with culture wars such as LGBTQI rights and the transgender issue. Where does the church fit in? A friend says sin is sin and should be called out. Explain please.

@Jason Coates:

I don’t have an easy answer to that question. You could try my book End of Story: Same-Sex Relationships and the Narratives of Evangelical Mission. See if that gets you anywhere.

Otherwise, I would just say that this is one of a number of critical issues that the Western church is having to wrestle with as part of the reconstruction of a workable, forward-looking but not ultimate, “new creation” paradigm or anthropology under secular humanism, or whatever we want to call it.

Inevitably, wrestling with such issues means a furious and unedifying fight between traditionalists and progressivists, but maybe that’s the only way to go.

Thank you, Andrew.

Regarding “It makes no sense, however, to say that he was punished for the sins of the Gentiles”,

Perhaps one could argue that Israel is not alone in responsibility for the looming crisis with Rome. The harshness of Roman overlordship stimulated a harsh response in its Judean subjects.

To the extent that the sins of the Empire contributed to the situation that led to Jesus’ death, perhaps one can affirm that Jesus died for (certain) sins of the Gentiles. But, as with the sins of Israel, these are specific and historical, not universal.

Thank you Andrew.

My question hovers around the sentence:

’Creation is not changed by the fall other than that the man and the woman become subject to death,’

Given that Genesis is an outworking of Israel’s creation myth, presumably the subjection to death of the man and woman is to be understood as metaphor.

@James Mercer:

Doesn’t the expulsion and mortality of Adam and Eve correspond to exile—judgment on Israel, loss of life, expulsion from the land? Isn’t it possible that the authors were projecting back their real experience of death, destruction?

@Andrew Perriman:

Yes, that makes sense.

Recent comments