My assumption has always been that we have a “higher” christology in the Gospel of John than we do in the Synoptic Gospels, but I’m beginning to have my doubts. I argued last week that when Jesus is accused by the Jews of making himself equal to God or making himself God (Jn. 5:17-18; 10:33), his response, in effect, is, “No, I am the Son of Man, authorised by God to speak and act on his behalf”, which is more or less the claim made about him in the Synoptic Gospels. But what about the saying “Before Abraham was, I am” in John 8:58? Isn’t that a barely disguised assertion of divine identity?

“I am” as the name of God

In his book The Only True God: Early Christian Monotheism in Its Jewish Context James McGrath notes the absolute “I am” statement in John 8:58. Not “I am the good shepherd” or “I am the light of the world”. Just “I am”.

This looks like an appropriation of the name “YHWH” as it was revealed to Moses: “I am the one who is” (egō eimi ho ōn). We would then have to assume that Jesus is “claiming to be none other than the God revealed in the Jewish Scriptures”—except that, as C.K. Barrett has pointed out, it is intolerable to think that John has Jesus say, “I am Yahweh, the God of the Old Testament, and as such I do exactly what I am told” (61).

Here’s the problem: a few verses earlier Jesus said, “then you will know that I am (egō eimi) and that I do nothing by myself, but as the Father taught me, such things I speak” (Jn. 8:28, my translation). This absolute “I am” statement is directly interpreted by Jesus himself to mean that he speaks and acts as an agent sent by God, not as God incarnate.

McGrath maintains that there are instances in Jewish writings of the period where an agent of YHWH, such as an angel, is given the divine name “in order to be empowered for his mission”. The example he provides is from the Apocalypse of Abraham, which dates from sometime between AD 70 and 150: Abraham’s heavenly guide is called Yahoel, which combines the two names for God “Yah” and “El”. Abraham hears God say to the angel: “Go, Yahoel of the same name, through the mediation of my ineffable name, consecrate this man for me and strengthen him against his trembling” (Apoc. Abr. 10:3; cf. 10:8). The angel consecrates Abraham by means of the divine name which has been given to him to bear as his own name.

Later Jesus will pray for his disciples: “Father, keep them in your name, which you have given me, that they may be one, even as we are one” (Jn. 17:11). So if “I am” is the name of Israel’s God, it has been given to Jesus as the supreme agent of God at this juncture in Israel’s history in order that he might carry out his mission. It means, in effect, that Jesus has been given the authority of God to act in this exceptional and controversial manner on God’s behalf.

McGrath says: “This was a way that, in this period of Jewish history, God was believed to honor and empower his agents, and it is a continuation and development of this idea that is found in John” (62).

The argument is a little different in Philippians 2:9-11, where Jesus is given “the name which is above every name” not in order to reveal YHWH to Israel but to rule over the nations.

I am the light of the world

This does not, however, explain the temporal statement: “Before Abraham was, I am.” McGrath doesn’t discuss this. Jesus does not merely claim to have been given the name of God; he has had that name—in some sense—from a time before Abraham.

To understand this, I think we first need to consider the whole “light of the world” discourse in John 8:12-9:41. The passage can be read as a reflection on the significance of Jesus in the light of the servant motif in Isaiah 40-55 and in Isaiah 43:8-13 LXX in particular:

And I have brought forth a blind people, and their eyes are likewise blind, and they are deaf, though they have ears! All the nations have gathered together, and rulers will be gathered from among them. Who will declare these things? Or who will declare to you the things that were from the beginning? Let them bring their witnesses, and let them be justified and speak truths. Be my witnesses; I too am a witness (kagō martus), says the Lord God, and the servant whom I have chosen so that you may know and believe and understand that I am (egō eimi).

Before me there was no other god, nor shall there be any after me. I am God, and besides me there is none who saves. I declared and saved; I reproached, and there was no stranger among you. You are my witnesses; I too am a witness (kagō martus), says the Lord God. Even from the beginning there is also no one who rescues from my hands; I will do it, and who will turn it back? (Is. 43:8–13; cf. 41:4; 45:18)

These seem to me to be the main points of correspondence:

- Israel is YHWH’s servant, “the offspring of Abraam, whom I have loved” (Is. 41:8 LXX). The righteous in Israel are told to “Look to Abraam your father and to Sarah who bore you; because he was but one, then I called him and blessed him and loved him and multiplied him” (Is. 51:2). Jesus says that the Jews are children not of Abraham but of the devil (Jn. 8:39-44).

- YHWH’s servant, Israel, is given “as a light to nations, to open the eyes of the blind”; he will bring “from the prison house those who sit in darkness” (Is. 42:6–7; cf. 49:6 LXX). The deliverance of blind and captive Israel will reveal to the nations the power and mercy of Israel’s God. Jesus asserts that he is the light of the world, sent by the Father. Those who follow him “will not walk in darkness” (Jn. 8:12). When he goes on to heal a man blind from birth, he says, “We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming, when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world” (Jn. 9:4–5).

- YHWH seeks witnesses to the fact that he has “brought forth a blind people, and their eyes are likewise blind, and they are deaf, though they have ears”: “Be my witnesses; I too am a witness, says the Lord God, and the servant whom I have chosen so that you may know and believe and understand that I am (egō eimi)” (Is. 43:8-10 LXX). In this discourse Jesus says, “I am (egō eimi) the one who bears witness about myself, and the Father who sent me bears witness about me” (Jn. 8:18).

- YHWH and his servant bear witness together to the fact that “I am”. “Before me there was no other god, nor shall there be any after me” (Is. 43:10). The Father and Jesus bear witness to Jesus’ claim “I am the light of the world”; and Jesus says, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am” (Jn. 8:58).

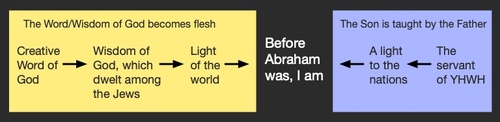

So the Jesus who says “Before Abraham was, I am” is identified, albeit somewhat loosely and without much sense of the prophetic-narrative framework, with the Isaianic servant, who will be a light to the nations. But the phrase “light of the world” also, of course, refers us back to the opening of John’s Gospel.

The true light was coming into the world

In the Prologue the light that has come into the world is equated with the word or wisdom of God, which “became flesh and dwelt among us”. This appears to play on a quite well established Wisdom trope, which we find stated positively in Ben Sirach and negatively in the Similitudes of Enoch:

Then the creator of all commanded me, and he who created me put down my tent and said, ‘Encamp (kataskēnōson) in Jacob, and in Israel let your inheritance be.’ Before the age, from the beginning, he created me, and until the age I will never fail. In a holy tent I ministered before him, and thus in Sion I was firmly set. In a beloved city as well he put me down, and in Jerusalem was my authority. And I took root among a glorified people, in the portion of the Lord is my inheritance. (Sir. 24:8–12)

Wisdom found no place where she might dwell; Then a dwelling-place was assigned her in the heavens Wisdom went forth to make her dwelling among the children of men, And found no dwelling-place: Wisdom returned to her place, And took her seat among the angels. (1 En. 42:1–2)

So it may be said that the Wisdom or Word of God should have found a place in Israel and in Jerusalem as the light of the world but was unable to do so. Israel failed in its mission. John’s claim is that the personified Wisdom of God has now become flesh in Jesus as the light of the world and not in Israel—indeed, his own people rejected the true light when it sought to live among them (Jn. 1:11).

So now Jesus is the true Isaianic servant, embodying the light of the world, which is the Wisdom and Word of the creator God, who does the works of the Father, who says what he has been taught by the Father (Jn. 8:28; cf. 8:26), who opens the eyes of the blind, rescues people from darkness, and is the source of the life of the age to come.

According to the Jewish Wisdom trope, the Word took the initiative, becoming flesh. But according to Jesus’ teaching, it is because he has been taught by the Father that he can legitimately claim to be the light of the world and is, therefore, the Wisdom and Word of God. He bears witness to himself, admittedly, but this testimony is backed up by the marvellous works that he does, such as opening the eyes of the blind man, which constitute the witness of the Father.

“I am” not as the name of God

In addition to the absolute “I am” statements that find we in John 8:24, 28, 58 there are two other types of “I am” statement in the Gospel.

- There are normal predicative statements, which say something about the first person speaker: “I am the bread of life…, which comes down from heaven” (6:35, 41, 48, 51); “I am the light of the world” (8:12); “I am the one bearing witness about myself” (8:18); “I am from above… I am not from this world” (8:23, 24); “I am the door of the sheep” (10:7, 9); “I am the good shepherd” (10:11, 14); “I am the resurrection and the life” (11:25); “I am the way and the truth and the life” (14:6); “I am the true vine” (15:1, 5).

- There are “I am he” type statements, which serve to identify the speaker: “I am, the one speaking to you” (4:25); “I am; do not be afraid” (6:19); Jesus asks Judas and the soldiers whom they seek and responds, “I am” (18:5, 6, 8). The usage is found in the Synoptic Gospels: when the disciples think they have seen a ghost, Jesus reassures them: “Take heart. I am. Do not be afraid” (Matt. 14:27). It also seems fairly common in the Septuagint. For example, Gideon asks an angel of the Lord to wait while he gets something to sacrifice, and the angel says, “I am (egō eimi); I will stay seated until you return” (Jdg. 6:17–18; cf. Ruth 4:4; 2 Sam. 11:5; 13:28; 20:17; 2 Kgs. 4:13 LXX).

God is revealed to Moses as “I am the one who is” for the first time at the burning bush. So we should perhaps assume that when Jesus says, “Before Abraham was, I am”, this is not so much a reference to the revealed identity of YHWH as a more general affirmation of personal significance, in keeping with the second usage, in the context of the complex chain of symbolic identifications that underpins the “light of the world” discourse. He is the obedient servant, taught by the Father; he is the light of the world, which is the true light rejected by Israel, which is the Wisdom of God, which is the Word of God.

The divine “I am” statements of Isaiah 40-55 are arguably of the same type—less a reference to Exodus 3:14 than an affirmation of divine significance in the particular context. For example: “Who has performed and done this, calling the generations from the beginning? I, the LORD, the first, and with the last; I am (egō eimi)” (Is. 41:4; cf. 43:10; 43:25; 46:4; 51:12).

In conclusion

This has been a difficult line of enquiry. I’ll try to draw some basic conclusions, and we’ll see where it leaves us:

- The “Before Abraham was, I am” saying is part of John’s searing indictment of the Jews, who have failed to fulfil their calling to be the servant of YHWH, a light to the nations.

- Instead, Jesus is the authentic servant of YHWH, the light of the world, because he has been taught by the Father and does the works of the Father, with the authority of the Father. The works that he does are from God and therefore bear witness to the truth of the claims that he makes about himself.

- McGrath may be right to suggest that “I am” is the name which God gave to Jesus as the agent of his purposes. But I think that “I am” may function primarily as an affirmation of personal significance within the particular context of the “light of the world” discourse.

- John’s semi-fictitious Jesus declares, “Before Abraham was, I am”, because Isaiah’s “light to the nations” has been reconceived as the light which is the pre-existing Wisdom or Word of God, which became flesh and dwelt among the Jews.

It is very important to try an exegesis from the Jewish view (story) to interprete John better than from an Graeco-romaneous view of the later church fathers… thank you for this zeal to get it that direction. At least it shows, that there are alternatives which could interprete it much better.

I am thrilled to see every time the important storyline from the Jesaja 40-60… recovered in the Jesus-words (like: Light of the world…).

Thanx Andrew.

@Helge seekamp:

That’s nice. I share your enthusiasm for Isaiah 40-66.

This review by Wayne Coppins of a recent book by Jorg Frei may have some input for you.

https://germanforneutestamentler.com/2018/11/26/jorg-frey-t…

I think John is far less complicated than you make him out to be.

In the first place, “the Jews” understood perfectly what Jesus was claiming in John 8. The only capital offence for which they could take the law into their own hands was blasphemy, and this they are about to do in 8:59. This was a Jewish reaction based on Jewish, not Greek, perception.

In John1, it’s not simply that God’s wisdom became enfleshed in Jesus, but the Logos, the choice of which word requires explanation in itself, “was with God, and the Logos was God”. The identification with God is total. Not only so, but the world was created through Jesus the Logos. In Jesus, the creator is entering and becoming part of his creation . This sets the scene for the entirety of John’s gospel. The rest of John 1 confirms this extraordinary development in the history of God. Even the Jehovah’s Witnesses have to concede that if Jesus was not God, he was somewhere between God and man: a god, in effect. I’ve yet to see where you put him.

If in John 5, making himself “equal with God” does not mean “the same as”, then how can a “son” be equal with a “father”, in your view? If, as you insist, the son was a human agent subordinate to God, why do you think the Jews say he is claiming equality with God? The simplest explanation is the best: they think he is blaspheming, for which they would have the right to kill him.

In John 10, the claims Jesus was making about himself as the Jews (not later Greeks) understand it are given the clearest possible explanation. “We are not stoning you for any of these (miracles),” replied the Jews, “but for blasphemy, because you, a mere man, claim to be God.”

Nothing could be clearer, and given the perfect opportunity to set things straight, Jesus blows it with a cryptic reply for which the only logical explanation (there are some illogical ones) is that the Jews weren’t wrong.

To go back to John 8, there may indeed be some interesting examples of the usage of “I am” across the gospels, where identification with the divine name is not assumed. But here, the reaction of the Jews makes it plain: they thought he was blaspheming, for which they had the right to stone him, granted by the Romans, there and then.

@peter wilkinson:

Well, yes, it’s far less complicated if you ignore all the details.

@Andrew Perriman:

Maybe I could put it in terms of some questions, which have as their assumption that we should always look at the meaning of what Jesus says in its primary context. In the following, I am simply running through your text and asking questions at each point. The result may seem repetitive, but it is following closely the sequence of your own sequence.

I’ve already asked a question and raised doubts about your interpretation of John 5:17-18 and John 10:33.

I haven’t read James McGrath, but might ask the following:

Why is it really “intolerable” (C.K. Barrett’s protest) if Jesus, being one with the Father, nevertheless placed himself in voluntary submission to the Father, and says “I speak exactly what the Father has told me to say” — John 5:19?

Why is it really intolerable that Jesus is redefining YHWH by the Father/son relationship?

If John 5:19 (and John 8:28) both say that Jesus only speaks the Father’s words, does this mean he is only an agent? Why can it not mean an inseperable relationship?

Why should “God incarnate” (as the son) not speak only the words of God (the father), if the one places himself in voluntary surrender to the other?

Is the “absolute “I am” statement really “directly interpreted by Jesus himself to mean he speaks and acts as an agent sent by God and not as God incarnate”? Why should it mean anything other than “God incarnate”, if the consistent self-centredness of what Jesus says, and his equally consistent failure to deflect attention from himself to “God” suggests that he was indeed, or intended to be thought of as “God incarnate”?

Is the passage from the Apocalypse of Abraham actually saying that when Yahoel is to go “through the mediation of my ineffable name” it means something more than that the name of an angel bears witness to his divine mandate, or even simply that the angel is commissioned by God? Why should it mean more than that?

Is the consecration of Abraham “by means of the divine name which God has given to him to bear as his own name” McGrath’s interpretation, your own, or clearly what the Apocalypse says?

If the divine name is “I am”, then isn’t there a difference between the giving of the divine name to Jesus in John 17:11 — “the name you gave to me”, and “Yahoel”, which in itself wasn’t the divine name?

Has McGrath actually demonstrated that “This was a way that, in this period of Jewish history, God was believed to honor and empower his agents”? From what you say, he hasn’t done that with the angel.

Isn’t the point of John 8:18 that instead of bearing witness to the deliverance of Israel by YHWH, to which Isaiah refers in 43:8-13 as supremely and only YHWH’s deliverance alone, Jesus says: “I am the one who testifies for myself, my other witness is the one who sent me - the Father”? The connection with the servant in Isaiah highlights the fact that what was said exclusively of YHWH in Isaiah:43:8-13 especially is now echoed by Jesus speaking exclusively of himself. This is either blasphemy, or Jesus was part of a divine Father/son relationship.

I simply don’t get how you demonstrate from your analysis of the servant in Isaiah that “Before Abraham was, I am” says anything other than that Jesus preceded and prexisted Abraham, and the “I am” is shown to be a blasphemous claim by the reaction of the Jews. (I’m running out of the ability to ask questions).

If Jesus was the embodiment of the wisdom described in Sirach and Enoch, then what are we to make of the form in which John 1 says that wisdom came? You omit to mention that the first verse of John says “He (the Logos) was “with God and the Logos was God”.

Isn’t the significance of Jesus’s “I am” statement in 8:58 made clear by the reaction of the Jews? (“At this they picked up stones to stone him”).

Isn’t the significance of the seven “I am” statements in John’s gospel in the attributes which the verbs introduce, which might be thought to be attributes of God rather than an agent, particularly when you see how John develops them in the associated discourses?

There is no explicit connection between “light” and “wisdom” in the extracts from Sirach and Enoch you have quoted, and no mention of “light” at all. But that’s not to say “light” was not associated with wisdom at all. Rather, the particular origin of the “light” idea goes back to the first creation narrative.

The association of “light” in John 1 is very strongly with Genesis 1:3, and John is clearly modelling John 1 on the opening verses of Genesis 1. The meaning of this points to Jesus as not simply the bearer or embodiment of wisdom (which he was!), but also as the bearer of the new creation, which is of course the framework John 1 provides for the whole gospel.

In other words, Jesus is not simply echoing the prevailing wisdom idea, such as in Proverbs 8, but taking it further, to make wisdom, or the Logos, God himself, “In the beginning … the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God”. Jesus appears as the Logos. The creator enters his creation, and becomes joined with it.

Which brings us back to the confrontations with the Jews in John 5:18, John 8:56 and John 10:33, in which not only does the reaction of the Jews make very clear that Jesus was claiming not simply God’s activities but God’s own person for himself, but the surrounding context fails to remove, and rather reinforces the idea that Jesus was treading on territory that belonged only to God himself, without correction or qualification.

I didn’t make the last response to your post a question, as I thought it was getting rather overworn.

Even though the author of the 4th Gospel used metaphors like light and logos, I believe he was intentionally portraying Jesus as a human who preexisted as a heavenly being—the begotten son of Yahweh. Jesus came from heaven and returned to heaven. I think you could call his view “binitarian” and according to scholars like Boyarin and Heiser, this view was not that unusual in first-century Judaism since they already had an understanding of two powers in heaven. This would explain why Christianity was able to exist within Judaism for a couple of centuries before being pushed out by Jews and pulled out by Gentiles.

The phrase could simply mean “I am the Christ”.

The first I am statement in John implies this in 4:25. The book is written that all may know he is the Christ.

Since Jesus typically attempts to silence those declaring he is the Christ before his crucifiction, John would certainly have a higher Christology since Jesus explicitly states he is the Christ — but John’s narrative is not unique (i.e. does make higher/greater claims about Jesus).

@Chris:

Chris, I think there’s a lot to be said for this. The question of the identity of the Christ is a major theme in the Gospel (cf. Jn. 1:20, 25, 41; 3:28; 4:26, 29; 7:26, 31, 41-42; 9:22; 10:24; 11:27; 12:34; 20:31). The difficulty is finding this question in the “light of the world” discourse, where it seems to me that the “I am” statements of God in Isaiah are more relevant (Is. 41:4; 43:10, 25; 45:8, 18-19, 22; 46:9; 48:12, 17; 51:12; 52:6).

The connection between Isaiah 52:6 and John 4:25-26 is interesting:

Therefore my people shall know my name in that day, because I myself am the one who speaks (egō eimi autos ho lalōn): I am here (Is. 52:6)

The woman said to him, “I know that Messiah is coming (he who is called Christ). When he comes, he will tell us all things.” Jesus said to her, “I who speak to you am he (egō eimi, ho lalōn soi).” (Jn. 4:25–26)

Recent comments