The text critiques the church’s fixation on “mission,” arguing that biblically mission is a reactive response to crisis, while priestly action is the church’s normal vocation. A narrative-historical missiology is proposed, framed by synchronic (present context) and diachronic (history) axes. This yields a four-part drama: Israel’s story, Christendom, modern decline, and an emerging global-humanist Anthropocene. The gospel is always contextual, shifting with history. The church must rediscover its priestly role amid cultural, technological, and ecological upheavals, fostering resilience, wisdom, and integrity. Missional communities should embody tradition dynamically, engaging history while adapting to present crises and future transformations.

We are probably stuck with the distinction between “church” and “mission.” I attend a church in Westbourne Grove. I work informally with a mission organisation. But in biblical terms there is something odd about our obsession with mission. The word occurs only four times in the ESV, in a mostly trivial sense. The one New Testament example is 2 Corinthians 11:12, where Paul speaks of the “boasted mission” of his opponents, but there is no word for “mission” in the Greek; the “false apostles” merely “boast.”

In this attempt to outline a revised “missional theology” for a short course, I would rather distinguish between the normal life and work of the people of God in history and how that people seizes a positive opportunity at an abnormal time of crisis or transition.

Simply put, there is action and there is reaction. Action is the core priestly function of the church under settled conditions—embodiment, representation, mediation, provocation, etc. Reaction is the response to disruption—prophecy, proclamation, reformation, judgment, deliverance. In the Old Testament, it is roughly the distinction between the Law and the Prophets. In the New Testament, we have only reaction to a crisis. Normal priestly action under settled conditions is deferred to the age-to-come.

The sending of a small number of disciples into the world to make disciples of the nations in the run up to the coming of the kingdom of God within a generation was a circumstantial reaction at a time of crisis.

We can call that a “mission,” even if the ESV doesn’t. But if we talk in general terms about the mission of the church or reduce mission to personal evangelism or some other programme, we immediately lose sight of the contextual dynamic that shapes action throughout the Bible.

So here I will sketch a contextually dynamic missiology that will take us all the way through to our current nostalgia for a lost Christian civilisation and the innocent questing of Gen Z.

1. A narrative-historical missiology

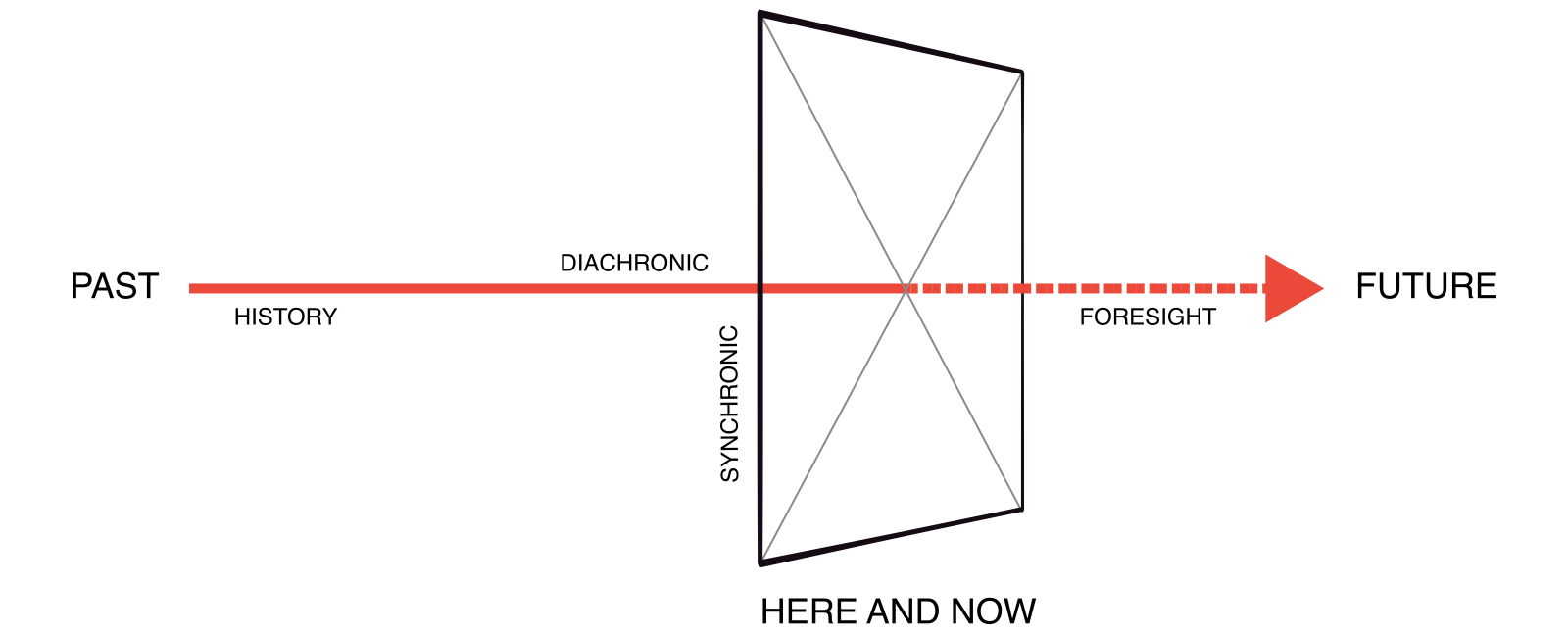

The present moment can always be described according to two axes. This is a basic piece of hermeneutical intersectionality, I suppose.

The synchronic axis is really the plane of everything that is here and now—the scintillating field of the relationships, communications, and experiences that make up human existence. It is thicker than a snapshot, more like a “Live Photo” or a TikTok video, but still only a brief period of recall and anticipation in time.

The diachronic axis runs through time. It is the axis of history, the story of how we arrived at the present moment, and it typically has enough narrative momentum to expose likely futures, or at least the beginnings of likely futures. We have some sense of what may come next.

The modern church largely lives in the here and now because it has inherited a transcendent, universalised theology that has nothing to say about history except that incarnation and redemption happened two thousand years ago, smack in the middle of cosmic time.

The church, therefore, collapses the Bible to serve the three-dimensional present moment: relationships with God, within the church, and with the world around us. Theological paradigms (trinitarian, incarnational, liberationist, salvationist, social) dominate. We have little time for the exile except as a type of redemption; we have little time for eschatology beyond the personal hope of eternal life.

The Bible, however, is a thoroughly historical document, in two respects: first, it is the product of history and bears the scars of history; secondly, it tells a densely interwoven story that runs through history, from the calling of Abraham out of the shadow of Babel to the defeat of Babylon the great, which was pagan, imperial Rome.

Much of the story is told retrospectively, historiographically—though ancient religious historiography is not a straightforward thing. But there is also a critical prophetic or apocalyptic aspect to the storytelling. Why? Because from time to time the community telling the story arrives at a crisis, an impasse, and is anxious to know what lies ahead. It is of the essence of Israel’s understanding of God that he takes them from the past into the future.

Jesus belongs to this story about Israel and the nations, in the first place, not to the hollowed out, uneventful account of creation and fall, incarnation and redemption, and new creation, that mostly shapes our preaching and teaching. He saved a historical people from a historical crisis because of historical sins.

But if we take biblical history seriously, we have to accept that history did not end with the resurrection or on the day of Pentecost. On the one hand, the New Testament presses into its own realistic future: the war against Rome, the conversion of the nations of the Greek-Roman world to the worship of one God and allegiance to one Lord. On the other, we are having to deal with momentous changes in our own time.

So we need a “hermeneutic” that encompasses the fullness of the historical experience of the people of God, and I now propose a tetralogy—a historical drama in four parts, each part having its own dramatic integrity.

It could, of course, be done differently. For example, we could talk about three act Hollywood films rather than five act Shakespearean plays. But the point is not to overweight the formative but limited biblical part of the narrative. We have our own stuff to deal with.

Part One: The story of Israel and the nations of the ancient world, climaxing in the prophetic expectation that the root of Jesse would rule over the peoples of the Roman Empire. We can break this down into five acts: i) acquisition of the land; ii) the kingdoms of Israel; iii) subjection to eastern powers; iv) subjection to western powers; v) apostolic mission to the nations of the Greek-Roman world.

Part Two: The concrete historical realisation of the prophetic hope articulated in Part One in the long history of western Christian civilisation, also known as Christendom.

Part Three: The impact of modernity and the long decline of western Christian civilisation—though now that it is gone, it has become fashionable to extol its virtues. Ayaan Hirsi Ali is just one remarkable voice among many: the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition “consists of an elaborate set of ideas and institutions designed to safeguard human life, freedom and dignity—from the nation state and the rule of law to the institutions of science, health and learning.”

Part Four: The dawn of a new and increasingly globalised order shaped by a progressive humanism, science and technology, a rebalancing of political and cultural power, and environmental degradation. What it means to be human is no longer given to us by the western tradition. Everything is up for revision.

What the work of the people of God looks like is contingent upon this shifting narrative frame, as the synchronic field slides along the diachronic axis:

- to embody, among the peoples of the Ancient Near East, the lively presence of the one God who made the heavens and the earth (action);

- to inherit the world not through Torah-observance but through suffering (reaction); and having achieved that, to direct and maintain a just, God-fearing civilisation (action);

- to survive the onslaught of modernity (reaction);

- in the first place, now, to work out how to be a gift to the world as we endure the birth pains of the age to come (reaction → action).

2. The ends of the ages

The “end of the age” is a familiar biblical trope. A historical hermeneutic allows us to apply it quite properly to the complex transformations that we are currently experiencing at all levels of society.

- We are seeing the end of western “colonialism” in its hard and soft forms, with the rise of China in particular, the globalisation of industry, services, and culture, and mass migration. It was the perceived disintegration of western civilisation in the face of political and religious authoritarianism that largely inspired Hirsi Ali’s conversion.

- Our basic anthropology, our understanding of what it means to be human, is being quite fundamentally revised, most notably these days with respect to sexuality. This, I think, is what the culture wars are mainly about.

- Our technological capabilities have been massively extended over the last two hundred years: rapid transportation, medical technologies, weapons of mass destruction, global communications, computing power and AI, etc.

- Humanity now imposes an intolerable burden on the planet, to the extent that we must reckon with what is likely to be a catastrophic epochal transition from the environmental stability of the Holocene to the instability of the Anthropocene, for which the only biblical antecedent is the flood.

Over this period the church has been on a dramatic downward learning curve. It has learned to survive by raising a conservative and sometimes fundamentalist bulwark against progressive forces, by renewing its inner life in the Spirit, by repositioning itself in the world, by mimicking its neighbours and competitors—and, I would add, by doing some very serious rethinking about what the Bible is saying. Perhaps in parts of the West the church has nearly learned enough.

3. But the good news is…

Like mission, the good news or “gospel” is contextual, contingent upon history. There is always good news to be proclaimed, but what it looks or sounds like depends on what the God of history is doing in the world.

So the good news of personal wholeness and well-being, which is at the heart of much modern preaching—at least, it’s what I heard at a church I visited last Sunday, when we were shut down because of the Notting Hill Carnival—is not necessarily mistaken. It may reflect some aspect of what God is doing in the world now. But it is not the same good news that we hear proclaimed in the New Testament.

The gospel in the New Testament is a quite different kettle of fish. In fact, it was two quite different kettles of fish.

First, it was good news that the God of Israel was finally about to act to judge and redeem his persistently unfaithful and recalcitrant people, through the agency of his Son.

Secondly, it was good news that the messianic agent of Israel’s salvation would sooner or later judge and rule over the nations of the Greek-Roman oikoumenē—the Roman Empire, in other words.

It may now be good news that we are belatedly rediscovering the Christian roots of western civilisation. Hirsi Ali again:

But we can’t fight off these formidable forces unless we can answer the question: what is it that unites us? The response that ‘God is dead!’ seems insufficient. So, too, does the attempt to find solace in ‘the rules-based liberal international order’. The only credible answer, I believe, lies in our desire to uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

But I think it will be better news in the long run that the church in the West is being slowly and chaotically re-formed to serve its priestly purpose in the next age-to-come.

None of this means that there is no gospel of reconciliation to the living God, by which people share in the life of the historical community for which Jesus died. It’s just that we ought to foreground the larger, prophetic narrative themes. Hirsi Ali needed a big, civilisation-level reason to align herself with the Christian tradition; she has bought into—and has become an actor in—a storyline that is much bigger than herself. That’s a thoroughly biblical conversion.

4. So what is the church for?

According to the biblical story, the people of God began with a summons into an effective being.

Israel existed as a “new creation” in the land, where it would be blessed, fruitful, prosperous. It functioned as a priesthood, serving the living God in the midst of Godless nations. That was the action, the basic work it had to do.

The crisis of imperial aggression compelled Israel to find a narrow path of suffering that would lead to a glorious new world, so the churches of the apostolic mission emerged as eschatological communities, bearing painful witness to the future reality. The figure of the suffering servant appeared first in the exilic period, then became Jesus, then became in effect the persecuted apostles and churches. This was all reaction.

When the nations finally abandoned their idols, turned to serve the living God, confessed Jesus Christ as their supreme Lord, the churches became a priestly caste for the Greek-Roman world, supplanting the ancient pagan priesthoods. That was their new action—to be a priesthood for a Christian civilisation.

The transition entailed the loss of the land, so the church now existed as new creation only in a derived or metaphorical sense. The church is only ever “new creation” when it is being made new, which is perhaps how things are right now.

In the modern era, the church has struggled to maintain the priestly function; it has become largely redundant, its rule usurped by new humanistic, pagan, and techno priesthoods. The focus instead has been on personal evangelism, revival, renewal—the reactive priority being to stop, and if possible reverse, numerical decline.

Towards the end of the modern era, the western church has become largely reconciled to its diminished and marginalised role. The challenge now is to redetermine a mode of priestly existence and action for the emerging Anthropocene.

5. The life and practice of missional communities

So, by “missional communities” what I really mean is communities that own the tradition which goes back through western Christendom, to the witness of the early believers, to Jesus himself, through the troubled history of ancient Israel, to Abraham, but which are now reacting—consciously or unconsciously—to the challenges of the ends of the ages.

Given what I’ve said so far, this will entail among other things:

- engaging with the full extent of both the diachronic axis and the synchronic plane; we need both history and a theology that understands its place in history;

- redefining what it means to be a dedicated priestly caste in the here and now;

- re-imagining the place of the church in the world;

- developing the sort of mobility needed to make the journey into the future ;

- fostering a realistic social resilience;

- reading the Bible historically because history is our problem, not hell;

- becoming well motivated, inquisitive, questioning, resourced and resourceful learning communities;

- acquiring an appropriate wisdom—a much undervalued attribute in the modern era;

- appreciating and engaging with the full fabric of the western Church—charisma, disciplines, art, liturgy, architecture, music;

- acquiring virtue, recovering integrity;

- shaping a viable anthropology for the age to come—see my book: End of Story? Same-Sex Relationships and the Narratives of Evangelical Mission;

- bearing concrete, visible witness to an authentic freedom from the technological, economic, cultural, political “principalities and powers,” whether good or evil, that are driving humanity forward.

6. Quiet revival?

The “Quite Revival,” as such, may prove to be only a flash in the pan. Maybe not. But it has at least drawn our attention to the fact that we are close to crossing a post-Christian watershed—the boundary between Part Three and Part Four of the tetralogy.

Hirsi Ali’s journey began under the Muslim Brotherhood in Kenya. She spent twenty years in the wilderness of radical atheism before embracing Christianity as both a personal and a civilisational solution.

Gen Z likewise have not had to disentangle themselves from a stifling and regressive Christianity as the last of the moderns had to—their parents and grandparents. They have not felt the irrelevance of the church. They have not had to deconstruct. So Gen Z seekers like Lamorna Ash give us a glimpse of what the future will look like.

Thank you so much for this, I just wish that I had written it!

You’ve clearly articulated issues that I’ve been groping towards for years, but which I’ve never quite managed to draw together. As my writing career is winding down, I’m so grateful to you.

Recent comments