At the Communitas conference, conversations focused on human sexuality and a “quiet revival” among young people. Lamorna Ash’s Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever chronicles her journey through diverse Christian traditions, seeking a faith less dogmatic and more inclusive, especially toward LGBTQ+ people. She critiques shallow biblical interpretation and urges historical reading. The author frames church history as four eras, with the current transitional age shifting from Christendom to a priestly, marginalised role. This demands grappling with new understandings of humanity and sexuality. Ash’s takeaway: genuine love crosses faith boundaries when we take others’ lives as seriously as our own.

At the Communitas staff conference in Malaga last week, there was a lot of discussion around two related topics: human sexuality and the surprising interest shown by young people in Christianity in the last few years, which sometimes goes under the label “quiet revival.”

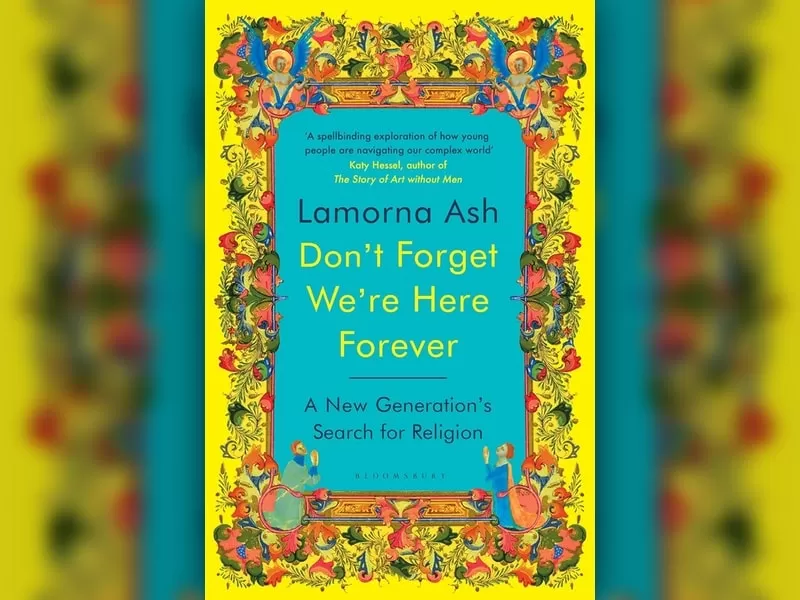

On the flight back, I started reading Lamorna Ash’s book Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion. It’s really an account of her own personal search for a plausible and sustainable form of Christianity, but we learn a lot along the way about what other young people are thinking. It’s a good, honest, serious, stimulating book, and Ash has become something of a minor celebrity, it seems, in the Christian podcast world. Look her up.

This is not much of a review of the book, but I will use it as a starting point for some cautious reflections on how the forward-looking church might proceed. What are the implications for our understanding of the Bible? How do we position ourselves in a changing world? I’ve been reading the Kindle edition so I won’t include page numbers.

The journey

Ash starts by attending the Christianity Explored course at All Souls Langham Place in London, and is a little scathing about how Rico Tice would “swagger and quip his way through the week’s theme.” At the same time, she has begun to date women, so the spiritual journey gets off to a rather bumpy start. “In this version of Christianity, the first I had been offered, it felt like there was harm stitched into the other side of its welcome.”

She then attends a mass baptism at an “Evangelical Alliance church,” and rebels against “the predictive, seductive mode of testimony…, which seemed to turn lives into commodities, ‘before and after’ advertisements for Christianity.”

Throughout the book, her commentary on the diverse forms of Christianity that she encounters is astute.

She is more sympathetic towards the youthful enthusiasm of the YWAM community in Harpenden, who “lived as if the time of Acts had never ended.” But she is still troubled by the “flexible ontologies” (Luhrmann) by which the failures of faith are accommodated, by the diluted colonialism of their missionary work, and by what she presumably perceived as an undercurrent of sexual repression.

From there she goes in search of a version of Christianity that is less demanding, less intolerant, less dogmatic, less incompatible with the chaotic circle of friends with whom she gets drunk, dances at “grotty house parties,” and explores her sexuality. In the end, she seems most at home amongst Quakers in Muswell Hill, in the gay-affirming One Church in Brighton, and in what sounds like a rather dilapidated Anglican church in north London.

The diverse menagerie of fellow pilgrims she meets and interviews along the way are mostly of a similar mind. A few are moving in a more traditional or conservative direction, but she is clearly attracted towards individuals and communities on the “progressive” side of the deep fracture that separates the two major tectonic plates of the modern church. Are more migrating to the right than to the left? That’s not clear. Are more young men migrating to the right, more young women to the left?

Ash quotes an Orthodox priest with a pervasive online presence, Father Spyridon Bailey: “It is [a] worldwide pattern, many young men are seeking Orthodoxy. Secular materialism has shown itself to be incapable of answering our deepest needs.” She is disappointed that Father Spyridon, like Rico Tice, puts all the emphasis on the individual to the neglect of the relational and social dimensions of, for example, “misogyny and rape culture.”

It seems likely that towards either extreme—the orthodox and the progressive—the search will slide into disordered and damaging patterns of “religious” ideology and practice.

The Bible

At risk of sounding patronising, I will say that she does quite a good job of telling parts of the biblical story along the way.

I liked how she changed her mind about the Babel story. Her first thought is that a small-minded god hates the idea of humanity getting to heaven unaided. Then, with the help of Bruegel, she comes to understand that Babel is “also the symbol for man’s desperate, self-destructive need to reach greater and greater heights.” It presages the tech billionaires and the devastating consequences of technological progress. Yes, it can be made to do that, I think.

But I would fault her therapeutic retelling of Mark’s Gospel as an account of how Christ “altered the ordinary lives of those inhabiting the Levant region… in the first century CE.”

She finds in the voice crying in the wilderness (Mk. 1:2-3) echoes of the opening of Genesis rather than of Isaiah 40. This is the voice of the God who cried, “Let there be light.”

The people of Judea suffered acute physical and mental health problems, their “little faith was beset on all sides by worldly temptations,” so they came to be baptised in the “cathartic waters” of the Jordon.

This sounds suspiciously like a Gen Z narrative projected on to the political-religious crisis faced by first century Judaism.

When Jesus is baptised, the light enters the world for a second time. His encounter with God was “so overwhelming a dose of acid that he had to walk out alone into the silence of the desert.” As Ash understands it, this is “the opening scene of a brand-new religion.”

That’s an unhelpful way of putting it. As long as we are committed to the whole of scripture, we cannot speak of what emerges as a “brand-new religion.” That is wrong in so many ways.

Sometimes, however, she is spot on. Someone tells her that God has given him a new heart, quoting Ezekiel. She notes the exilic context of the original statement and comments:

So often when I discovered the origin of a biblical quotation used by someone I interviewed, the context which emerged like a sea around its islanded sentiment rendered it unworkable for the circumstance in which it had been offered.

Exactly! Now go back and read Isaiah 40:1-11.

An opportunity to be taken

It’s probably too much to hope for, but if a younger generation is reading the Bible for the first time, with fresh eyes, free from the distorting effects of our blinkered theologies, we have an opportunity at least to ground such reflection in a historical reading of the text—before it gets recycled to furnish form and language for our own experiences.

The Bible Society’s Quiet Revival report says that young Christians in England and Wales “have less confidence in the Bible” than older generations and are more troubled by what they find in it. That’s at least a sign that they are reading honestly. They are not subconsciously filtering out content which does not conform to their moral and theological presuppositions.

But to see this as an “opportunity to tap into and learn from their energy and enthusiasm while enabling them to go deeper into Scripture” is self-serving—an encouragement to assimilate minds into old biases, to funnel new wine into old wineskins, we might say. Going “deeper into Scripture” is a tired evangelical trope.

The reverse should happen. The older church should seize the opportunity to abandon the heavily signposted, straight, narrow pathways of its traditions and venture into the disorienting forest of biblical history.

The only Jesus who can “save” us—whatever we mean by salvation—is the Jesus of history, not the Jesus of the moral imagination or of the pietistic imagination.

But history doesn’t stop—didn’t stop on the day of Pentecost. We are on a moving conveyor. Even if we all stand still, we will be carried forward into a different future. So we need to keep telling the story.

A divine comedy in four parts (so far)

A good literary analogy would be a tetralogy of related plays or other works, each with its own self-contained narrative logic, its beginning and end. I have previously suggested the Shakespearean trilogy (i.e. Henry VI), in contrast to N. T. Wright’s restrictive five act play hermeneutic. But I think that we are already seeing the emergence of a fourth significant era in the saga of the people of God.1

Part One covers the biblical story about God’s people and the land and the clash with ancient empire: from the building of the city of Babel to the destruction of Babylon the great. This views the New Testament as the fulfilment of an expectation that surfaces in the exilic period—that the pagan nations which have dominated Israel’s world for so long will abandon their idols and, one way or another, serve the one God who made the heavens and the earth (cf. Is. 45:20-46:2; Phil. 2:9-11).

Part Two tells the story of the rise and expansion of European Christendom. This long period was the concrete historical fulfilment of the expectation that arose in part one—the Bible’s happy-ever-after.

We are now well into Part Three, perhaps nearing its end, which is the story of modernity and its devastating and demoralising impact on the church. It should probably be seen as transitional.

Part Four will cover the consolidation of a reconstituted humanity, a new, increasingly globalised anthropology, subject to very different internal rules and definitions, in an uneasy, destabilising relationship with its technology, as it suffers what are likely to be the severe birth pains of the Anthropocene.

If we are in a transitional age, however, we may expect the church to be stretched along the time-line, stuck in the past, pulled into the future. It would be easy to characterise this as a straightforward conflict between conservative and orthodox Christianity and progressive Christianity, but I think the direction of travel may cut obliquely across this line—perhaps even at right angles to it. At least, I think that there is more than one way to be progressive and more than one way to be orthodox.

From civilisation to priesthood

So there are two important lines to be drawn, to be expounded: the story-line running through scripture and history to the present and on into the future; and the line that we are crossing between Christianity as civilisation and the church as priestly community, which defines the experience at the narrative heart of Part Three of our tetralogy.

The New Testament envisages a monotheistic, Christ-honouring civilisation in place of the pagan, Greek-Roman oikoumenē, which would become the Christian West. It does not envisage a redeemed humanity, so when Christendom grows old and dies, we revert to the priestly paradigm. I suggest that the church in the West is in the process of working out in thought and practice what that means.

The church is no longer at home in its world. As Israel was among the nations, it has become again a marginalised, contrary, uninvited presence, mediating between an evolving humanity and the living God who made the heavens and the earth.

The church is no longer a vestige of a Christian civilisation; it is a prophetic priesthood and must engage with the future.

So perhaps people like Lamorna Ash may help us to understand better what sort of thing the church needs to be in this transitional moment. It is becoming easier to imagine a properly post-Christian world, a world to come, but it is a world underpinned by some very different assumptions about what it means to be human.

So if the church is to move forward into a priestly function, it has to come to terms, in the first place, with the divergence between two quite differently constructed notions of human sexuality.

That should be seen as a structural challenge.

There are church buildings which provide a sacred space and a physical connection with the past, with the Christendom era. Ash wonders why so many of her friends, at times of inner turmoil or crisis, have ended up in church, “engaged in something that approximated prayer.” The reason is that “there are no other public spaces which fulfil this requirement, acting as portals to direct you to places outside of your ordinary modes of thought.”

Buildings are safe spaces, communities less so.

There are churches which are determined to embody not historical continuity, even if they gather in an old building, but doctrinal or experiential normativity. These are the more conservative evangelical, charismatic, and Pentecostal churches. They are the product of the third play in the tetralogy—the reaction against the depredations of modernity. They must be taken seriously because they have preserved through troubled times both a stubborn loyalty to scripture and the experience of the Spirit of the living God; and arguably they are flourishing, at least in relative terms, for just that reason.

But these churches seem ill-positioned to meet with the LGBTQ+ people who are perhaps currently the most visible index of what humanity is slowly becoming.

They have their openly inclusive counterparts, such as One Church in Brighton, and there are, of course, many mainline churches which provide a refuge for LGBTQ+ people.

But we are left with the problem of what we do with the rift, and I suppose what I am wondering is whether communities and missions and perhaps even individuals that understand and embody a priestly vocation that is oriented towards the future have a particular contribution to make here.

I’ll leave it there for now and will finish with an optimistic and quietly subversive quote from the book that needs to be heard by people on both sides and lived out by gifted communities somewhere in the middle:

You can love people from across the borders of your faith. All it requires is that you to take their life as seriously as you take your own. In such cases, to all intents and purposes, the borders come down anyway.

- 1

In fact, the three Henry VI plays with Richard III are regarded as a second tetralogy by scholars after the first tetralogy of Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 and 2, and Henry V.

Recent comments