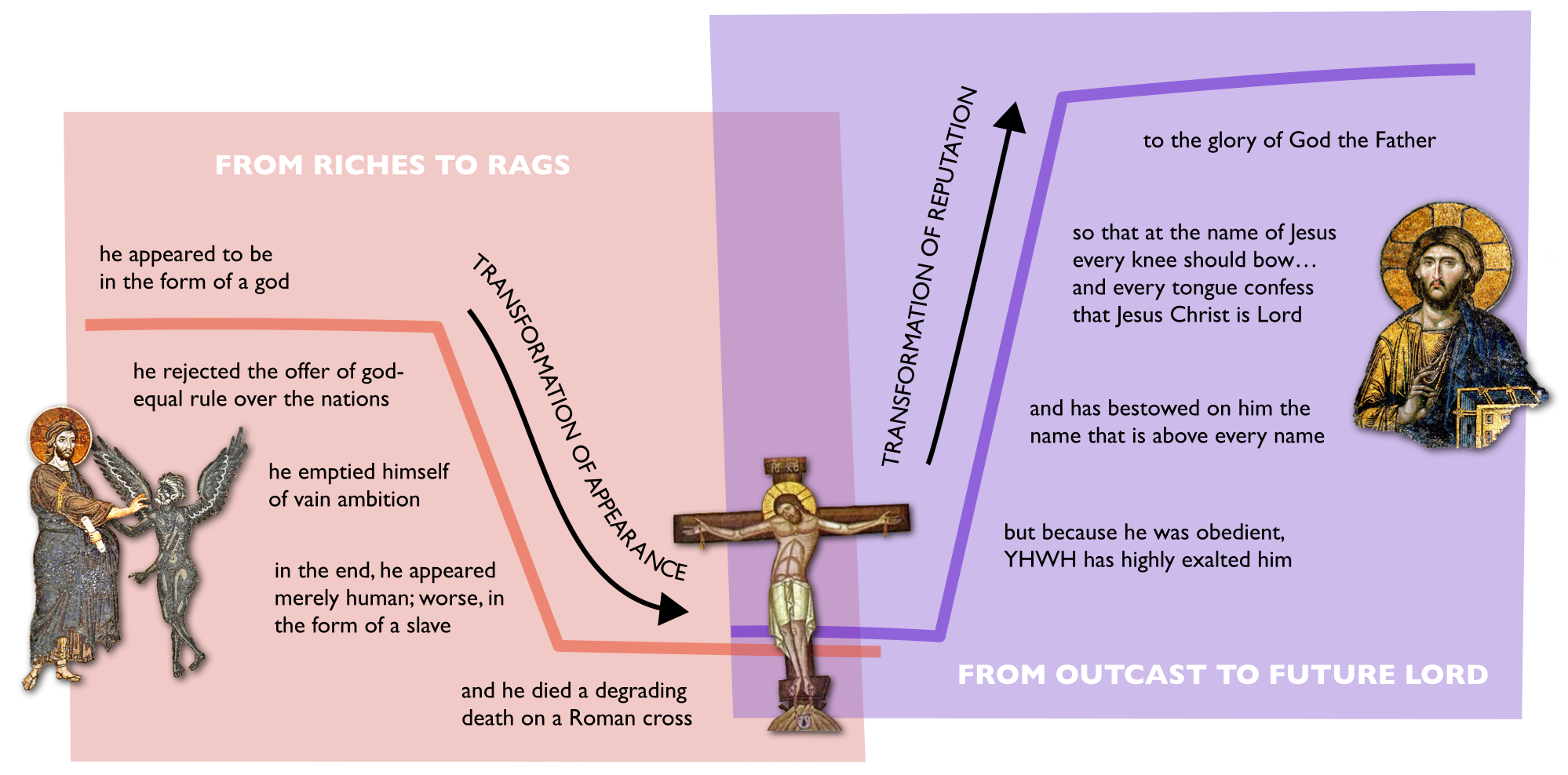

It is easy to visualise the traditional interpretation of Philippians 2:6-11 as a downward parabola or u-bend: Christ existed in heaven from eternity “in the form of God”; he descended into the world, becoming man and dying on the cross; then he is raised from the dead and restored to his position in heaven. Here again is that “cosmograph” for the who missed it the first time round.

My argument in In the Form of a God: The Pre-existence of the Exalted Christ in Paul is that what the encomium plots is not a cosmic journey or metaphysical transformations but changes in the estimation in which Jesus was held, how he was perceived, particularly with reference to how the story might have been understood when told to pagan Greeks in the context of the Pauline mission in Asia Minor and around the Aegean.

Helge Seekamp suggested that it might be worth having a second graphic to illustrate this reading, so I thought I’d give it a try. We still have a u-bend, of course, but what comes down and goes up is not the person of Jesus but his reputation, his approval rating: he is applauded at first, then booed and hissed at, but will eventually be given a standing ovation. Click for a larger view.

The Byzantine mosaics make two points: first, that this was a story being told to the Greek world about the Greek world; secondly, that appearances mattered (cf. Is. 52:13-53:3).

What follows is a paraphrase which aims to bring out something of the rhetorical force of what I suspect is a highly condensed summary of a more elaborate reflection on the significance of the Jewish Jesus for the Greek world.

From riches to rags

The first part of the encomium tracks what is essentially a Greek reappraisal of the career of Jesus.

He appeared initially as a wonder-worker, a thaumaturge, a divine man, in the form of a god, set apart and empowered with a heavenly presence at his baptism.

He rejected the opportunity presented to him to attain god-equal, Caesar-like rule over the nations of the Greek-Roman world—in language, incidentally, that implicitly invoked the Shema, the agreement to serve one God in the land which God gave to Israel: “You shall worship the Lord your God, and him only shall you serve” (Lk. 4:8; cf. Deut. 6:4, 13).

Instead, he emptied himself of “vain ambition” (cf. Phil. 2:3) through the severe asceticism of the wilderness experience, and took on the quite contrary outward appearance of a slave. To the Greek mind, he squandered the reputation and potential that he formerly had as a godlike figure—or in Satan’s more orthodox terms, a “son of God.”

It was now apparent to any onlooker that there was nothing remotely divine about this person. Quite the opposite. His fanatical obedience to a desperate vocation led only to a degrading death on a Roman cross. There is no atonement here, only wretchedness.

From outcast to future Lord

In the second half of the encomium we shift from the language of Greek appraisal to the language of the Psalms and Isaiah.

In the eyes of the Greeks, the career of Jesus was a disturbing riches to rags story (cf. 2 Cor. 8:9, another supposed pre-existence passage which I discuss in the book). It started well but ended badly—a Hellenistic romantic storyline thrown violently off course by a perverse, self-destructive loyalty.

But in the estimation of the God of Israel, Jesus had remained faithful to his calling, and for that reason God massively raised his profile in the ancient world.

Paul undoubtedly believed that Jesus was now actually seated in heaven at the right hand of the Father (cf. 1 Cor. 15:25-27), but that is not what he is saying in this encomium in praise of Jesus Christ.

He means rather that God has given the man who lost everything in life a new exalted status, above all other beings in the cosmos. He has graciously bestowed upon him a name which is above every name—a renown above all renown, a reputation that will reach from east to west—so that it will be at the name of Jesus, in recognition of his transformed status, that people will bow the knee and confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of the God the Father.

In other words, the encomium is a prophetic celebration of the agency by which the peoples of the Greek-Roman world would eventually be converted to worship of the God of Israel.

This is very helpful. I read the book and enjoyed it but felt like I couldn’t engage with it at the deeper academic and technical levels. This post helped pull it all together.

Thanks, Kevin. Maybe I should do something similar with the other passages.

Thanks, Andrew; this is helpful.

I have the book but have not progressed very far into it.

Perhaps this is answered in the book; forgive me for troubling you with it here if it is, though perhaps the question will occur to other readers who don’t yet have the book.

Both 2 Cor 8:9 and the Phil 2 encomium are not free-standing Christological assertions; they support an argument Paul makes about how he wants his readers/hearers to live or something specific he wants them to do.

Does your proposed understanding of the meaning of these texts significantly revise one’s understanding of what Paul wants his readers to in terms of their “imitation of Christ”? Would it revise present application of these texts to “the Christian life”?

At the very least, I suppose that it makes imitation a bit less daunting.

@Samuel Conner:

Yes, with both those passages there are implications for how the imitation of Christ was understood, though I think in some ways the matter becomes more rather than less daunting.

In the “being rich, became poor” theme the contrast is straightforwardly between what we might call a “spiritual” abundance and a faithful self-impoverishment and affliction in other respects. What is said about Jesus is no different in principle—perhaps in degree—to what is said about the churches in Macedonia (2 Cor. 8:1-2) or Smyrna (Rev. 2:8-11).

This parallels the contrast in Philippians 2:6-8 between “being in the form of a god” and taking “the form of a slave,” though the rhetoric has shifted—another way of saying “being rich, he became poor.” But more importantly, I think that my reading solves the long-standing problem of why Paul uses christology to address an ethical concern (Phil. 2:1-4). At the heart of the story told in Philippians 2:6-8 is the disciplined—even ascetic—renunciation of “selfish ambition” (eritheia) and “vainglory” (kenodoxia). What the encomium celebrates is not metaphysical transformations but changes of standing and reputation—so yes, easier in the sense that it is within the reach of the Philippian believers, but it is still a renunciation potentially to the point of death.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thank you, Andrew.

I’ve been impressed for a very long time with Paul’s “one another” emphasis. It looks like I need to add to that a “let us suffer with the Messiah now, in order that we may later reign with him” emphasis.

There seems to me to be a great deal of grasping at overt power on my side of the pond. Perhaps we should be lowering our sights.

Both emphases seem highly relevant to the present life of the churches.

Again, thank you!

@Samuel Conner:

Yes, both emphases remain relevant, but I think Paul had in mind the specific role of Christ-like—Christ-imitating—communities, headed by the suffering apostles (“be imitators of me as I am of Christ”, which would be instrumental in bringing about, or at least which would herald, the coming rule of Christ over the nations. In other words, for Paul suffering had a very sharply defined eschatological function. We do not understand Paul better by generalising that function, even if the attributes gain traction in other contexts.

I am delighted about reding your instructive book „ in the form of a God“…

- it was very well argumented

- very much insight in the different interpretations of the scolars

- for me very plausible in reflecting the scientific hypthesis and their limits

- I believe, it was a hard effort to reach the goal, but it was worth it.

yes, it totally changes the picture from an unpolitcal redeemer-mythology to an very sharp focused political and historical fokused real „good message“. I am convinced and will try to share the news :-)

Thank you, Helge!

@Andrew Perriman:

Hi Andrew,

I thought it might interest you to learn that David Bentley Hart has had a second edition of his New Testament published, and, I’ve been told that he renders Phil. 2:5-8 this way:

“Be of that disposition in yourselves that was also in the Anointed One Jesus, who, subsisting in a god’s form, did not deem existing in the manner of a god a thing to be grasped, but instead emptied himself, taking a slaves form, coming to be in the likeness of human beings; and, being found in appearance as a human being, he reduced himself, becoming obedient all the way to death, and a death by a cross.”

It looks like “form of a god” is gaining steam:-)

~Sean

Well I never! But: 1) “subsisting” makes it too abstract; my argument is that Greeks would have thought quite concretely of the miracle-working Jesus as “in the form of a god”—a god-like person or divine man; and 2) “did not deem existing in the manner of a god a thing to be grasped” does not capture the narrative point: Jesus turned down the opportunity (presented to him by Satan) to rule over the peoples of the empire.

Hart gets the point about morphē presumably, but it looks as though he thinks it necessary to retain the idea of pre-existence: subsistence in heaven in god-form before some sort of ontological self-emptying.

Hart’s language over-theologises the piece. I think the language of Philippians 2:6-8 is much more earthy, the language of Greek popular story-telling.

@Andrew Perriman:

Well, asking a theologian not to theologize is like asking a tiger to change its stripes!

As for preexistence, I think that’s clearly implied in the text. One wouldn’t expect a man who never preexisted to be spoken of as, “found in appearance as a man” or as one who, “found himself in fashion as a man.”

A similar point has been made about why we should accept that Psalm 82 is referring to the Divine Council of heavenly gods and not human judges, namely, it’s unnatural to tell men that they will die like men. Since telling men that they will die like men is rather unnatural (as though some other option were on the table), it is likewise unnatural to speak of a man as being found or finding himself in fashion as a man.

As for preexistence, I think that’s clearly implied in the text. One wouldn’t expect a man who never preexisted to be spoken of as, “found in appearance as a man” or as one who, “found himself in fashion as a man.”

What I argue in the book is that the shift here is not between a pre-existent heavenly state and an earthly state but between the perception that he was in the form of a god, in appearance godlike (empowered by the Spirit, working miracles, speaking with extraordinary wisdom) and the realisation (“he was found”) that he was merely human, mortal, in fact a degraded human, a slave in appearance, who was killed on a Roman cross.

We have a parallel in the story of Paul and Barnabas at Lystra in Acts 14:8-23: they are acclaimed as gods by the Greeks, they reject the pagan evaluation, and they end up being stoned by the Jews and left for dead. The people of Lystra would have realised that these men were not gods after all, just mere mortals.

The story is told from a Greek point of view. This accounts very well both for the use of morphē, which must reference external appearance, and the harpagmos clause, which connotes an opportunity presented to attain not just the form of a god but the status of a god—implicitly as a divine ruler. I think this alludes to the opportunity presented to Jesus by Satan in the wilderness to rule over the nations of the empire, which Jesus refused to seize.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hi Andrew,

This above, IMO, is a nice succinct summary of your position… thumbs up. I’m still ploughing through your book and finding it really enlightening.

Recent comments