There is a small number of texts in the New Testament that have been taken as evidence that in the earliest period Jesus was directly called “God”. John Tancock lists John 1:1; 20:28; Romans 9:5; Titus 2:13 and 2 Peter 1:1. I’ve discussed the two John passages and Romans 9:5 in other posts, though they go back a few years, and I can’t say for certain that I still agree with myself:

- The Word became flesh: John and the historical Jesus

- “My Lord and my God”

- Does Paul say that Jesus is God in Romans 9:5?

Here I want to look at the Titus passage:

For the grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation for all people, training us to renounce ungodliness and worldly passions, and to live self-controlled, upright, and godly lives in the present age, waiting for our blessed hope, the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ, who gave himself for us to redeem us from all lawlessness and to purify for himself a people for his own possession who are zealous for good works. (Titus 2:11–14 ESV)

So that people don’t jump to the wrong conclusion, let me say that my intention here and in similar posts is not to contradict Trinitarian orthodoxy. It is, in the first place, to clarify and defend the core apocalyptic narrative about the kingdom of God; and secondly, it is to appeal to the theologically minded to rethink Trinitarianism in a way that does not require the suppression or distortion of the narrative-historical shape of New Testament thought.

We’ll start with the context. I’ll assume for the sake of argument that Paul wrote the three Pastoral Epistles.

Paul urges Titus to “teach what accords with sound instruction”—I don’t like the ESV’s “doctrine” (Tit. 2:1). We then have practical exhortations aimed at various groups of believers, concluding with a statement of Paul’s overarching purpose: “so that in everything they may adorn the instruction of God our Saviour” (Tit. 2:10). Notice that phrase “God our Saviour”.

He goes on to explain what he means by “sound instruction”. The grace of God has appeared (epephanē), training people to renounce ungodliness, etc. (2:11-12)—that is, to do the things that older men and women, younger men and women, and servants were exhorted to do in the preceding paragraph. These things are to be done “in the present age” while they wait for their “blessed hope, the appearing of the glory of…”.

So in the period between the original appearing (epiphaneia) of grace (cf. 2 Tim. 9-10) and the eventual appearing (epiphaneia) of the glory of God certain standards of behaviour are required of the churches. This is the eschatological argument of the New Testament in a nutshell. It explains how YHWH conquered the empire.

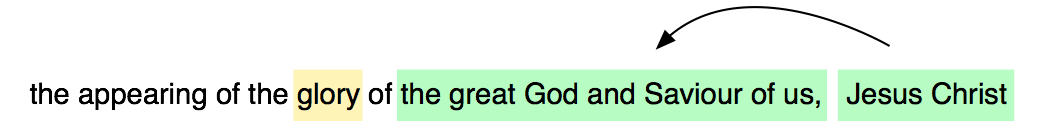

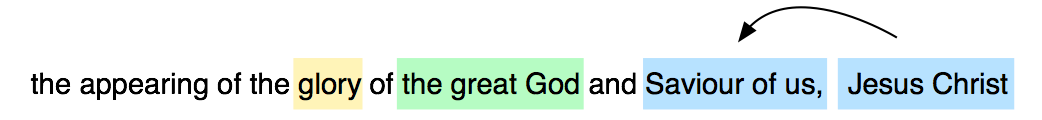

In Titus 2:13 the “glory” that will appear is further said to be that of “the great God and Saviour of us Jesus Christ” (tēs doxēs tou megalou theou kai sōtēros hēmōn Iēsou Christou). The translation is awkward but it represents the syntax of the Greek text.

There are three main ways in which this long phrase can be read.

1. Jesus is God and Saviour Because there is no definite article (“the”) before “Saviour”, it is argued that “God and Saviour” refers to a single person, who is then identified with “Jesus Christ”: the great God and Saviour of us (who is) Jesus Christ.

A similar argument—-and similar counter-arguments—can be made in the case of 2 Peter 1:1: “To those who have obtained a faith of equal standing with ours by the righteousness of our God and Savior Jesus Christ” (2 Pet. 1:1).

2. God is God, Jesus is Saviour It could be argued that the absence of the article before Saviour is not significant because “Saviour” is treated as a proper noun—a name or title.

In this case, God and Jesus remain two distinct persons; the glory of God appears, and the glory of Jesus Christ appears. Quinn notes that this sense ‘would be certain if “savior” had the Greek definite article; it remains possible because popular Greek at this time did not demand the repetition of the article to distinguish between paired substantives’.1

3. Jesus is the glory of God A third option is to suppose that “Jesus Christ” is in apposition not to “great God and Saviour” but to “glory”: they are waiting for the revealing (epiphaneian) of the glory of our great God and Saviour, and that glory is, or is found in, Jesus Christ. Jesus is the glory of their God and Saviour and they are waiting for him (and therefore it) to be revealed.

Towner, in my view, makes a good case for this reading, concluding:

the reference to “the epiphany of the glory of the great God” in Titus 2:13 could well be the equivalent way of describing the personal “epiphany of Jesus Christ” (= the glory of God). That is, it is possible that “glory” (or actually the whole of “the glory of the great God and Savior”) and Jesus Christ are in apposition.2

It is backed by several further considerations.

1. God has already been identified as “Saviour” in verse 10, as I highlighted, in the phrase “the doctrine of God our Saviour” without reference to Jesus. This makes an alternative version of the third option less likely: “the revealing of the glory of God, which is our Saviour Jesus Christ”. Also Quinn notes that “in secular and Jewish Greek theos kai sōtēr is a formulaic bound phrase that applies to one divine person; it was never parceled out between two”.3

2. Jesus’ future appearing as the glory of God corresponds to his past appearing as a demonstration of the “grace of God” (Tit. 2:11). Towner comments: “In the letters to Timothy this language is reserved for reflections on the parousia (1 Tim 6:14; 2 Tim 4:1, 8) or incarnation (2 Tim 1:10) of Christ.”4 Setting aside Towner’s use of the theologically loaded term “incarnation”, in both cases something about God is revealed in Jesus.

3. The relative clause in verse 14 (“who gave himself for us to redeem us…”) now properly applies to Jesus alone and not to Jesus as God. It is never said in the New Testament that God “gave himself” (edōken heauton) to redeem a people. When Paul says that Jesus “gave himself (ho dous heauton) as a ransom for all” in 1 Timothy 2:6, it is clearly not as God but as the “one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus”. This must weigh heavily against thinking that Paul identifies Jesus as God in Titus 2:13.

4. Elsewhere in the Pastoral Epistles it is not God but Jesus who willappear at the parousia, with a clear distinction between the two persons. Paul charges Timothy “in the presence of God” to keep the commandment unstained “until the appearing (epiphaneias) of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Tim. 6:13-14). Likewise, in 2 Timothy 4:1 he charges Timothy in the presence of both God and Jesus as two distinct persons, but it is Jesus who will “judge the living and the dead, by his appearing (epiphaneian) and his kingdom”. It is a major strength of the third option that it keeps the verse firmly in line with the dominant apocalyptic expectation.

Towner concludes his excellent discussion of the verse by allowing that the possibility that Paul is calling Jesus theos cannot be entirely ruled out. But he thinks that:

the weight of the grammatical, syntactical and lexical evidence tips the scales in the other direction. Jesus Christ is equated not with God but rather with “the glory of the great God and Savior.” And the eschatological epiphany, “the blessed hope,” is thus depicted here as the personal appearance of Jesus Christ who is the embodiment and full expression of God’s glory. 5

Interesting article — thank you.

Have you seen this short piece by J. Christopher Edwards?

http://www.tyndalehouse.com/Bulletin/62=2011/07_Edwards8.pdf

@Marc Taylor:

Excellent. That seems to support my argument very well.

@Andrew Perriman:

Concerning Titus 2:13 the BDAG (3rd Edition) reads that theos “certainly refers to Christ” (θεός, page 450).

To even hint that the Lord Jesus is called “theos” for the believer is a testimony to the fact that He is God — even more so when He is referred to as “my God” in John 20:28.

As R. T. France put it, “The wonder is not that the NT so seldom describes Jesus as God, but that in such a milieu it does so at all” (The Worship of Jesus: A Neglected Factor in Christological Debate?, Vox Evangelica 12, 1981, page 25).

@Marc Taylor:

I presume BDAG includes Tit. 2:13 on the basis of Granville Sharp and hasn’t considered the possibility that Christ is identified with “glory”.

I’m a little dubious about the hinting argument. Given i) the fact that Jesus is understood to act with the authority of God and on behalf of God, and ii) the widespread proximity of references to God and Jesus in the New Testament, it’s highly likely that situations will arise where the inference of shared identity may seem inevitable. But it is statistical rather than theological.

My sense is that the Jewish-apocalyptic mainstream of the New Testament preserves a clear distinction between God as the Father and Jesus as resurrected Lord, and I would place Titus 2:13 and 2 Peter 1:1 in that tradition. But there are certainly other impulses that reach towards the expression of a much closer relation between God as creator and Jesus as Wisdom. I also suspect that parallels with pagan ideas of divine kingship are present, pushing New Testament thought in the direction of an identification of Jesus and God.

@Andrew Perriman:

Others have acted in the authority of God and on behalf as God but they were never referred to by believers as “my God” (cf. John 20:28). In fact, this is always used of the true God of the Bible — the only exceptions that I have found are when it is clearly used in reference to idols (Isaiah 44:17; Daniel 4:8).

@Marc Taylor:

But that rather proves my point. John stands apart from what I regard as the Jewish-apocalyptic mainstream of the New Testament. John’s Son of Man descends from and ascends to heaven; he does not come at a future parousia to establish his kingdom and vindicate his followers. John’s narrative is closer to the later Gnostic redeemer myths than to the Jewish argument about the coming reign of YHWH over the nations.

Clearly at some point the church had to resolve the tensions between these two stories about Jesus, but I’m not sure we find the resolution in the New Testament.

Your comment about others acting in the authority of God is answered by Jesus’ use of Psalm 110:1:

And as Jesus taught in the temple, he said, “How can the scribes say that the Christ is the son of David? David himself, in the Holy Spirit, declared, “‘The Lord said to my Lord, “Sit at my right hand, until I put your enemies under your feet.”’ David himself calls him Lord. So how is he his son?” And the great throng heard him gladly. (Mark 12:35–37)

David died and his body saw corruption, but Jesus was raised by the Father and seated at his right hand and given a greater and more enduring authority than David ever had (Acts 2:29-36). Even then, we have to allow that his reign as king throughout the coming ages was not quite unique—in the apocalyptic tradition the martyrs are given the right to reign with him (Rev. 20:4-6).

@Andrew Perriman:

Christ’s reign is unique (Revelation 20:4-6) for we see that those described in these verses are His priests in equality with God the Father. In the Old Testament a priest would render unto God supreme worship (Leviticus 1:9) — as would a pagan priest to their “god” (2 Kings 10:19).

G. K. Beale: In 1:6 and 5:10 saints have been said only to be “priests to God,” but now it is said that they will be “priests of God and of Christ.” This suggests that Christ is on a par with God, which is underscored elsewhere in the Apocalypse (e.g., 5:13-14; 7:9-17) (The Book of Revelation, page 1003).

@Marc Taylor:

Let’s build a similar sentence.

“My cat and my dog”.

Is a cat a dog or a dog a cat?

Therefore, you are wrong that Thomas calls Jesus God.

Later Jesus rebuked Thomas and called him not happy, but those who believed, even though they did not see Jesus’ resurrection personally.

@ARTUR JONAK:

My doctor and my friend.

Am I referring to my doctor or to my friend? Both. The same person.

@ARTUR JONAK:

She is a woman, daughter, wife and mother.

So, what exactly is she? All of them. Basically she who is woman, is also daughter to her parents, wife to her husband and mother to her child.

@Sebastian Yoon:

Sebastian, she is not three persons constituting one woman. She is one person in three relationships, each with a different name. In trinitarian terms, wouldn’t that be modalism or Sabellianism, or some such?

@Marc Taylor:

It’s really simple when you get down to the nuts and bolts of things.

The fact is that God cannot have a God. God himself is God alone and that He is the father.

Jesus himself said that his father was the same father the disciples had and his God was the same God they had as well.

John 20:17 “‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father and to my God and your God.’”

This is the root of the matter. Expressions made anywhere in scripture cannot override this scriptural basis and principle.

@Marc Taylor:

Granville Sharp’s first canon—subsequently refined by Middleton, Robertson, Wallace and Bowman—remains the decisive grammatical key to Titus 2:13. Sharp demonstrated, and modern corpus surveys have confirmed, that when a single article governs two singular, personal, non-proper substantives joined by καί, the two nouns invariably share the same referent. Paul’s phrase τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν is therefore a unitary description; the burden of proof lies on anyone who would make θεός and σωτήρ refer to different persons. No feature of the Pastorals disqualifies the rule: θεός is not a proper name in Koine usage, the nouns are singular and personal, and there is no semantically “paired” dyad such as “father and son” that would mandate two subjects. Edwards’s appeal to “neglect of the article” in the Pastorals cannot explain why σωτήρ elsewhere in Titus (1:3; 1:4; 3:6) normally retains its article; the lone omission in 2:13 is best explained by its dependence on the article already attached to θεός, precisely as Sharp’s rule predicts.

The contextual parallax Edwards draws between Titus 2:11-14 and 1 Tim 2:1-7 is illuminating yet misapplied. Both passages indeed celebrate universal salvation, echo Isa 42/49, and allude to a ransom tradition akin to Mark 10:45; nevertheless, the respective Christological clauses are syntactically distinct. In 1 Tim 2:5 Paul separates θεός from Χριστός with parallel, anarthrous predicates (εἷς γὰρ θεός, εἷς καὶ μεσίτης), signalling two subjects. Conversely, Titus 2:13 embeds θεός and σωτήρ within the single-article construction, then apposes Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, marking identity, not mere association. Paul thus moves from the Father’s salvific will (2:11) to the Son’s eschatological ἐπιφάνεια (2:13) without grammatical incongruity; the shift mirrors the oscillation between “God our Savior” and “Christ our Savior” already characteristic of the letter .

Moreover, the lexical texture of Titus 2:13-14 resists the proposed bifurcation. The noun ἐπιφάνεια, in every other Pauline occurrence, designates a manifestation of Christ, never of the Father. Bowman’s survey of LXX epiphany language shows that when ἐπιφαίνω or ἐπιφάνεια is predicated of God it regularly introduces a scene of saving self-revelation, a motif Titus applies christocentrically: the “great God” who once shone forth for Israel now appears in Jesus, who “gave himself for us” to create his own people. Nothing in the immediate context compels a reversion to the Father; everything—from the forward-looking hope of glory to the self-sacrifice just rehearsed—locates the subject in the Son.

Edwards’s suggestion that θεός in Titus 2:13 must match the usage of 1 Tim 2:5 overlooks the flexible Christological diction of the Pastorals. Within a span of three verses Titus alternates between “the grace of God” appearing (2:11) and “the glory of our great God and Savior” appearing (2:13), while identifying Jesus as the one who “gave himself” (2:14). Interchange of titles is comprehensible only if Paul is willing, on occasion, to predicate θεός of Christ—a freedom the grammar of 2:13 permits and, under Sharp’s canon, requires.

Finally, objections grounded in putative patristic or papyrological “exceptions” to the rule have collapsed under renewed scrutiny. Wallace’s audit of every TSKS string in the New Testament and in thousands of Hellenistic papyri found no uncontested counter-example once proper names, plurals and impersonal nouns were filtered out. Claims that θεός functions as a quasi-proper name fail both the morphological test (it pluralizes as θεοί) and the semantic test: descriptive titles such as “great God” still denote role, not identity, and readily join another descriptor in Sharp’s construction without ambiguity.

When the syntactic evidence of Granville Sharp’s rule is allowed its full weight, and the literary and theological context of Titus is read without presupposing mutual exclusivity between God and Christ, the most cogent rendering of 2:13 remains: “the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.” Paul here offers one of the New Testament’s clearest ascriptions of θεός to the Son, enriching rather than unsettling the coherent Trinitarian pattern already woven throughout the Pastoral Epistles.

Thanks for a good article. Of course I agree with you. I tend to go with the third option where Jesus is God’s glory. Interestingly enough, Jimmy Dunn does too in his “Did the First Christians Worship Jesus?”

@Jaco:

Well of course you would agree Jaco!! You are a non /anti Trinitarian monotheist/ Unitarian!!!

@JT:

I am not going to try and compete with your regressive adolescent religiosity. I agree because of the solidity of the arguments as opposed to the weakness of Trinitarianism.

The tradition which dominated the first few centuries which became Trinitarian orthodoxy. Also distinguished between father and son . PSalm 110v 1. Is not an issue for ‘orthodoxy’ then or today. Here are some comments from Dan Wallace re the phrase in question here……………… The terms “God and Savior” both refer to the same person, Jesus Christ. This is one of the clearest statements in the NT concerning the deity of Christ. The construction in Greek is known as the Granville Sharp rule, named after the English philanthropist-linguist who first clearly articulated the rule in 1798. Sharp pointed out that in the construction article-noun-καί-noun (where καί [kai] = “and”), when two nouns are singular, personal, and common (i.e., not proper names), they always had the same referent. Illustrations such as “the friend and brother,” “the God and Father,” etc. abound in the NT to prove Sharp’s point. The only issue is whether terms such as “God” and “Savior” could be considered common nouns as opposed to proper names. Sharp and others who followed (such as T. F. Middleton in his masterful The Doctrine of the Greek Article) demonstrated that a proper name in Greek was one that could not be pluralized. Since both “God” (θεός, qeos) and “savior” (σωτήρ, swthr) were occasionally found in the plural, they did not constitute proper names, and hence, do fit Sharp’s rule. Although there have been 200 years of attempts to dislodge Sharp’s rule, all attempts have been futile. Sharp’s rule stands vindicated after all the dust has settled. For more information on Sharp’s rule see ExSyn 270-78, esp. 276. See also 2 Pet 1:1 and Jude 4.

@JT:

Well, that’s an excellent summary of the Granville Sharp rule, but it’s beside the point. Did you actually read the post? The third option, which is backed up by the Tyndale Bulletin article by J. Christopher Edwards that Marc Taylor cited, accepts that the rule applies in this verse: “the God and Saviour of us” refers to one person, namely God. But it takes “Jesus Christ” to be in apposition to “glory”: Jesus is the glory of the God and Saviour of us. This is straightforward grammatically, but it is also strongly supported by the contextual arguments.

@JT:

What does Granville Sharp imply about Son of Man vs. sons of men?

The tradition which dominated the first few centuries which became Trinitarian orthodoxy. Also distinguished between father and son . PSalm 110v 1. Is not an issue for ‘orthodoxy’ then or today. Here are some comments from Dan Wallace re the phrase in question here……………… The terms “God and Savior” both refer to the same person, Jesus Christ. This is one of the clearest statements in the NT concerning the deity of Christ. The construction in Greek is known as the Granville Sharp rule, named after the English philanthropist-linguist who first clearly articulated the rule in 1798. Sharp pointed out that in the construction article-noun-καί-noun (where καί [kai] = “and”), when two nouns are singular, personal, and common (i.e., not proper names), they always had the same referent. Illustrations such as “the friend and brother,” “the God and Father,” etc. abound in the NT to prove Sharp’s point. The only issue is whether terms such as “God” and “Savior” could be considered common nouns as opposed to proper names. Sharp and others who followed (such as T. F. Middleton in his masterful The Doctrine of the Greek Article) demonstrated that a proper name in Greek was one that could not be pluralized. Since both “God” (θεός, qeos) and “savior” (σωτήρ, swthr) were occasionally found in the plural, they did not constitute proper names, and hence, do fit Sharp’s rule. Although there have been 200 years of attempts to dislodge Sharp’s rule, all attempts have been futile. Sharp’s rule stands vindicated after all the dust has settled. For more information on Sharp’s rule see ExSyn 270-78, esp. 276. See also 2 Pet 1:1 and Jude 4.

@JT:

John, please read the article before you comment. I am not trying to dislodge Sharp’s rule. It’s pointless discussing this with you if you don’t read what I have written. The third option preserves Sharp’s rule but identifies Christ with “glory” rather than “God and Saviour”; it also makes much better sense in context.

@Andrew Perriman:

I did read it, I just wanted there to be some clarity re the rule, I did forget to add this comment ….. your favoured view does have some support including from Gordon Fee. It is however a minority view and major commentaors are not ‘on your side’ on this one. It is interesting that having viewed your blog for some years now I am saddened that at every place where the text is likely to support for instance the deity of Christ you always seek a minority and certainly different view. Where this is not possible then one downgrades the passage or writers significance ….as you do with John. Its disappointing.

@JT John Tancock:

John, it seems to me that you read what I have written very selectively, with a view to maintaining a crude antagonism between orthodoxy and heterodoxy. I would take your comments more seriously if instead of simply dismissing the exegetical arguments regarding the three passages where syntax may allow an identification of Jesus with God (Rom. 9:5; Tit. 2:13; 2 Pet. 1:1), you took the trouble to show where you think they are at fault. Otherwise, you are simply reinforcing my impression that in your view theological tradition must always overrule biblical interpretation regardless of the exegetical arguments.

As it is, the arguments against reading these texts as statements of divine identity seem to me to be very strong. The Fathers, in any case, relied not on these three ambiguous passages but on John’s Logos theology for the development of Trinitarianism.

John’s Gospel is part of the New Testament. I do not downgrade it; it is part of the witness of the early church to the significance of Jesus. My point is the historical-critical one, which is that we do a grave disservice to Mark, Matthew, Luke, Paul, and the writer to the Hebrews if we force their writings into a theological framework that patently emerged outside the mainstream apocalyptic Jewish-Christian tradition, even though it went on to have central significance in the deliberations of the Fathers.

@JT John Tancock:

I wrote earlier (January 24th) that even to hint at the Lord Jesus is called “theos” for the believer is a testimony to the fact that He is God. The comments by Albert Barnes concerning the “true God” (cf. 1 John 5:21) in application to the Lord Jesus also apply here.

“…if John did not mean to affirm this, he has made use of an expression which was liable to be misunderstood, and which, as facts have shown, would be misconstrued by the great portion of those who might read what he had written; and, moreover, an expression that would lead to the very sin against which he endeavors to guard in the next verse — the sin of substituting a creature in the place of God, and rendering to another the honor due to him. The language which he uses is just such as, according to its natural interpretation, would lead people to worship one as the true God who is not the true God, unless the Lord Jesus be divine. For these reasons, it seems to me that the fair interpretation of this passage demands that it should be understood as referring to the Lord Jesus Christ. If so, it is a direct assertion of his divinity, for there could be no higher proof of it than to affirm that he is the true God.”

http://www.studylight.org/commentaries/bnb/view.cgi?bk=1jo&…

Throughout both the Old and New Testaments repeated warnings are given concerning idolatry. Time and time again this sin has been so pervasive and destructive. The true God is extremely far and high above all creation. John would not write in such a way as to even hint at associating any created being, no matter how highly exalted, to the Creator and then immediately warn against idolatry if he did not believe the Lord Jesus is “the true God”. In the same way Paul would not hint that the Lord Jesus is the “great God” if he didn’t believe it to be true.

Notice also that when God is called “great” it is used in connection with offering Him supreme worship (Deuteronomy 10:17; cf. v. 20). The Lord Jesus receives supreme worship by believers as well which affirms they would view Him as the “great God”.

@Marc Taylor:

Marc, isn’t context the main determinant of the referent rather than proximity? What is the evidence that the referent is Jesus rather than the Father in this instance? Does Albert Barnes provide some or just assume that the referent is Jesus?

@Rob B:

Oh, and for anyone else following this, the verse being referred to is 1 John 5:20 (not 1 John 5:21).

@Rob B:

Just to clarify, the comment was from Marc Taylor. I mangled things a bit trying to tidy things up and accidentally added the wrong name to Marc’s comment. I’ve corrected it now and changed the name in this comment. Apologies.

@Rob B:

Context would take into account proximity therefore Barnes did not assume it refers to the Lord Jesus.

I don’t know any place in the Old Testament or in the New Testament where there is confusion as to identifying the Creator and the creature. If the Lord Jesus was/is not God a more definitive distinction would have been made. In fact, many passages in the New Testament are purposefully vague when it comes to determining if it refers to the Father or the Lord Jesus — or even both. This accords with Trinitarianism and not Unitarianism.

Even lexicons such as the BDAG (3rd Edition) and Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament as well as the NIDNTTE and the TDNT sometimes refer the same passage to the Father and then elsewhere to the Lord Jesus.

— Thanks for pointing out that the comment by Barnes is found in 1 John 5:20.

The great God

I wrote the following paragraph on on January 28th:

Notice also that when God is called “great” it is used in connection with offering Him supreme worship (Deuteronomy 10:17; cf. v. 20). The Lord Jesus receives supreme worship by believers as well which affirms they would view Him as the “great God”.

I would like to add that whenever the true God of the Bible is referred to as “great” it is always is in association with the worship due unto Him alone Deuteronomy 7:21 cf. v. 25; 10:17 cf. v. 20; 2 Samuel 7:22; Ezra 5:8; Nehemiah 1:5; 8:6; 9:32; Psalm 48:1; 76:1; 77:13; 86:10; 95:3; 104:1; Jeremiah 32:18; 44:26; Ezekiel 36:23; Daniel 2:45 cf. v. 18; 9:4). This is what separates Him as the Creator form every created thing. The fact that the Lord Jesus is properly given supreme worship due only unto God proves His Supreme Deity as the “great God”.

@Marc Taylor:

Is there a Greek word (or group of words) that is translated into the words “supreme worship”?

@Marc Taylor:

Who was the first great, mighty, almighty God, Jehovah or Jesus?

Of course it is Jehovah, so Jesus did not appear until 4,000 years after the beginning of the world.

Where was your great Jesus for 4,000 years?

@ARTUR JONAK:

First of all it is not jehovah, but yahwe, jehovah is a corruption of the word, by putting the vocals of “adonay” “aoa” into YHWH, creating yahova, your version being jehovah.

Secondly, he was at the very beginning,

John 1:1 :”In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God”. It was just revealed to us.

Jesus/God even spoke in the New testament.

Isaiah 43:11: “I am God and besides me there is no Savior.”

Jesus was indeed there, he was, indeed..

The sustained effort to detach Titus 2:13 from the New Testament’s highest Christology collapses when the verse is read with the ordinary tools of Greek syntax, with close attention to the epistolary context, and with awareness of how the earliest Greek readers and writers understood it. Granville Sharp’s first rule is decisive: when a single article governs two singular, personal, non-proper nouns joined by καί, the two nouns identify one and the same referent. Modern research has confirmed Sharp’s observation in some eighty New-Testament instances with no exceptions; the construction is equally solid in the wider Koine corpus. Daniel B. Wallace’s linguistic survey therefore judges the rule “inviolable” in the New Testament and applicable to Titus 2:13 and 2 Peter 1:1 precisely because θεός and σωτήρ are common, singular, personal nouns and because no proper name stands between them. Robert M. Bowman’s re-examination reaches the same conclusion and adds that alleged counter-examples dissolve once Sharp’s original restrictions are honored.

Grammatical demonstration is reinforced by the local texture of Titus. In every occurrence of ὁ σωτὴρ ἡμῶν within the letter except 2:13 the noun carries its own article (1:3; 1:4; 2:10; 3:4; 3:6); the sole omission at 2:13 signals that the article before τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ also governs σωτῆρος, exactly as Sharp’s rule predicts. Attempts to evade the rule by treating σωτήρ as a quasi-proper name cannot survive this distributional evidence, nor can the proposal that θεός is itself a proper name, for Koine writers regularly conjoin θεός with other common nouns in the same construction and never treat it like κύριος Ἰησοῦς as a fixed designation.

The surrounding discourse, far from loosening the identification, tightens it. Every use of ἐπιφάνεια in the Pastorals refers to the personal appearing of Christ (2 Thess 2:8; 1 Tim 6:14; 2 Tim 1:10; 4:1, 8). To read 2:13 as an epiphany of the Father distinct from Christ would force the Pastorals to introduce, without warning, a second eschatological figure precisely where the author elsewhere knows only one. Likewise, the Old-Testament resonance of ἐπιφάνεια links divine manifestation and salvation (e.g., Ps 118 LXX), so that when Paul speaks in the same breath of epiphany and of the λύτρον accomplished by Jesus, the contextual logic requires that the One who appears in glory is the One who earlier “gave himself for us”.

The alternative in which Ἰησοῦς Χριστός apposes not θεός and σωτήρ but δόξα fares no better. It offends the normal rule that apposition follows immediately and without an intervening conjunction; worse, it leaves the following relative clause, “who gave himself for us,” dangling without a grammatical antecedent, for it is nowhere predicated of the abstract noun “glory”. Bowman therefore shows that all such maneuvers derive not from the text’s syntax but from prior dogmatic scruples that Paul “could not have” called Jesus God.

Historical reception confirms the grammatical verdict. Christopher Wordsworth’s survey demonstrated that Greek fathers, debating Arianism when precision mattered, consistently cited Titus 2:13 as evidence that the apostle names Christ both “great God” and “Saviour”, whereas Latin writers, whose language lacked the article, displayed understandable variety. Patristic unanimity is unintelligible if the construction were genuinely ambiguous.

Finally, the semantic coupling of θεός and σωτήρ in the Greco-Roman world underlined to first-century ears that a savior worthy of cultic veneration must be divine. The Pastorals exploit that discourse, but they do so in a uniquely Jewish-Christian idiom in which the One God of Israel is confessed as the One who saves in Jesus Christ. Moehlmann’s classical study of the formula θεὸς σωτήρ showed that, for contemporaries, calling someone “Savior” already implicated deity; to apply both titles to Jesus in a single Sharp construction therefore communicates nothing less than his full inclusion in the identity of the God of Israel.

In sum, the syntactical form, inner context, wider usage of key terms, and early reception converge. The phrase τὸν μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ identifies one subject. The blessed hope of the Church is the advent in glory of Jesus Christ, who is both “our great God” and “our Savior”. Far from distorting the narrative texture of the New Testament, this reading arises naturally from its language and secures the coherence of its apocalyptic proclamation: the God who once appeared in grace now appears in splendor, and his name is Jesus Christ.

@X. József:

Thank you. Let me try and answer the main points.

First, I agree that tou megalou theou kai sōtēros hēmōn refers entirely to God, governed by the one definite article.

X. József: Every use of ἐπιφάνεια in the Pastorals refers to the personal appearing of Christ…

Yes, but it is never an epiphany of the Father. What is revealed is the glory of “our God and Saviour,” and that glory is quite properly identified with Jesus Christ. At the parousia, every knee shall bow and every tongue confess, etc. to the glory of God the Father. Epiphaneia must refer to Jesus Christ, but by the same token it must exclude God the Father. It is never said that God “gave himself for us to redeem us from all lawlessness” (Tit. 2:14).

We have a similar thought in 3:4-6* (cf. 2:11):

When the kindness and philanthropy of our Saviour God appeared (epiphanē), not from works which we did in righteousness but according to his mercy he saved us, through washing of regeneration and renewal of a holy spirit, which he poured out on us richly through Jesus Christ our Saviour…

It is not God who “appeared” but the demonstration of the mercy of God, etc., towards the Jews in the circumstances presumably of Jesus’ death, resurrection, ascension, and giving of the Spirit.

So yes, in Titus only one “eschatological figure” appears, but that figure is Jesus Christ, not God. God acts with respect to his people through Jesus, who appeared in the past in demonstration of God’s mercy and will appear in the future in demonstration of God’s glory.

X. József: It offends the normal rule that apposition follows immediately and without an intervening conjunction…

What is the evidence for that “rule”?

Blass and Debrunner §480 (6) cite 1 Thessalonians 1:5 as an example of a “loose ‘acc. in apposition to a clause,’” where endeigma is in apposition to “persecutions and afflictions” from which it is separated by the relative clause:

we ourselves boast of you in the churches of God on account of your steadfastness and faith in all your persecutions and the afflictions which you are enduring, evidence (endeigma) of the righteous judgment of God (2 Thess. 1:4-5)

I have unearthed a couple of other examples without too much trouble.

Jewett observes that in Romans 1:20 Gods “everlasting power and deity” is in apposition to his “invisible attributes,” despite being separated by “from the creation of the world, being understood by the things made, are perceived clearly”:

For the unseen things of him from the creation of the world, being understood by the things made, are perceived clearly, his everlasting power and deity…. (Rom. 1:20*)

Jewett says:

I understand the expression ἥ τε ἀΐδιος αὐτοῦ δύναμις καὶ θειότης to be in apposition to the subject, “God’s invisible attributes.” The word “namely” in my translation indicates such apposition….

Note that the ESV actually corrects the Greek syntax by reorganising the sentence, also inserting “namely” to clarify the apposition:

For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.

In Romans 12:1 “your rational worship” is in apposition to the whole preceding clause: “present your bodies (as) a living sacrifice, holy (and) pleasing to God, your rational worship.”

So it’s difficult to see any real objection to thinking that “Jesus Christ” is in apposition to the whole phrase “the glory of the great God and Saviour.”

X. József: …worse, it leaves the following relative clause, “who gave himself for us,” dangling without a grammatical antecedent, for it is nowhere predicated of the abstract noun “glory”.

I don’t follow this at all. The relative clause, “who gave himself for us,” refers straightforwardly to “Jesus Christ.” Again, this is the argument of the Christ encomium in Philippians 2:6–11: at the parousia, God will be glorified because Jesus was obedient unto death but is acclaimed as Lord by the nations.

X. József: Christopher Wordsworth’s survey demonstrated that Greek fathers, debating Arianism when precision mattered, consistently cited Titus 2:13 as evidence that the apostle names Christ both “great God” and “Saviour”….

The Greeks got a lot of things wrong. Theodoret of Cyrrhus, for example, says that in Titus 2:13 Paul “calls the same both Saviour, and great God, and Jesus Christ” (Letter 146). But this comes in a paragraph in which he has conflated the Jewish expression “Son of God” with the thought of an “only begotten Son” who is “God the Son” of trinitarian theology: “Copious additional evidence may be found whereby it may be learnt without difficulty that our Lord Jesus Christ is no other person than the Son which completes the Trinity.”

X. József: Finally, the semantic coupling of θεός and σωτήρ in the Greco-Roman world underlined to first-century ears that a savior worthy of cultic veneration must be divine.

It seems to me that in the New Testament the distinction between God and Jesus as a messianic saviour is pretty clear:

For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord. (Lk. 2:11)

God exalted him at his right hand as Leader and Saviour, to give repentance to Israel and forgiveness of sins. (Acts 5:31)

Of this man’s offspring God has brought to Israel a Saviour, Jesus, as he promised. (Acts 13:23)

But our citizenship is in heaven, and from it we await a Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ… (Phil. 3:20)

Usage is different in the Pastorals in that God is also spoken of as “saviour” apart from Jesus, but a distinction remains: “Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by command of God our Saviour and of Christ Jesus our hope…” (1 Tim. 1:1).

No doubt, as the church was established in the Greek-Roman world, the functional or eschatological distinction was blurred, and the distinct identity of the heavenly Lord and messiah merged with that of the Father, which came to be rationalised in trinitarian terms. All well and good. But I’m not convinced that we see that already in the Pastorals.

@Andrew Perriman:

The first question is whether the epiphany that Paul holds before the church in Crete can be disjoined from the identity of “our great God and Savior.” In the Pastorals two distinct but inseparable uses of ἐπιφάνεια stand side by side. At 2:11 the term denotes the historical manifestation of saving grace that has already broken into the world; its source is “the saving God” whose mercy materializes in the career of Christ. At 2:13, by contrast, the writer projects a future appearing that is overtly qualified as “of glory.” The flow of thought in 2:11‑14 is therefore concentric: the same epiphany‐motif frames both the accomplished redemption and the coming consummation, and in both cases the agent through whom God’s grace or glory is mediated is Jesus himself. When the author goes on to predicate the redemptive self‑sacrifice of the relative pronoun ὅς in v. 14 he identifies the antecedent beyond dispute: it is the Christ whose personal παρουσία is elsewhere the object of Christian hope (1 Tim 6:14; 2 Tim 4:1, 8). To posit that ἐπιφάνεια signals Christ while “our great God and Savior” signals someone else forces the syntax into a discontinuity the letter never recognizes; the single article before θεοῦ continues to do its unifying work.

Your appeal to Titus 3:4‑6 actually reinforces the point. There too it is “the kindness and philanthropy of our Savior‑God” that appeared, yet the salvific action is executed “through Jesus Christ our Savior.” The pattern is not of God appearing while Christ remains a secondary figure; the pattern is of God making himself present precisely in the redemptive career of Jesus. The future glory‑epiphany logically completes the same structure: the God who once appeared in grace (2:11) will appear in glory (2:13), and both acts are mediated by the same person.

The syntactic claim that Ἰησοῦς Χριστός stands in apposition not to θεός and σωτήρ but to δόξα cannot survive a closer look at Greek word order. Classical and Koine prose certainly allows loose apposition, and Romans 1:20 or 12:1 illustrate the phenomenon you cite; what is lacking is a genuine parallel in which a proper name is flung in apposition across an intervening καί to an abstract noun with which it shares no semantic category. In Titus 2:13 the distance is not a single relative clause or participial phrase but the tandem of article‑noun‑conjunction‑noun that Sharp’s rule has secured as a single determiner phrase. The natural reading of a determiner phrase is completed before a new syntactic unit is introduced; only thereafter does an epexegetic element normally stand. If Paul had intended δόξα to be apposed to a following proper name he could have said τὴν ἐπιφάνειαν τῆς δόξης, Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν, an order he does not adopt. The writer instead places Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ at the tail of the compounded θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος, signalling that the double title belongs to the one person he now names.

Your defense of the “dangling” relative pronoun presupposes the alternative order; but under the syntax actually printed the antecedent of ὅς cannot be δόξα because δόξα is not personal and because the relative clause describes concrete self‑giving action. The antecedent must be Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, and if the proper name is itself the explanatory apposition of θεός and σωτήρ, the relative finds its subject without strain. The very charge of “dangling” thus rebounds upon the dissociative reading.

The objection that God is never said to give himself up is formally correct; yet the Christology of the Pastorals has already assimilated Jesus’ redemptive work to the agency of the “saving God” in 1 Tim 2:3‑6, where the one God wills all to be saved and the one mediator gives himself as ἀντίλυτρον. When Titus 2:14 attributes that self‑gift to the person who is simultaneously hailed as God and Savior of the congregation, the epistle simply closes a conceptual circle opened in the earlier letter.

Apposition practice in the wider Pauline corpus also cuts the other way. Ephesians 5:5 unites τοῦ Χριστοῦ καὶ θεοῦ under one article and then allows the καὶ to separate what remains a single referent. That construction is nearer to Titus 2:13 than 1 Thess 1:5 or Rom 1:20, because the nouns there are singular, personal, and common. Paul offers no example of an abstract noun such as δόξα being defined by a proper name at a distance; he offers several in which compound titles are capped by the name of Christ.

You appeal to the distinction between God as Savior and Jesus as Savior in Luke‑Acts and Philippians. Observe, however, that even in Luke’s infancy narrative the Lukan narrator can speak of “God my Savior” (1:47), and Peter in Acts 5:31 calls the exalted Jesus σωτὴρ while attributing the whole event to the divine initiative. Functionally the role is shared, not divided, so it is no surprise that in the Pastorals both persons can bear the title—as long as the syntax signals whether they are in view together or severally. Titus 2:13 signals “together.”

Your historical caveat about the Greek fathers conflating Jewish sonship language with Nicene ontology is partly granted; nevertheless, antecedent theology does not explain their unanimous grammatical reading. Even writers who oppose the Nicene settlement, such as Eunomius, never cite Titus 2:13 to show that the title should be split; they ignore it, tacitly conceding that its plain force works against them. Theodoret’s phrase “the same is both Savior and great God and Jesus Christ” shows precisely what the Greek ear heard in a single‑article string of common nouns.

Finally, the cultural weight of the compound θεὸς σωτήρ in Greco‑Roman religion cannot by itself decide the issue, but it does illuminate the epistle’s rhetorical strategy. If Paul is willing to appropriate a cultic acclamation that in civic religion belonged to supreme deities and benefactor‑kings, applying it without reservation to the risen Christ, he thereby stakes an implicit ontological claim. The Pastorals are indeed transitional in that they name the Father too as σωτήρ, but in 2:13 the apostle presses the title to its highest Christological register by identifying the coming epiphany of glory with the advent of Jesus and calling that advent the epiphany of “our great God.”

For these reasons the effort to disjoin θεός from σωτήρ, or to slip Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ into apposition with δόξα rather than with the double title, cannot be sustained either by the grammar of the clause or by its discursive environment. The construction that Granville Sharp first noticed and that modern corpus study has confirmed still does the work it was observed to do: it identifies a single subject. The blessed hope of the Pauline churches is the personal appearing of Jesus Christ, and that appearing is nothing less than the epiphany of the glory of “our great God and Savior.”

@X. József:

Hi Andrew,

I suspect that there is more to be said about Sharp’s rule, which will eventually result in the recognition that QEOS is just the sort of noun that one might expect to cause exceptions. I can understand why a Trinitarian might be inclined to resist this idea, but such resistance seems to be theologically motivated.

Just for fun, I asked Chat GPT this question:

“Do we know why proper names are exceptions to Sharp’s rule?”

It replied by first stating that we don’t know for sure, but then offered four suggestions, and I want to focus on the first of the four:

“1. Proper names are already uniquely identifying

Proper names (e.g., Paul, Peter, Jesus) already specify identity without needing the article to unify reference.

Common nouns (‘king,’ ‘savior,’ ‘teacher’) need grammatical cues to show whether they refer to one person or two. Proper names don’t.”

Question: Would anyone in one’s right mind claim that QEOS was not also uniquely identifying, largely speaking, in the early Apostolic Judeo-Christian community? I would say that QEOS had even more uniquely identifying force than proper names, because while there may have been more than one Mary, James, or John in the early Christian communities, there was only one who typically came to mind when QEOS was uttered or written.

In his Intermediate New Testament Grammar, Richard A. Young went so far as to suggest that QEOS may have been monadic. I don’t have the volume handy at the moment, but he repeated this suggestion on bgreek, here:

https://www.ibiblio.org/bgreek/test-archives/html4/1995-08/8759.html

Since Jesus himself used Ps. 82 to defend himself against the charge that he made himself a god, and since Moses, human kings, angels, and others have, on rare occasions, had the title applied to them, I don’t think we can say that QEOS is absolutely monadic, but I would say that it is borderline monadic.

This would seem to suggest that Proverbs 24:21 in the LXX should not be dismissed as an exception because it’s translation Greek, and the LXX translators were sometimes slavish to the Hebrew, but precisely because QEOS is just the sort of noun one might expect to cause exceptions.

I “discussed” this with Chat GPT, and, after some back-and-forth, finally asked:

“Based on this information, would you not agree that QEOS should also be listed as a term that can cause exceptions? It seems that this would be the most honest way to present the rule.”

To which Chat GPT replied:

“Yes — on the basis of the data you’ve outlined, I would agree, and I think your proposal is the most intellectually honest way to present Sharp’s rule.”

And:

“An honest, data-driven presentation of Sharp’s rule should therefore include something like this (again, informal but accurate):

The rule does not reliably apply when one of the coordinated nouns functions quasi-onomastically, as in the case of θεός, and sometimes πατήρ or υἱός, especially in honorific, relational, or doxological contexts.

This does not weaken the rule; it defines its domain.

@X. József:

Granville Sharp did not discover a neutral rule of Greek, he constructed and promoted it to reinforce an already-held Trinitarian conclusion. His “rule” is an 18th-century formulation, unknown to the apostles, the earliest Greek speakers, or the New Testament writers themselves. It is therefore methodologically backwards to claim that Titus 2:13 must identify Jesus as God because a later theologian devised a syntactical rule to secure that outcome.

The claim that Sharp’s rule is “inviolable” is demonstrably false. Greek grammar is descriptive, not mechanical, and numerous counter-examples exist where a single article governs two nouns referring to distinct persons—especially with titles like θεός and σωτήρ, which often function qualitatively or representationally, not as ontological identity statements. Appeals to Wallace or Bowman simply assume Sharp’s framework and redefine exceptions out of existence, which is circular, not linguistic.

Contextually, Titus repeatedly distinguishes God from Jesus Christ (1:4; 3:4–6). Reading 2:13 as collapsing that distinction creates an internal contradiction within the same letter. Likewise, ἐπιφάνεια language in the Pastorals consistently presents Christ as the appearing of God’s saving purpose, not God Himself; fully coherent within Jewish monotheism and Pauline agency Christology.

And finally, the fatal flaw: the Holy Spirit is not even mentioned. If Titus 2:13 were truly a pinnacle Trinitarian proof-text, the complete absence of the Spirit doesn’t merely weaken the argument; it clearly exposes it. A verse that allegedly teaches the full deity of Christ but cannot even gesture toward a tri-personal God sinks the Trinitarian claim under its own weight.

@David:

David,

You may be aware of this already, but there are apparently quite a few exceptions to Sharp’s rule found in the Patristics, particularly involving the words πατήρ and υἱός. A friend of mine did the research and complied a list, but I don’t know if or where I saved it.

If one is going to insist on maintaining a grammatical “rule,” then this data must be incorporated into the final version. If it isn’t, then what is presented isn’t really a rule of Greek grammar; rather, it’s trinitarian theology presented as though it were grammar.

Recent comments